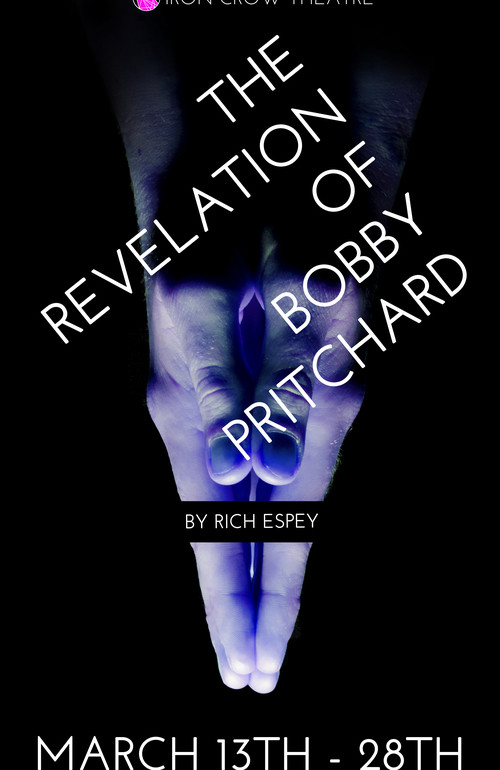

An inconvenient truth always beats a pretty lie in the long run. The central conceit— and cleverly coined phrase— of Baltimore playwright Rich Espey’s new work The Revelation of Bobby Pritchard. Making its world premier at Iron Crow Theatre, this engaging and compelling drama reveals a great many truths which are in need of being told. In a TheatreBloom exclusive, we sit down with the playwright to talk about the inspiration behind the story and just how it all came to fruition.

Thank you for taking the time to sit down with us today. Can you give us just a little bit of your local background to start with?

Rich Espey: I’m Rich Espey and I have had lots of plays done at the Baltimore Playwright’s Festival. Most recently was a play called Following Sarah, which was also done at Venus Theatre in Laurel. Hope’s Arbor was another BPF play and The Rainbow Plays was another one done at that festival. I did something with Iron Crow Theatre Company last year, during The Homo Poe Show. I wrote one of the pieces in that, it was called Trick. Those are the most recent things I’ve written that have been produced in and around Baltimore. I act a little bit, I used to act a lot more, but now not so much. The last thing I acted in was The Memo at Single Carrot Theatre. I don’t want to spend as much time acting these days as I do writing.

Writing is my passion. I’ve been doing it pretty seriously since about 2000. So roughly 15 years. I’ve worked hard at it. I’m a teacher for my day job so I spend a lot of my summers going to classes, and going to conferences, and taking courses when I can to consistently learn the craft. It’s not just about writing it, but studying it. I think that has been really important for my growth as a playwright. I think a lot of the structure stuff has to be practiced, it has to be learned. That’s what I try to learn and experiment with and be creative with.

Where did the inspiration for The Revelation of Bobby Pritchard come from?

Rich: So about six years ago I wrote a ten-minute play called The Choreography of Cyn and Marta, which actually appeared as the “yellow play” in The Rainbow Plays during the BPF in 2013. It previously appeared as a part of the very first thing that Iron Crow ever did, even before they were Iron Crow. I don’t even know if they had a name then, it was just a couple of people who had this idea of forming a queer theatre company. And there was this event called “Gay Expectations” at the University of Baltimore for pride around that time. They took four or five pieces and used them for that event, including The Choreography of Cyn and Marta.

Now, where that play started in my head? About eight years ago I had been in the Kennedy Center’s summer playwrighting intensive and a friend that I had met there, who was from California, she put out this call for something called “The Motel Plays.” It was a play festival that she was sponsoring and the criteria was that the play had to take place in a motel. There were a couple of other requirements, but mostly just the setting. I wrote this piece for that and it was about this old woman, Marta, who had come back to the home town where she had been born and she had her partner, Cyn, with her. Their goal was to get married on the courthouse steps of their small, conservative, southern town. Six or seven years ago that sounded like this incredible act of civil disobedience.

