Let them eat— s’mores? Following along through Season 35 at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, their world premier of Lisa D’Amour’s work Cherokee settles nicely into the “let them eat” theme of the season. In a TheatreBloom exclusive interview we’re talking with Woolly Company Member and Director John Vreeke about his involvement with the project and why it interested him.

Thank you, John, for taking time to phone in with us for this interview. Can you refresh the memories of our readers in regards to what you’ve done in the area recently or where they might know your name?

John Vreeke: Well I just did The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures over at Theater J. Let me see, before that was The Last Days of Judas Iscariot at Forum Theatre. I did Under the Lintels with Paul Morella at Metro Stage. He’ s actually in this show, he’s a good buddy of mine, great to work with. The last thing I directed for Woolly was Detroit, another Lisa D’Amour play.

How did you come to be involved with this new work of Lisa D’Amour’s and what was the appeal to want to direct it?

John: It really started out with Detroit. That play, and I think Lisa (playwright Lisa D’Amour) would say this also, but Detroit was a much easier play to write. That play came off of her pen much, much easier than Cherokee. We did the fourth major production of it. I think we did some really interesting things with it and we gave it a context that other productions didn’t get, but at any rate, Detroit had a great production history. There was no script manipulation, no script doctoring, or edits or rewrites when we did Detroit. Then Lisa came in at the end of tech and previews and was very happy with what we’d done. She liked what I’d done with the actors and the direction I’d taken them.

One night when Lisa and I were walking back to our respective housings I said to her, “What I really enjoy is working on plays from scratch.” I enjoy new plays in progress. I’d done that sort of work with Rajiv Joseph’s Gruesome Playground Injuries, and with Samuel Hunter’s A Bright New Boise. I’ve been at Woolly for about 12 years and have gotten to work on a lot of these great new projects through them. Anyway, we were just talking about that and Lisa said “I’ve got a brand new script called Cherokee.”

I believe at the same time Howard (Artistic Director Howard Shalwitz) had decided to read it. They were looking it over; it was a very rough draft at that point. So I figured ok, let’s be brave and daring. I decided I would say yes, even though I knew it was going to be a lot of work. They helped Lisa out with development funds and came back for a workshop in September and another two-day workshop in November. The Appetizer event was a part of that workshop.

That’s sort of the history there. When we came together five weeks ago Lisa continued to be with us in the rehearsal room much of the time. Every day she would come back in with rewrites and new pages. Just yesterday morning after our second preview we sat down and had about half a dozen edits. Not big edits, but tiny little things that helped clarify things.

You seem to sound like you actively enjoy having the playwright as a part of the rehearsal and development process. I’ve interviewed directors who sit on both sides of that fence, what is your feeling on the matter?

John: Well I think you have to set it up right. Right from the get go you establish a language and you establish a very transparent, open rehearsal room. In other words, what I find causes a lot of tension when a playwright is there is this: let’s say I’m directing a scene and there are actors in the room. Now, you may not know this as few people seem to, but actors— they actually have brains! And they actually know how to think. They become a very valuable part of the discussion process that happens with new works. I encourage actors to speak up and to say “Hey! Lisa, I can’t say this line.” Or say “Hey, I don’t know what this means, or maybe this needs a little rewrite.” Or whatever. And then the playwright might be able to explain how and why they wrote it and that might click for the actor. Or she can say “oh yeah I see why that’s a problem” and she rewrites it. I encourage actors to do that.

I don’t want anybody whispering in my ear in front of actors. So I say to them, talk directly to the playwright. I say to her, talk directly to the actors. We’re all adults here. If we have a disagreement we’ll talk about it. It’s not that scary. So once that’s established, having the playwright in the room is just another cog in the machine. A very important cog in the machine, but a cog just the same. Now every playwright is different. Lisa is a mature writer; she’s been around the block a few times. Now I’m not saying she’s old, she’s younger than I am, but she’s had plays produced and published many, many times before. So she was under no illusions about being a part of this process. Lisa is a very careful writer.

