The door never closes at Mama’s Place. Everyman Theatre is holding that door wide open as the 2015 New Year starts. Entering the back end of their 2014/2015 with Lynn Nottage’s Ruined, Everyman brings to the stage the harrowing and haunting tale of life in a small town in the Democratic Republic of the Congo where civil war is eminent, every man is danger, and the palm wine and the dancing are the only things that chase away the horrors of reality. Directed by Tazewell Thompson, this evocative drama is insightful and engaging, provoking the mind to action when it comes to the political state of existence as a woman outside of the comforts of our own culture and society.

Scenic Designer Brandon McNeel crafts a gorgeous interior for Mama Nadi’s place. But the trouble with his design herein lies with the exterior approach to symbolism. Outside of the bar’s local coloring is a wall panel of debris stacked up beyond the natural borders of the set. While this could be interpreted as the rubble of war crowded up around the watering hole to barricade the place in upon itself in an attempt to keep the house as a safe location, it reads as a contrived stretch of the imagination to show that the world is collapsing around them, with the detritus of the civil war piling up beyond their control. The barricade of ruined furnishings have other connotations as well and do not juxtapose well with the realistic interior of the bar. Despite these opposing factors, McNeel’s set interior captures the essence and spirit of the safe haven that is Mama Nadi’s with his earthen color schemes and sparse décor.

Lighting Designer Stephen Quandt takes the opportunity to untangle the more complex layering of McNeel’s set design with a much simpler approach to the lights. When the scene of relaxed enjoyment opens on Mama Nadi’s, a wash of gentle atmosphere and good-natured carousing is swept simply across the set with a dimming of the main lights and a subtle infusion of reds and yellows. Combining Quandt’s work with that of Sound Designer Fabian Obispo results in atmospheric infusion of moods and emotions. The tribal music that echoes through the scene shifts with the open-aired starry night skylights of the African Congo draw focus to the present reality of one of the show’s subtler messages; even in war-torn Africa where life has been ruined beauty can still shine through the darkness. This delicate placing of hinted symbolism far better serves Nottage’s writing than the overt and blatant approach of the scenic design. Their moment of startling thunder and lightning effects, which perfectly blasts apart a moment of emotional confession is one of many examples throughout the performance as to how they succeed at their craft.

The show’s main issue is the dialects that waver in and out of consistency among the actors throughout the performance. Dialect Coach Gary Logan has great success with company members Dawn Ursula and Bruce Randolph Nelson, playing Mama Nadi and Harari respectively, though even Nelson’s accent slips away when he becomes overly excited during a scene later in the production. Logan does not establish distinctive sounds for regional identification, particularly with the character of Christian, and the girls accents all run together but are mostly inconsistent, coming and going on certain words and phrases. This detracts from the action of the production and because the set and subject matter are so heavily focused upon, one cannot help but wonder if the accents were disregarded all together as a clue to the play’s location and time period, would the production have been stronger.

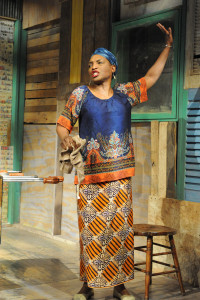

Despite Ursula’s consistent accent, her portrayal of Mama Nadi is somewhat static. While she does exude a sassy confidence that clearly asserts very early on that the bar and house are hers and no one should give her trouble because she’ll give it back tenfold, this attitude never rises much above that level. Ursula misses several potential opportunities to delve deep into the character in order to bring forth her struggle so that that drastic reveal during the show’s conclusion does not feel as if it comes shockingly out of nowhere but instead surfaces as a closely guarded secret that Playwright Lynn Nottage has woven delicately into the play’s inner workings. This creates an uneven portrayal on Ursula’s behalf because there are several moments throughout the performance where she is perfectly grounded and present, capturing the audience’s attention with her spastic gestures, raised volume, and vivid facial expressions.

To Ursula’s credit, the invasion scene is one of the most gripping deliveries of duress and fear with terror playing directly across her features in a palpable fashion that allows the audience to really experience her emotions. Despite her inability to shake off some of her lesser focused moments, Ursula does have a sturdy hand on Nottage’s textual conceptions, even if they aren’t always articulated and delivered as such. Ursula understands the character to a degree which takes command of the stage, but at the same time does so without solid follow through or intention. These inconsistencies make her portrayal difficult to thoroughly enjoy but also impossible not to like on many levels.

Taking full advantage of being the ‘lead girl’ of the house of sorts is Josephine (Jade Wheeler.) Despite having a snippy attitude that makes her character read as self-important, Wheeler’s portrayal of the girl does reflect a humbled respect to the Mama Nadi character even if it is done so begrudgingly. Lavishing a good deal of her attentions on the casually placed Harari (Bruce Randolph Nelson), Wheeler finds a way to unfurl situational tension with her body. She and Nelson have exceptional, albeit perfectly subtle, chemistry on stage for the few moments where they find themselves engaged. Like all the girls at Mama Nadi’s, Wheeler’s character has a tale of woe and plight, which she manifests in her outwardly catty and shrewish nature.

Christian (Jason B. McIntosh) who is an interloping character that attends to his own affairs whilst entangling himself with the house of Mama Nadi, is an unctuous fellow when it comes to getting what he thinks he wants and needs from the matron of the house. Versatile in his portrayal, McIntosh goes from a simple peddler of all varieties to having a politically informed opinion and his vented rage over the disgust of war is quite engaging. Watching him devolve into his own plight, particularly when it comes to the struggle with the alcohol and invading forces at Mama Nadi’s is gruesomely fascinating to watch.

Fortune (Bueka Uwemedimo) appears only briefly in the show and for fear of spoilers, his particularly identity and relation to the other characters shall not be revealed directly. Uwemedimo delivers one of the only mortifyingly redeeming moments for the men of this play wherein his confession reveals a truly tortured soul, conflicted with love and duty. This haunting tale follows not too long after Salima (Monique Ingram) reveals her own tragic story. Delivered with vivid recounting in gruesome detail, Ingram epitomizes emotional catharsis with jarring accuracy.

Two brutal forces of war, portrayed in Commander Osembenga (Manu Kumasi) and Kisembe (Gary-Kayi Fletcher) drive a great many of the tensions that occur throughout the performance. Fletcher, appearing as the lesser and more agreeable of two evils, is stern and firm but not without his charms. When juxtaposed against the rogue and prickish nature of Kumasi’s character, he practically looks saintly. Marching into Mama’s like he owns the place, Kumasi seizes command of not only the scene but the show, sparking fires of terror and fear in his wake. Possessed by an unshakeable righteousness, Kumasi delivers a character that is sickening to palate and nauseating to digest.

Little Sophie (Zurin Villanueva) is a pivotal turning point of the show. Capturing the essence of Nottage’s title, Villanueva plays her part with exceptional grace and fortitude despite the character’s delicate and shy nature. Her singing voice is a sublimely serene melody that wafts through her songs like a gentle breeze. Not only does her voice cut nicely through the music but it soothes the bigger picture of tension and strife in the way that only a natural-born singer can. Her vocalizations are warm and inviting and for just the briefest of moments you believe that she believes she can solve all of the problems therein with her singing. A truly captivating performance, Villanueva ensconces her portrayal of Sophie will of Nottage’s intentions from the text.

Running Time: 2 hours and 40 minutes with one intermission

Ruined plays through March 8, 2015 at Everyman Theatre— 315 W. Fayette Street in the West End Entertainment District of Baltimore, MD. For tickets call the box office at (410) 752-2208 or purchase them online.