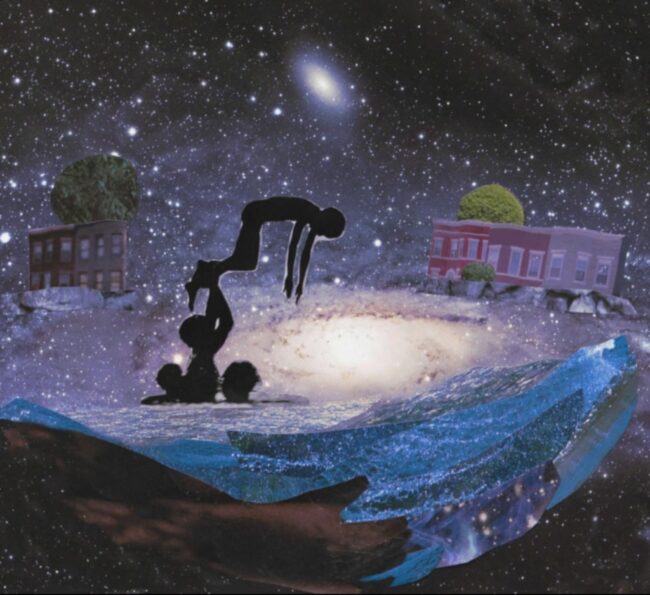

Dreams are dreams. Awake is awake. Know the difference. But if you don’t know— or don’t want to know? In stunningly beautiful narrative that blend magical realism with the burning yen to simultaneously connect one’s past to one’s future, Dontrell, Who Kissed The Sea is playing a limited engagement with Sisters Freehold currently at The Peale Museum for the next two weekends. This evocative coming-of-age journey, written by Nathan Alan Davis and directed by Makeima Elise Freeland, embarks on a journey beyond the imagination— into the wavy, watery lines of destiny, history, and self-identity. A remarkably captivating tale, this production is performed with pure “Skalent” (that would be skill+talent, as neither one likes to work alone) and has audiences pitching on the edges of their seats from start to finish.

If there’s a singular flaw in this production its that in their overzealous approach to heightened emotional explosions that occur in the performance, the company of Dontrell, Who Kissed The Sea, forget the unique space in which they’re playing— in so much that the high-vaulted ceilings, staging the performance in the round, in a historic museum room with no sound-dampening, results in some echoing/bad acoustics. This is really only a problem whenever someone is excited or shouting, which happens a lot during the performance (particularly during those more argumentative moments) and the speeches and text exchanges get somewhat distorted. That issue aside— this is a powerful and gripping piece of theatre that is telling a truly fascinating story; it’s a must-see for this February-March season.

Nathan Alan Davis’ script is sublime; there is a hyper-realistic blend of magical realism seamlessly woven into the every-day life of the story’s protagonist, which echoes in ripples and waves out into the ‘chorus’ nature of the performance. It’s almost like watching an epic odyssey-style play unfold— all of the characters, Dontrell excepted, double up as this pulsating heartbeat (in more ways than one) for the story and its journey. Director Makeima Elise Freeland has chosen to stage the work in the round— a resourceful and unique use of the Latrobe Room on the second floor of The Peale Museum. From the moment you enter the room, it is evident that you are about to embark on something extraordinary. Lighting Designer Charles Atwell sets the tone right from jump-street with the swirling gobos of blue on the ceiling and those of a more aquatic nature gently drifting about on the floor. Atwell also creates emotionally informed atmospheric lighting throughout the performance in a way that speaks to the narrative expression of the story but without becoming a whole focal point on its own. One of the subtler lighting effects that Atwell achieves— but it looks so realistic that it requires praising— is the ‘TV’ creation. Gentle flickering lights over the two ‘characters’ who are meant to be an on-screen soap-drama (and then later just over the father’s chair to imply that he’s off in a room with the TV on.) It’s so simple and yet so realistic, which creates that brilliant juxtaposition to all of the other less-realistic, more magical and spiritual elements at work in the production.

Augmenting Atwell’s work is the aural bliss of Alex Perry’s soundscape. You get the serenely hypnotic sounds of the ocean, of water, and that music that they play to lull you into this sense of wonder when you visit the National Aquarium at Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. (And Perry has synced that up with the scene that takes place at the aquarium!) There’s also the use of the ensemble/chorus as sound effects. The deconstructed, unified sound of marching/moving/stomping as we as breath and heartbeat, all created by the ensemble is clever and immerses the audience more fully in the experience. And what’s truly wild is that they say the words ‘breath’ or ‘heartbeat’ instead of making the sound (they also at times make the sound; it gives it this visceral edge that practically defies description.)