The thrust of that play was that Marta had figured out this was what she desperately wanted to do and Cyn was very afraid to do it. Cyn knew there were threats and that scared her but it was Marta saying “I have to do this because I have to do one honest thing to live before I die in this town.” That’s what the play was all about. It was a ten-minute play; it went back in time with a couple of flashbacks to explore their backstory. It has been produced a handful places, it’s a nice play.

A little bit later, I wrote a play called Hoya Saxa for a play contest at Active Cultures Theatre. They had this thing called Sportaculture, which were a series of short plays about local sports plays. So I wrote a play about this boy named Oren who is a football player and he comes out to this other boy who is a football player for the opposing team in their locker rooms. Hoya Saxa was also featured in The Rainbow Plays as the orange play at the BPF in 2013. That’s where Poss came from. I always liked Poss as a character and his whole arc of coming out and coming into his own comfortable name.

So I’ve got these two plays and I want to join them together somehow. I like them both and I want to mash them up and do something interesting with them. So then I’m at the International Center for Photography in New York, which I always like to go to when I’m in New York, because I always find it inspirational to look at all the interesting photography and it always gives me all these ideas for playwrighting. The particular exhibit they happened to have was about mid-twentieth century river baptisms. They had all these photographs of river baptisms, and all this great gospel and country music playing in the background. I looked at it and thought, “Oh my God, I wonder if anybody ever died from being baptized in a river?” It just stuck with me.

It was years of trying to figure out how to fit these stories together. And then of course stuff happens in the news and you read about these conversion facilities. I saw some stuff about this place in Tennessee where kids were spreading the message about what really goes on from the inside because they held onto their cell phones when they were really supposed to give them up, and the truth about what they’re really subjected to all started coming out.

All of these pieces just started coming together. I thought, “what if that was the town, and what if Marta goes back and what if the reason she has to go back is somebody died in a river baptism?” It all just came together as a story and it was really challenging. Trying to put all of those pieces together to come up with a coherent story; those were all the seeds that united to make this play. It did not come from any overarching idea at first. It came from all these different little things that needed to be knitted together.

There’s something I think everyone who has seen the show needs to know, and maybe you do answer it and maybe you don’t— fair warning this is a spoiler question so if you haven’t seen the show yet, don’t read the answer!— but is Bobby Pritchard’s demise as Marta says it was or is that just how she needed to remember it in order to cope?

Rich: You know, to me? I think the most important line in the play happens toward the end when Marta says to Hank “Just suppose Bobby did drown himself. Should he have had to?” And in the script it is literally written:

Hank: …{blank}…

Hank: …{blank}…

Hank: …{blank}…

There is a lot of air there. A lot of silent space. Because that’s where I really want the audience to see that Marta’s right. It doesn’t matter. We’ll never know. I don’t know whether Bobby drowned himself or if Marta is remembering the way she wants to or needs to remember it, but it just doesn’t matter.

What is it that you are hoping audiences will take away from seeing this show? What is it that they will be sparking conversations about when they walk away?

Rich: I guess I’m frustrated that it seems like there is no way forward with gender and sexuality coming up against traditional religion in some things. It seems like we’re in a place where it seems impossible to think about people not having to make choices. Marta talks all about it. She says “I had to make a choice, Bobby had to make a choice, Momma had to make a choice.” This is about impossible choices no longer having to be made. What I’d like people to think about is “can’t we get to a place where it can finally be ‘both, and’ where the cat is alive and the cat is dead.” Can’t we get to a place where we can have a community of faith and accept people for who they are? Does it have to be a forced choice for everybody? I hope not. I hope that we can move forward with that.

You use repetition a fair bit in your play, but not in a manner that makes it redundant. What is your process for working repetition into this piece and why does it work for you?

