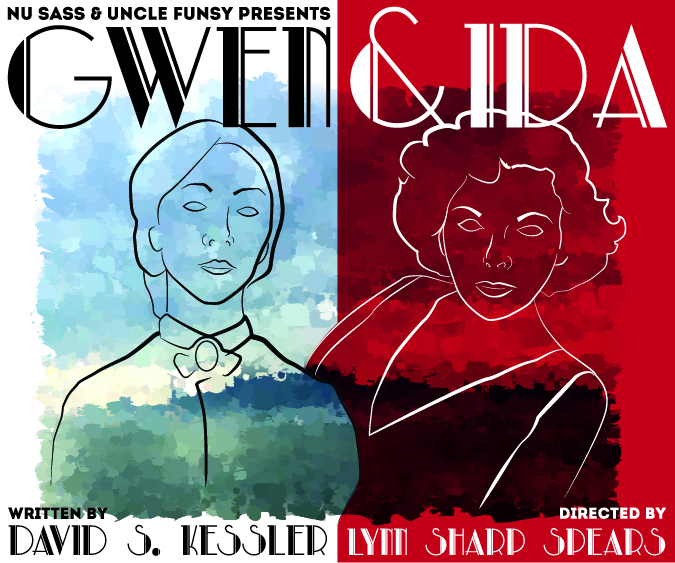

If you won’t tell your story, then who will? More importantly, will they tell it correctly? Or will they romanticize it through the lens of B-grade Hollywood celluloid and be creative with your very existence? Such might have been the ill-fated path of infamy for Gwen John if Ida Lupino had had her way when it came to telling her story on the big screen. Only it didn’t happen; Ida Lupino never made that film all about the life of Gwen John, and those two determined, headstrong, and stubborn women working in industries dominated by men were nearly lost to history save for a few esoterically invested interests here and there. They are not great name known to the common ear— not like Vincent Van Gogh or Jack Warner. They couldn’t or didn’t tell their stories; or maybe they did but no one is listening. Nu Sass Productions and Uncle Funsy Productions have come together for this world premiere of Gwen & Ida: The Object is of No Importance, written by David S. Kessler. Directed by Lynn Sharp Spears, this compelling 90-minute dramatic exploration uncovers fascinating details of larger than life, determined women who were perpetually engaged in the melee of a male-dominated industry. How prescient such a piece feels in our current political climate; how potent and important it is to experience such a piece of theatrical engagement, reminding us how women’s voices carry weight and importance.

There is minimal setting to speak of in the gallery-turned-performance space in the upstairs showroom of Caos on F. Bridgid Burge, providing set, props, and costumes, lets the story and the actors speak largely for themselves, fully embracing the well-tested notion that less is more, particularly in the intimate spacing of the venue. A tasteful movie poster of the time, a clutter desk of a bigwig movie executive, and a striking scrim meant to represent a painting (done divinely by Lynn Sharp Spears) comprises the set. A dashing fitted newsroom style executive brown women’s skirt suit for Ida and a more reserved cobalt dress and white lacy collar is fitted for Gwen, delineating the difference in their timelines. Burge designs with simplicity in mind, enhancing the audiences’ overall engagement with the text and the characters.

Complimenting Burge’s work are the lighting designs f Helen Garcia-Alton and the sound designs of Charles Lasky, though the latter are used so infrequently, they almost feel absent. While Lasky’s use of sound effects are few, far-between, and exacting (not to mention pristine accents of the scene work unfolding overtop of them), they cry out to be more thoroughly experienced, perhaps by way of including more of them. Garcia-Alton’s lighting is superb in the trying confines of the art gallery space, particularly when it comes to shifting from live-time existence to a moment of memory or recollection. The breath-taking visual created by Garcia-Alton’s interpretation of stained glass inside a convent is the perfect aesthetic enhancement to that scene.