Sometimes you get a young writer in the room— and again not talking about age— maybe I should say new writer. You get a new writer in the room and they’re way too eager to please everybody. So when people start saying things like “Maybe you should change this line,” they jump up and say “Okay! What should I change it to?” And oh my God that’s a terrible idea! It can spell disaster very quickly. Lisa is not like that at all.

I’ve worked with the opposite type of playwright too. I’ve worked with guys like Robert Schenkkan who wrote Kentucky Cycle and he just won a Pulitzer for this LBJ two-part play he wrote. I’ve also worked with Richard Greenburg who wrote Take Me Out. Those guys have absolutely no interest in being in the rehearsal room. They will come and see a run-through, they will hand me their notes, they don’t care what actors say or think, and that’s that. Their notes will have specifics: these are the edits, these are the places where you’re not directing them right, these are the places where I think you’re going wrong, and these are the rewrites. That’s fine too. Every writer has a preference. I just gave you the whole spectrum of how all of that works.

I love having a playwright in the room. Yes, there is an extra level of work that I have to do as a Director, because I have to get a play up on its feet. But we’re also writing a play. With this process with Cherokee, at least the first week was all about the play. So unlike Detroit or a lot of the other plays I’ve done where I can start staging it immediately, I didn’t start staging this until a week after we started. That put us behind a little bit, and that made me really use every minute I had. Lisa’s play, by her own admission, is very, very adventurous. Cherokee is much more ambitious than Detroit.

What makes it so much more ambitious and adventurous?

John: Well it presupposes some stuff that the audience may or may not accept mainly with its themes. What it is trying to talk about is a much bigger and more primitive idea than it seems at first. It talks about “why don’t you and I get up at two o’clock today, walk over to our bosses and say: ‘I’m quitting.’ And go for a four-month walk.” That’s sort of a gross analogy, but that’s what this play is trying to address. It’s asking us to look at priorities that have been bred into our DNA. You know, what is successful? A satisfaction in your work? Or making money at your work? Or achieving notoriety for your work? Or achieving security through your work? These are all American capitalistic ideas of success. And Lisa is asking us to question that in a very, very interesting theatrical way.

I don’t want to give away too much about what happens, but one of the characters is really having a hard time with that concept. Four of them are just diving right in. But the one character that is struggling, I think most of our audiences are going to cross their arms over their chests and say “Yeah, I’m with him. These people are not real.” My job, well Lisa and my job, actually all of our job, the actors and the designers— the design by the way is very unique— is to create enough fantasy-believability for the audience to accept it. You know how you go and see Midsummer Night’s Dream and you know it’s a fantasy forest scene? And Puck is running around sprinkling fairy dust into the lover’s eyes so that they’re all transformed? Well that doesn’t happen, except for in a Shakespeare play.

Well there are certain instances in this play that are like that. You’re going to have to buy that premise in order to go along on this ride. There may be people who are going “nah, not buying it.” But that’s ok. There is a big-time factor of suspension of disbelief coming into play here.

This play falls into Season 35’s concept of Let Them Eat! And the tag for this show is “Let them eat s’mores.”

John: Yeah. That has nothing to do with the show but that’s ok. We’re not doing s’mores in the show. Let me give you a little heads up on the design here. This play, in it’s very, very early stages, was done at the Wilma Theatre in Philadelphia a year or maybe even 18 months ago in a very realistic campground set. It was lovely and a very legitimate way to go. I saw it and I said “I wonder if there’s something else we can do.” So we came up with a world that is much more museum-inspired. So if you go into the Native American Museum on the mall, you see carvings, you see etchings, you see totems, you see abstracted paintings and sculptures of the forest. That’s what we took as our inspiration for the design.

