There are no such thing as accidents. In tarot cards. Nor in theatre; particularly not when a fierce and evocative play finds its way to the Venus Theatre stage. Bursting into Feral 15: Feminist Fairytales, No Strings Attached, Artistic Director Deborah Randall sets the season’s bar exceptionally high with the world premier of Doc Andersen-Bloomfield’s God Don’ Like Ugly. A visceral and poignant tale that struggles to find rays of hope and light among the bleakness of a tragic and violent reality, this gripping emotional drama is an intense firecracker; the perfect play to kick-start the 15th season with a true bang. Gritty, emotionally abrasive, and unforgiving of its raw exposure to ugly truths, this new work pushes real life issues into your lap in.

Scenic Designer Elizabeth McFadden transforms the tennis-table theatre space into a moment in time that is long forgotten and yet eerily familiar. Between the wooden back porch and the derelict automobile it’s literally as if McFadden hopped in a time machine, traveled back to ‘sometime before the information age’ in East Texas, scooped up a quaint, albeit crumbling, backyard, and plopped it down in the middle of the theatre.

The car alone— which has a story all its own compliments of Randall and the Venus Theatre supporters— is disgustingly beautiful; a moment preserved in time that can never truly be experienced again except for in the recollective hazy deposits of the character’s memory banks. Symbolically representing so many elements of the play; the car is an active piece of the set’s reality while visually representing a metaphor of decomposition and wreckage. McFadden angles the car to look as if it’s an art installment; a piece of history crashed into reality like footsteps that have fallen out of time.

McFadden’s work with creating the porch is also striking. Illuminating her designer work is the Lightscape of Lighting Designer Amy Belschner-Rhodes. There is a seeping darkness in Belschner-Rhodes work that lingers in the periphery of the set; another representation of the dangers that lurk on the outside of the play’s immediate boundaries. Shining moments for Belschner-Rhodes occur during the remembered dream flashbacks; or the darkened fairytale moments. When the stranger bursts into the scene, backlight in a fascinating but ominous fashion, and his dance scene unfurls, the light is hazy and blue with hints of green, almost like a warped distorted memory. Belschner-Rhodes works the intimacy of the space to her advantage, creating haunting shadows— particularly with Bessie’s character— that subtly acknowledge the notion of ‘shadows being all that remain’ in some circumstances.

Rounding out the triple-threat design team is Sound Designer Neil McFadden. His work with music, both lyrical and instrumental, fits into the piece like a refined glove. The saucy French-Italian tango music that is featured during the fantasy-nightmare sequences strikes notes of passionate unease and delectable discomfort in the aural aspect of the show. McFadden’s lyrical song work has a slightly faded quality to it, mimicking a recorded tape or long-range radio broadcast sound.

Playwright Doc Andersen-Bloomfield tackles half a dozen intensely serious issues in the production including domestic violence and abuse, suicide, developmental disability in adults as well as all of the emotional burdens and strains that are coupled with these problems. Her exposure to the character of Esme, a developmentally disabled adult, is assertive, pushing the comfort zone of the audience to the edge of no return. Her writing is fluid and polished, and the morals and messages that are flawlessly woven into the play strike a resounding chord throughout the performance.

It is the simplistic, though exceptionally powerful, message of children’s natural need to please their parents that reads with a heartfelt solidarity (even if the motivating factor behind it happens to be birthday cake.) There tragic reality of domestic abuse is not skirted around, but boldly exposed and the mental anguish that accompanies this unfortunate situation is not shied away from but embraced. Andersen-Bloomfield has written an incredibly revealing and evocative piece of theatre that truly liberates the voice of women and children in a deeply mind-blowing manner.

Director Deborah Randall develops a brilliant balance in this production. Crafting a character that has a physical or mental disability is not an easy task, particularly when the disability of the character is as inherently present as that of Esme. Randall balances realistic truth with actress Cathryn Benson in creating the mentally disabled persona of Esme in a way that bares striking authenticity without being offensive or distasteful. True to the ensemblesque nature of nearly all shows produced at Venus Theatre, Randall creates a fluid moving thread between her characters; a bond that unifies even the characters that are strangers, making them all a part of an exceptional piece of new work.