Rich: Well Suzan Lori Parks talks about rep and rev— repetition and revision. It can’t just be repeated it has to be something new. You have to make it familiar and yet unfamiliar at the same time. It seems natural to me that one of the key parts about Hank’s transformation in the play and his journey is that he has to remember some things about his childhood. I wanted him to have this memory that became more clear each time he had it. I’m a big believer in the rule of three. There is something very satisfying about the rule of three. So I knew Hank would have these three memory flashbacks to his childhood. One would be very vague, one would be a little more fleshed out, and the final one would be very rich and full.

With the idea of the six shots happening and always coming back to the moment in time of the next gunshot, I got some very good advice at a playwright development conference that I went to a couple of years ago with an early draft of this. In that draft I had something different happening each time the gunshot was fired and the person who was advising me said, “You know it would actually be really nice if you just had the same three lines spoken again so it would refocus the audience on where we are every time one of those gunshots is fired.” That’s in the play now. It’s just the same three lines that are spoken when the gunshot is fired and I think it does work very effectively. I think it does help to bring the audience back.

We see Marta have three encounters where she sees Bobby in her dreams. Again three is important. They’re all slightly different but somewhat similar. I don’t know, I just like the idea, especially in a play that takes a lot of work for the audience to piece together the story, I like having those anchors. It’s really important but you have to make them different enough each time so that they’re not boring.

You have not written the music, you have a composer that helped you with this project?

Rich: So I wrote the lyrics and I made up two of the hymns. I made up the one, “Go down by the river, go down seven times.” And then “Lead us down by that gentle river.” I made both of those up. The one that Margaret, the mother, is always singing, “The Water’s of Bethesda’s Pool,” that is an actual hymn text. I was never able to find the tune for it but the words are from a traditional hymn. I also wrote the lyrics to the country song that Marta and Bobby are working on writing.

I approached a student (Composer Abram Foster) at the school where I teach, Park School, and he’s actually taking some composing classes at Peabody. I asked him if he would be interested in setting the music. He said he felt really comfortable doing the hymns, he did not feel comfortable doing the country tune. So he did the hymns and I think he did a very nice job with them, and then Jonathan Jensen set the country tune. He and I worked on a project together a couple of years ago. He wrote the music and lyrics for my musical about William Donald Schaefer. Jonathan is a very good song writer too.

Do you have a religious background that you’re bringing into this work?

Rich: Not really. I mean I identify as a Quaker so that’s very different from the religion in the play. When I lived in Georgia I went to a Quaker meeting. It was very liberal, extremely off-the-charts, left-wing Quaker. It was the east side of Atlanta, which is a very diverse progressive community. But obviously very different from the rural part of Georgia, which I got to know very well. I coached cross country when I was teaching there, that’s where the play Following Sarah came from. We would go out on weekends, every weekend during cross-country season in the fall and with track in the spring. We were out in Greenville, South Carolina, or Birmingham, Alabama, or Rome, Georgia at some meet somewhere and when you spend enough time listening to enough people talk, and drive past enough churches you get the feel for it.

I coached a boy’s singing group when I was there as well. I helped chaperone the field trips that this group was a part of and we’d go to Charleston and other places and it always involved singing in some church somewhere. I actually attended a lot of different churches when I lived in Georgia, I was sort of looking for a home. Because I had gone to the Quaker meeting very early on in my time living there, found it to be a little too political and not enough spiritual for my liking. So I bounced around at a lot of different churches but nothing stuck. I went back to the Quaker meeting, which by then I really started to enjoy, but I’ve never been to a church like the Boiling Springs Church.

Is the Boiling Springs Church completely fictitious?