We are in a forest. But it’s very much a museum-exhibit type forest. We went with that approach to help inform the audience of the “suspend your disbelief” factor that’s coming at them. That kind of design tells the audience what they’re getting into. And then we bring the real characters on with all of their real REI camping crap. Tents, stoves, bags, fancy hiking shoes, expensive stuff you buy at REI.

So even if you’re not having s’mores in the show, how does the show tie into the “Let them eat” thru-line of the season?

John: You know, I don’t have a good answer for that. I never even thought about that. I think I would be making something up if I tried to give you an answer and I don’t want to do that. I don’t direct shows as a continuum from other shows or leading into other shows, I just direct the show. I think it’s clever, “Let them eat cake” obviously fit with Marie Antoinette. I think they went with “Let them eat s’mores” because it’s something everyone associates with camping. Although nobody who goes camping actually makes s’mores. I mean if you’ve got kids, maybe you do, but most serious campers do not carry around chocolate and graham crackers and marshmallows.

What is it that you want people to experience or that you want them to take away from the experience of seeing Cherokee at Woolly Mammoth?

John: I think there’s a kind of fantastical joy that we all sometimes imagine on our worst days at work where we say “Why am I doing this?” You and I are lucky because we actually work in something meaningful and something that we love. Let’s say we’re an oil executive or that we work at a bank or a big profitable business. We’re a cog in a machine and we’re there to ensure that these big companies continue to make a lot of money and we probably get paid pretty well to do so. But at the end of the day we sit down and say “what have I done?”

I like the idea that people can kind of escape that for a while by watching these characters on stage grapple with those ideas. They watch these characters go very deep into a forest— metaphorically and physically, we’re going camping!— and actually asking the question “can we actually change the narrative that most of us in our individualistic, capitalistic society have inherited and accept without question; can that be changed?”

Do you personally, John, think we can?

John: I think we can. I think a lot of people do. I think Lisa certainly does with her play. I think a lot of people can, whether or not they do something about it and actually follow through with it is another question.

Do you go camping? Do you enjoy camping?

John: Well funnily enough I live in Seattle. And my partner works at REI. No, I’m kidding. When we moved back to Seattle in 2009, which was a little sooner than I thought, my partner had lost his job and was looking for something to do. One of the reasons I love Seattle is because you can drive for an hour or two in any of the four directions and arrive in the most spectacular mountain scenery. Now those are northwest mountains, which are real mountains. The “mountains” that we talk about in the play are hills. Those things in Cherokee, North Carolina are not mountains. My partner loves hiking so I go along on the hikes often, when I’m not here in DC directing. And he loves camping, so in the summer we will go out and camp for a couple of weeks at a time. And we do not make s’mores.

You’re working with some Woolly Company members and repeat actors, and new faces. What is it like having performers from so many different walks of experience in this process of challenging American capitalistic ideas with Lisa D’Amour’s work?

John: Paul Morella is with us, and Jennifer Mendenhall is a company member, yes. Jennifer and I go way back, we’ve done many projects together and she’s a good buddy of mine. She is a meticulous actress and a demanding actress. If something isn’t right, she’s going to say so and we’re going to work it through until it’s right. I admire her for that. She brings an enormous amount to the party and I knew that was going to be very important when I was putting this cast together.

Paul actually came on board because Michael Russotto, who is another Woolly Company member, requested to drop out because he got another offer to do Sam Hunter’s The Whale over at Rep Stage. Right at that time Paul and I were working together over at Metro Stage and I liked working with him so I had him read it. Paul said “well, it needs some work.” And I said to him “Yeah, that’s why we’re doing it.” And then he said he’d love to do it and he came on board. So going into it I had two people that I felt very solid about.

Then Michael Anthony Williams was cast in the male African-American 50ish role, but he had to drop out because he got an offer to be in King Hedley II at Arena Stage, which was great for him as that’s much more in his wheelhouse. But it was a little late so we were scrambling a bit to find a replacement. A friend working over at Metro Stage suggested Tom Jones because he had the right age and feel to him, so we brought him on and that’s been very, very interesting. He is a very different kind of actor so he brings a lot of different skills to the party which has been really terrific. He brings a different viewpoint, and he’s a director! I’m not afraid of that, I’m going to use as many minds as I can when I direct something.