Gray West, as the only man in the production, is identified only as The Stranger, and though is staged appearances are limited, his presence is strongly felt. The strikingly confident swagger that embraces his gait like a seductive hug radiates through his steps every time he sweeps in through the far house doors. Add behind him Belschner-Rhodes’ breathtaking lighting effects and McFadden’s unsettling soundscape and you have a terrifyingly enigmatic character that captures the attention of the audience through intrigue and fear, not unlike an exotic snake encountered by accident in the back yard. West’s movements, marked to perfection by Choreographer Maria Lin Yaffe, are unctuous yet sensual. This frightening combination, embodied with grace by West, is a harrowing representation of domestic violence; the way it disguises itself in fluid beauty but once revealed is truly vicious and destructive.

Though West is credited as ‘The Stranger’ it is Ann Fraistat’s character, SJ, who is really the stranger, or better labeled, the outsider to the intimate story of Esme and Bessie. Fraistat is an exceptional performer who gives the peripheral character of SJ an earnest depth while simultaneously keeping her hovering near the surface of her emotions. The progressive arch that Fraistat develops for the character is astounding, as her character enters the action of the play fairly late. But the expressive emotional disruption that she experiences is felt profoundly in little gestures and simple sayings. Holding the character of SJ together by a single filament of sanity, Fraistat embraces the unconventional situation in which she finds herself and delivers a delicate but determined glow of hope from deep within the recesses of her character’s darkened existence.

Much like the rust bucket of a car that permeates the set, Bessie (Nancy Blum) is trapped in a time that has long since passed and has developed a functional niche for herself in the delusions of that reality. Blum has a coarse nature to her portrayal of Bessie, which feels apropos to the nature of her relationship with Esme. There is a jaded bitterness about her that is delivered with a sharp tongue and deliberate certitude, which would almost be cringe worthy if Blum didn’t also imbue the character with the multitude of grief, struggle, and sorrow that she has experienced in her role. Several of her lines addressed at Esme are darkly comedic and hint at finding humor even in a bleak and dreary situation. There is ferocity to her presentation as well, not only vocally but physically in her shuffling gait and jerky movements.

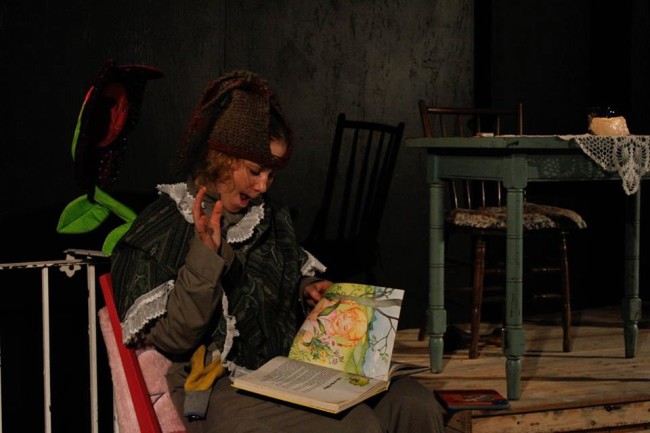

For Cathryn Benson there are simply not enough words to do her sensational performance justice. Calling it phenomenal hardly seems appropriate because it transcends adjectival descriptors. Benson fully articulates the existence of Esme as a developmentally disabled adult. Her physical and characteristical nuances are thoroughly established and layered into the performance; a remarkable portrayal of a character created from intense research and stunning performance ability.

Benson masterfully portrays the speech pattern of Esme in a way that replicates without impersonating or mocking the disability and fully fleshes out the character. She throws her body fully into moments of celebration and moments of tantrum. The facial expressions as well as her physical consistency and commitment to the character portrayal is nothing short of astonishing. Mere words will not do this performance miracle justice, not to mention the emotional depth and understanding Benson brings to the role. A true gift to Andersen-Bloomfield’s play; Benson draws the audience into Esme’s reality in a manner most profound.

Evocative, gripping work that pulls at the heartstrings, tears at the mind, and wends its way to shake up the soul, Venus Theatre is doing ground-breaking theatre that must be experienced this spring.

Running Time: Approximately 2 hours with one intermission

God Don’ Like Ugly plays through April 12, 2015 at Venus Theatre— 21 C. Street in historic Laurel, MD. For tickets call the box office at (202) 236-4078 or purchase them online