Costuming really had me pondering and admittedly I was spending more time than I’d care to admit trying to find the little pieces of tribal fabric that were— or in certain cases— were not stitched into various places on the characters clothes. At first, I thought the bright blue and orange patterned fabric was only hidden in places like the side-seam of Danielle’s jeans or in the mom’s robe pocket because it was meant to only be on members of his family. But then it was on Robby’s costume too (still not 100% clear whether or not Robby was physical family or just ‘so-close-you’re-family’) but not on the father’s clothing. The father had tribal fabric, but it was faded and worn and of a completely different color scheme and pattern. So that had me marveling the whole show through. Liz Miller (costume designer) did an excellent job at making the costumes realistic for an every-day ‘modern slice-of-life’ style show and then adding those little hidden scraps of past into her work.

Bruce Kapplin creates a cake-round-stage. Maybe eight inches high— not quite a full foot— but enough to be a centralized plinth for most of the action. There are four corners that branch out from the center, each one filled with some sort of setup— the lounge recliner where the mother and father character feature most frequently when they’re not in scene, a life guard chair in one corner for when Erika is introduced at the pool. And there’s a ‘road’ corner for when Dontrell is in the car with Robby. It’s a fascinating yet simplistic setup which encourages the audience to actively engage their imaginations, suspend their disbelief and just go with the flow.

Whenever I see the word ‘choreographer’ listed in the program of a non-musical performance, I always have this hope that it means there will be an actual dance and not just highly coordinated movements and blocking routines. Fortunately for me, Taylor Reneé delivers on both fronts. I can’t really discuss the proper choreography as it occurs right at the end of the performance and would be something of a spoiler but it’s thrilling; the intensity and whole-bodied-energy that pumps and surges through that routine is just wild; it feels feral and ancient and is astonishing to watch. But there’s also a great deal of choreographed blocking (by way of Taylor Reneé and director Makeima Elise Freeland.) The ensemble are more than just their characters; they are wind and breath, wave and sea, and a great many other elements and things that are intangible; often they’re just watchers too. It’s difficult to describe but it gives vibes of a modernized Greek Drama with somewhat less of the wailing and heavy tragedy. Freeland’s pacing of the performance is divine; you never get the sense that it’s dragging on too long, the scenic transitions are sharp and crisp, and you feel this current pulling you through the narrative. It’s a must-see because I’m afraid if I keep describing it, I won’t do it adequate justice and you won’t understand how truly impressive and moving it is.

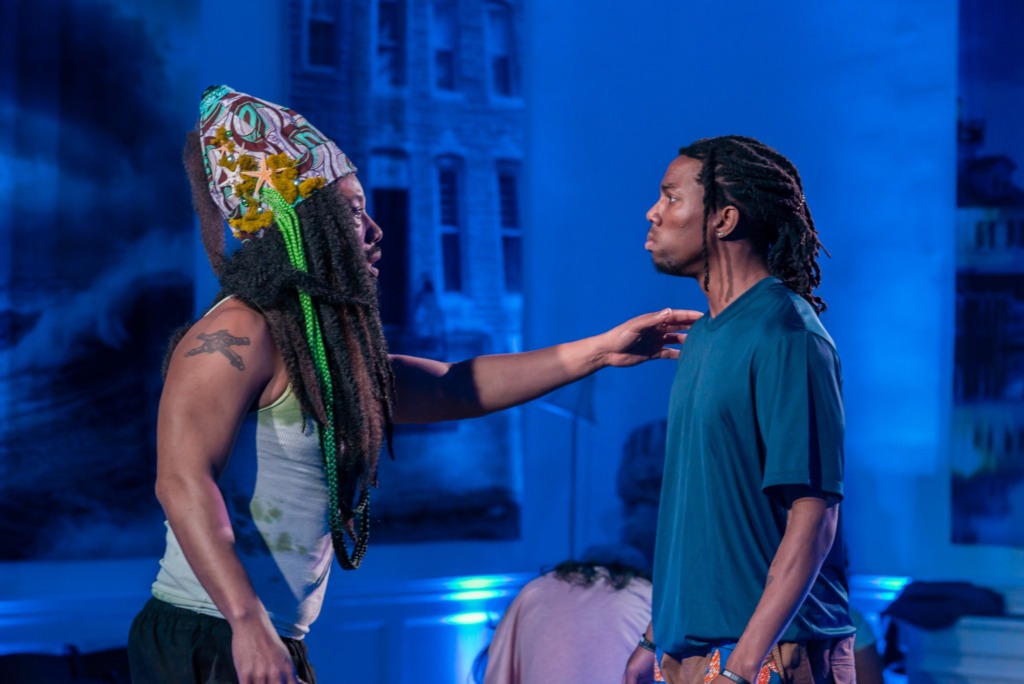

Everyone holds their own in this ensemble— Jae Jones, Sha-Nel Henderson, Autumn Koehnlein, Joi Kai, Maren Yolovia Wright-Kerr, Majenta Thomas— the move, breath, and observe as one. But also separately. Majenta Thomas, as the somewhat reserved and extremely nervous younger sister Danielle, portrays a timid character and yet you feel like you know volumes about her existence because of all that Thomas doesn’t say. The way she responds bodily— little fidgets, stiff posture, hurried responses when addressed directly— she wholly embodies this notion of easily startled, afraid of her own shadow, but still compassionate toward her brother.