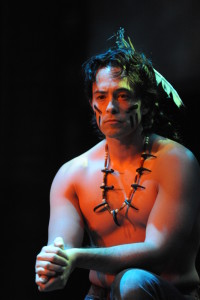

And then I have two youngsters. I have Erica (Erica Chamblee) who plays the African-American woman, who I cast initially, and she is just a delightful person. She brings an enormous amount to the table. Then I have a guy named Jason (Jason Grasl), who I want to say is 50% Native American, but I’m not quite sure about that. I don’t know which tribe…I know he’s not Cherokee, but he is Native American, and he’s a very handsome fellow. He brings an enormous amount of his own ancestral experience to the project, which is what Lisa was very interested in.

There are different challenges with each of these performers and their characters. So in the sense of five people performing as an ensemble, we’ve created that ensemble. I think they’re great together now. Before they all were from different worlds when we first came together, which was fine because it was sort of fun to begin an assimilation process with all of them.

There’s an interactive quiz on the Woolly site entitled “Are you ready to go Off the Grid?” Now, are you and your cast— if something were to happen— are you guys ready to go off the grid and survive without the gadgets and technology?

John: Uh, no. It’s a fun question, though. But no. We come to work in a nice warm theatre. We just pretend that we’re out there in the elements. We did not go all “methody” and decide to spend a night in some spooky campground in Shenandoah somewhere. No. We did not do that. We will not be doing that. We enjoy our comfortable rehearsal space. We enjoy our heated theatre.

Do you think there will ever be a point in your career where you get fed up with Directing, throw in the towel and do what some of the characters in this show are doing?

John: Well, oddly enough I think if you’d asked me that question 20 years ago when I was younger, I would have said yes. With every play I direct I have a couple of days where I just want to walk away. Making art is hard work. And sometimes you despair a bit. I’m 65 years old so I’m already thinking about how much longer I’m going to do this. I’m not making any hard and fast dates or plans for retirement, but I look at a guy like Michael Kahn (Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Artistic Director since 1986) and he’s what, 77 or 78? And he’s still active. Howard, who is younger than me, but he’s getting up there, we talk about at what point do you step aside?

I hope that when I’m in the rehearsal room babbling and drooling that somebody will tell me to stop coming to work. But to answer your question, yes, with every project that I do there are those few days where I want to walk out of the rehearsal room and keep walking. But that’s pretty normal. The next day I wake up and say “I’m glad I didn’t do that.” And I’m delighted to come back in and continue the struggle and continue the work. My partner always tells me when I have those moments of despair, “you do that every play, you’ll get over it.” It’s just a phase.

I’m actually at what many people think of as retirement age, but I’m not going to retire. I’m going to direct as long as I can because I like what I do. But I’m sure that as I get even older there will come a point quite naturally where I’m going to stop being invited back. Then I’ll stop.

Anything else you’d like to say about the piece?

John: I think it’s a very primitive, raw, original piece that I hope people will take a deep breath and go “hey, I think I’ll just go on this ride and watch these people, this looks like fun.” I hope that’s the case. If a lot of people come in clamped down or get caught up in the “that’s not real” part of it, I don’t think they’re going to have a good time. I think the audiences will lean into it. There’s a cool amount of cliff-hanger stuff and mystery of what’s going to happen going on in this play. So just on that alone it’s fun. You want to see how it all plays out.

Cherokee plays through March 8, 2015 at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company— 641 D Street NW in the Penn Quarter district of Washington DC. For tickets call the box office at (202) 393-3939 or purchase them online.

Click here to read the TheatreBloom Review of Cherokee.

Click here to read the TheatreBloom Review of Detroit.