Rich: It’s fictitious in the sense that I made it up for the show. I’m sure there are churches all across the south just like it. But again, that river baptism exhibit, which led to watching a lot of YouTube videos about river baptism; it’s obviously a very important thing in that church. I made up the idea of re-baptizing people when they’ve fallen…although I think that does happen in some sects of Christianity somewhere. I didn’t want to make the church a scary church. I just wanted it to be a real church. The people of the church aren’t scary mean, they’re just, and well they are who they are.

They’re not even closed minded. Hank isn’t closed minded, he progresses and learns to accept. It’s ironic, the most open-minded person is Margaret. But she lacks any sort of vocabulary for talking about what’s going on with her daughter and with Bobby. She gets the whole thing, which is why she gives the money away. She knows that Marta has to get the heck out of there. But there’s no vocabulary, there’s no words, there’s no way to talk about it, it cannot be spoken, it just has to be done.

You have written it so that Margaret, who is Marta and Hank’s mother, is double-cast by the same actress who plays Kathy, Mary Charles’ mother, correct?

Rich: Yes. To me that was very important to have Margaret and Kathy played by the same person and for those characters to go against type. You would think that as time progresses people would become more open minded but you actually have a very open-minded old Margaret and a much more closed-minded person from the modern generation in Kathy. I was very careful to make sure that they both sang the same hymn and that they both interacted with the dress but the dress meant different things to them. They both interacted with Chess Pie, but again it meant different things to them. Margaret gives away the money and Kathy gets back the money so it became very important that it be filled by one actor, creating this really strong link between the two stories.

What is getting to finally put this play together, from all its pieces and seeds over the last almost decade, and see it up on its feet fully produced mean to you as a writer?

Rich: I was saying to somebody that I think this is the first time that I’ve ever felt like a play of mine was really ready to get on stage. It’s been many years of work to get it there. The reading of the first draft of The Revelation of Bobby Pritchard was done in January of 2013. It’s been a little over two years since draft number one. When I declare a new draft it gets a number; I’m now on draft 18, which is the most I’ve ever worked on a piece. Because I’ve spent so much time on it I feel like this one is ready. I’m really glad about that.

It means an incredible amount to me that Iron Crow has done the show because their care and concern and production values are incredibly high. I did submit it to another theatre company locally, and they got back to me and said that they would love to do the play but they didn’t think they could do it the correct way. And I really appreciated that. Honestly, knowing that theatre, as much as I love them I agreed. I don’t think they would have had what it takes, and that is not a criticism of them, it’s just an acknowledgement, and I love that they were honest about what they thought they could and couldn’t do for my work.

I think that was Steve (Director Steven J. Satta) has done so beautifully with it is that he’s just taken it and he’s made it feel really smooth when it could be a mess. He and I had the same exact vision of that. If the scene shifts and somebody hasn’t put on their other costume piece? Who cares, just let them put on their costume as their talking, it doesn’t matter. It should just all flow. They all know they’re in a play. We talked a lot about that. Everybody knows they are in a play. It’s all about this split second of life flashing before your eyes with those crucial events replaying in that split second and figuring out how we got here.

Are you a playwright that wants to or is able to be a part of the rehearsal process?

Rich: I like to be a part of a little bit of it. This was a really great process with Iron Crow. I went to maybe three or four rehearsals and was there to answer questions that people had. I was also really pleased with how everybody was doing with the process. I like to let things go and let talented people do what they want to do. People sometimes ask me “Is this the way you envisioned it?” And I have to say “I didn’t really envision it.” I just like people to take the work and do something interesting with it. I want them to do something creative and caring with it. It could happen a million different ways. I know Steve is a great director, I knew he was going to have a great cast, and I couldn’t be happier with the way it’s turned out. I didn’t know any of the cast before they came together for this, and I love the way it’s turned out.

If you have a revelation that working with this show has brought to you as a writer, or just as an individual working in the craft, what would it be?