As the street-savvy, chill-AF best-bud of Dontrell, Maren Yolovia Wright-Kerr absorbs the role of Robby with finesse, flare, and a completely mellow vibe. There is a deep-seeded camaraderie and kinship between Wright-Kerr’s Robby and the character of Dontrell, which helps setup some of the tensions between the Robby character and Danielle and Mother Sophia Jones later in the performance. Acting almost as an opposite, grounding resource, Joi Kai’s portrayal of cousin Shea is a figure on Dontrell’s life that provides reason and logic to all of the off-the-wall ideas. If Robby is the smooth and mellow ticket out the side window, then Shea is the reality under which Dontrell keeps forgetting to plant his feet. There’s something humorous and engaging about the way Shea approaches the character of Shay, who works at the aquarium, and yet something stoic and serious too; it’s a solid blend of a dynamic character.

The Mother, Sophia Jones (Sha-Nel Henderson) and The Father, Dontrell Jones Jr. (Jae Jones) are played a bit to the stereotype of a family that you might see on television and yet they’re so perfectly in their respective elements that you feel wholly encapsulated by their portion of the narrative. A good deal of the chuckles and humors come from the somewhat dysfunctional relationship between Henderson’s Sophia and Jones’ Dontrell Jr.— the shouting back and forth at one another from separate rooms, the insistence that the other is right or one is gonna show the other what’s what— it’s hilarious and true to family form; it puts the fun in dysfunction as it were. Henderson, as the ferocious and sassy mother figure, whose temper and whose love knows no bounds, finds an extraordinary way to balance this larger-than-life-in-charge personality with the love of her baby; that moment at the table towards the end of the performance “don’t ask me to get you a new scuba suit” is an emotional gut-punch that knocks the wind out of you and it’s delivered so simply you’re blindsided by it. Jones’ portrayal of the father may initially seem detached, but when he lets loose on Dontrell and goes on this emotionally charged tear of “I want bitches guarding my door” (a profound and beautiful reclamation speech for that term written by playwright Nathan Alan Davis) it’s enthralling. Watch out for Jones at the end of the performance as well, taking up a different mantle that will leave you stunned.

Have you ever been to the science center and seen one of those huge balls of electro-static light with the tendrils of electricity just slowly vibrating inside until someone touches the surface and then they start to zap and explode in a dervish of chaos? Autumn Koehnlein is as close to a human personification of one of those science balls that you’re ever going to get in her portrayal of Erika, the lifeguard-turned-love-interest. Also, shoutout to her brief portrayal as a very engaged ‘Nemo Fish’ and the body-language that goes along with moving this little hand-prop-puppet. Koehnlein has this effervescence about her— even in the vulnerable moments when she’s sharing deep, dark, and personal secrets with Dontrell; it’s infectious. And if the Dontrell character were melancholy or lost in darkness, it would be curative. But the Dontrell character lives in the clouds of murky history and dreams with magical realism and spooky futuristic messages serving as his navigational compass. So Koehnlein’s explosive frenetic bubbles are a combination for volcanic proportions when Erika meets Dontrell. The chemistry between the pair feels authentic; nubile and graceful at first, then almost soul-bound in the blink of an eye. They feed off each other’s energies and it makes the conclusion of this performance that much more jaw-dropping.

As the titular character, Jaylen Henderson is giving us the show of a lifetime. Engaged, juvenile and yet beyond his years simultaneously, there is something ethereal and wondrous strange about the way Henderson presents Dontrell Jones III. You get the sense that he is burgeoning on this discovery of self but it’s also deeper than that while at the same time feeling like he’s this uncertain boy who is trying to fake life until he figures out what it’s all about. It’s a riveting, mercurial performance that keeps the audience on the edge of the seat and wholly invested in his journey. He becomes an Odysseus of sorts— questing relentlessly. His physicality on stage draws you further into his spirals of reality; particularly when drowning at the pool, then rowing in the ocean. Henderson embraces each of Dontrell’s discoveries with a rawness and a newness; its as like each moment is his own personal epiphany and that’s a remarkable thing to behold on stage in one of these coming-of-age style tales. What’s truly impressive about Henderson’s approach to the work is that the character of Dontrell Jones III is often so caught up leaving messages for ‘future generations’ that the character is incapable of being present in the moment, but you never feel as if Henderson himself is not present in the moment. It’s a phenomenal thing to balance.

It’s really an invigorating theatrical experience; definitely worth attending; don’t miss Dontrell, Who Kissed The Sea, running at The Peale Museum through the first weekend in March as a production of Sisters Freehold.

Running Time: Approximately 95 minutes with no intermission

Dontrell, Who Kissed The Sea plays through March 3rd 2023 with Sisters Freehold, currently appearing at The Peale Museum- Latrobe Room— 224 Holliday Street in Baltimore, MD. Seating is limited and tickets must be procured in advance online.