David S. Kessler’s work with the script is intriguing. Though there are times when the overt and repetitive nature of the feministic drive smack a bit of overkill (then again, more than 100 years has passed since the prime of Gwen John’s life and women are still marginalized in art and film…), ultimately the script is succinct and unique in its message and subsequent delivery thereof. There are also moments where some of the dialogue has the feel of a mediocre B-grade Hollywood film, but because this occurs infrequently and at odd places throughout the performance it is difficult to tell if this was Kessler’s intention for either homage or send-up to the genre or merely places where the brilliance of his concept was too radiant for less clunky phrasing. The work is strong; the characters are extensively fleshed out, and ultimately the theatrical experience is an engaging if not informationally nurturing one. It is also slightly unclear as to whether or not this play has groundings in wild fantasy or magical reality because of the way Gwen is introduced and continues to exist and interact with the Jack character; but the muddled lines of whether or not she is really happening verses being a hallucination, ghost, or fictional construct matter less and less as the production progresses.

Director Lynn Sharp Spears spins brilliance into the pacing of the production. To quote Kessler’s work, “Artists are sometimes unware of the impact of their art.” Spears’ lasting impact of this production is profound, putting the truth and honesty of both character and narrative at the forefront of the experience. Spears pushes tension-driven moments of the production right to the precipice, to the fulcrum, to the very boundary of their exploding point and stops, letting the anticipation drive the audience’s maddening descent into sheer bewildering theatrical ecstasy. Honing in on these strikingly crafted moments in a way that gives them genuine depth and earnest, Spears creates a stunning narrative all her own with this script. One such moment that is burned into the mind is the anticipatory pause right at the zenith of conflict when Gwen states, “If you don’t tell your story, I will.”

In a story about powerful women that have all but been lost to history, it would be easy to dismiss the lone male character as cheap, comedic relief. And while the Jack character does provide some humorous moments, Matty Griffiths’ approach to Jack reminds the audience of the ugliness that women in the film industry faced at the time. Channeling the epitome of the brash, crass, and all-round jerk that the golden era of Hollywood produced limitlessly when it came to men in power, Griffiths makes the Jack character easy to dislike. (This makes the special lighting that befalls his character that much funnier. Though this plays into the larger problematic issue of whether the play is set in an actual reality, some magical reality, or dabbles across the blurry lines of both.) With a look that could be Jack Warner’s stunt double, Griffiths fits the bill in speech, vocal expression, and physical expression when it comes to being an exacting representative of everything wrong with powerful men from Hollywood’s golden era.

Gwen (Aubri O’Connor) and Ida (Rebecca Ellis) could not be more different and yet are very much the same. Rebecca Ellis launches the play into motion in a lengthy but clip-paced monologue that starts as a direct-address to the audience and quickly turns into a heated, yet mildly tempered debate with the Jack character. It is astonishing how her physicality, her facial expressions, her cadence and patois fit a ‘willful’ woman of the times. Ellis possesses a slow, smoldering burn underneath her character’s exterior, driving her and pushing her into these headstrong moments against both Jack and Gwen. There is a striking conviviality about the way she slips and slides in and out of moments of Gwen’s memory as well, where one moment Ellis is the absorbent ear of Ida and the next a living memory being recreated as someone significant in Gwen’s life.

Aubri O’Connor delivers breathless bouts of ecstasy throughout her performance as Gwen. Exploring the virulent soul of an artist, of a muse, of a woman, O’Connor’s mercurial episodes of mania and depression swing almost violently and often unexpectedly from one to the other, chasing words out of her mouth as if they were belched of fire up from her heart and out of her head. O’Connor explores the vast complexities and eccentricities of this volatilely unstable character that Kessler has penned as the charging force in this story. In one breath she is raving about not being a perfectionist but on her next exhale there is a deeply ingrained need for her work to be perfect. O’Connor masters the juxtaposition of these neurosis with great control and radiance.

There is more than the carnal, the base, the sensational to our stories. But the great learning lesson inside Gwen & Ida: The Object is of No Importance is that we don’t have to have flashy Hollywood lenses through which to tell our stories; we simply have to tell them.

Running Time: Approximately 90 minutes with no intermission

Gwen & Ida: The Object is of No Importance plays through June 29, 2019 as a co-production presented by Nu Sass Productions & Uncle Funsy Productions at Caos on F— 923 F Street NW in the heart of the Penn Quarter district of Washington, DC. Tickets are available at the door or in advance online.