Rich: I think again it’s the time needed to make something get to the place where it’s really ready to be put up on stage. What was really helpful to me was to pitch this out at various conferences and festivals to get readings of it. There was a reading in DC, there was a reading in London, which unfortunately I did not get to be a part of. They were having a queer theatre festival in London and I submitted thinking “well they aren’t going to get one about the American south over there.” But they really liked it because it was something they didn’t understand and that they weren’t familiar with. They were fascinated by it because they didn’t understand the culture. That was the feedback I got. I ended up skyping a lot with the director, and that really helped me to develop it. There were four or five opportunities to really listen to it and to get really good feedback. Each one of those helped to push it to a different place.

The last place that really made the difference was Inkwell in DC that happened about a year ago. There was reading of an excerpt there. That’s one of their processes and it brought about some really good chances to get some rewriting done with a wonderful Dramaturg that they provided. I think it’s development, development, development. That’s the revelation. I put that in my production bio on the website. I was just going to thank all the people who had either read, directed, Dramaturged, or had something to do with this piece. It’s a list of about 50 names. I think that to me is a revelation of this. You really have to have that many people to make it work. At least for me. I was very happy to have all those people involved in this process.

I think I like having so many people involved because I’m an actor too. Actors want to be artists, of course. I know that I’ve been in plays where I didn’t feel that the play worked. So when we did readings I really listened to what they actors had to say about what felt right and what didn’t feel right, what felt earned, and what didn’t feel earned.

During all these revisions what has changed the most?

It’s a character. The character who changed the most in that two-year time was Kathy. We had to figure out a way to make her seem real. I think it comes back to the feedback I got from the Spooky Action Theatre reading. And— SPOILER ALERT— for Kathy what had to happen had to be an incredible violation of something sacred for her. That’s when I made her the person who took care of the church. She cleans the sanctuary and tends to the chores of the church. That wasn’t in any of the earlier drafts. Why is it so important for Kathy? Because this is the most sacred space on earth for her. Why does she clean the church? Because she’s compelled to do so. So it is something therapeutic for her. But when it gets soiled beyond her repair, then there is no hope for her.

I didn’t want her to be dumb. She’d not dumb, she’s incredibly bright. I think having lived in the south, there is a stereotype about how people with a certain mindset must be stupid. That’s the northerner’s mindset. I never found that to be true at all. People’s mindsets were the way they were set but they weren’t dumb at all. Unfortunately, I think that’s where liberals fail. They try to reduce everything to being about intelligence, and I think that’s just so arrogant and unfortunate.

I think that’s also why Cyn is not a likeable character at times. So during that scene where Kathy asks Cyn to please just talk to Mary Charles, and Cyn responds the way she does, it comes from that mindset. She’s very abrasive. She’s not nice. She’s caustic. Unfortunately that’s’ the way a lot of northern liberals come off in this battle and I don’t think it’s healthy. It’s not going to help us move forward.

Anything else you’d like to say about the show?

Rich: No, not really. I mean, I do have a lot of fun creating character names. I did have a lot of fun doing that for this show. Like Bobby Pritchard. I said to my partner one time, “If the title of a play is The Revelation of Bobby Pritchard, tell me what it’s about.” He said “It’s about religion in the south.” Bobby Pritchard just sounds like something out of the south. So when he said that, I thought “Great! Fantastic! Exactly what I was going for.”

I had a lot of fun with the name Martha morphing into Marta, losing the ‘H.’ She calls Hank little ‘H’ at the end, and you know she left the ‘H’ behind when she left him and left home. And then the whole Oren becoming Spice becoming Pos. The name evolution happens there, and even Mary Charles becoming Mary Chuck, which again sounds very southern. I just have fun with these names as they morph. I like it when people are named different things for when they felt different things at different points in their lives.

The Revelation of Bobby Pritchard plays through March 28, 2015 at Iron Crow Theatre at the Baltimore Theatre Project— 45 West Preston Street in Baltimore, MD. For tickets call (443) 637-2769 or purchase them online.

Click here to read the review of The Revelation of Bobby Pritchard.