I’ll give you a picture, you give me a script in two weeks. Better yet, I’ll give you a play, well, I won’t give you a play, see, that’s the job of The Yellow Sign Theatre Company. And they could be giving you a love story, they could be giving you animal mutants. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then their production of Mike Jancz’ new work The Business End is surely worth one evening of your attention? Directed by Jeffrey S. Gangwisch, this still-life capture of a messy 1960’s Hollywood affair— the struggle of the business end as it were— will mesmerize you, lulling you into a false sense of security much like the era itself did to every b-grade screenwriter who came through Tinseltown at the time.

It never ceases to amaze the way a small company with infinite heart can not only tame an intimate found theatre space but master their production in it to the fullest extent of its use. Yellow Sign does exactly that in their current production, again making exquisite use of the bifurcation of the stage. With no scenic designer credited, the layout of the store-front makes an impression the moment the audience enters the space. There’s a je ne sais quoi that is intrinsically 1960’s Hollywood; maybe it’s the old fashioned rotary phone and crummy office furnishings, or just the general feng shui of the spatial arrangement, but something transports the audience to the timeframe in looks alone before the action even starts.

Lighting Designer and Technical Advisor Eric Gasior creates one of the most fascinating and yet most simplistic effects in the performance. Charlie’s dinghy dump of an apartment is clearly off some main drag on the Boulevard as indicated by the perpetually blinking neon lights that reflect through the room’s only window. This monotonous repetition of neon hues starts to grate on the nerves, enhancing the stress and ultimate insanity that Charlie experiences. Gasior’s work is subtle throughout, though well worth noting as hints of dramatic lighting are used to set a mood or enhance one that’s already been set by character interaction.

Lori Travis serves as the Costume and Makeup Designer for the show and while there isn’t much to be said in the way of male couture for the show, Travis’ work is spot on for dear Vera. The high-waist skirt and flowing silk blouses really land their mark, particularly with the more form fitting skirts and dresses that appear in the dream sequences throughout. Travis’ approach to 60’s era makeup is like something peeled out of Ladies Home Journal and looks every bit the part on Vera.

There is something to be said for capturing the essence of an era that has passed us by, particularly when it comes to reconstructing the minutia of that era, as very few people recollect b-grade Hollywood screen disasters immediately when the 60’s are mentioned. Playwright Mike Jancz working closely with Director Jeffrey S. Gangwisch, encapsulates the particularities of Charlie’s humdrum life in the Hollywood lot. Furthermore, Jancz gives each character their own specific voice through his use of dialogue, a factor which Gangwisch supports through his dialect coaching. This is expressively clear in the character of Maury and Harvey, who although are similar are distinctively separate from one another.

Jancz has a handle on the rhythm and patter of a 1960’s exchange, particularly when it comes to the business end of such exchanges. The intricacies of his plot rise and fall the way a bad b-grade movie of the time would and one cannot help but be drawn into it without even realizing that you’re enjoying the less-than-stellar subject matter. Gangwisch enhances the script further with a keen understanding of character interaction and exactly how to hold dramatic tension in a scene just long enough for it to be felt and then dissipate into the ether.

The most impressive thing about the performance is not in fact the script or the direction but the seamless video infusion of bad dream sequences. Gangwisch, who serves as the creator of the videos, streams a series of distorted live-feed style moments onto a screen above Charlie’s bed. They all start pleasant, many of a sensual and sexual nature, all of which end in a nightmarish fashion, jarring the character from his fitful sleep. This trippy, and almost psychedelic moment becomes a major highlight as it happens again and again throughout the evening.

While Maura (Ann Tabor) and Sally (V Lee) are only featured briefly in the beginning of the performance, and once later toward the end, they both make their mark on the show in a manner most unforgettable. Lee is swept up in the golly-gosh nature of a 1960’s gooey-eyed secretarial doll. She arrives later on the scene as a rather frightening looking clown, playing opposite of Tabor’s doll-like imitation. The pair punctuates their moments with pizzazz and are easily worth mentioning despite the brevity of their characters’ existences.

As congenial as she is convivial, Vera (Ellen C. Jenkens) is indeed some doll. Again with limited active line play between either Harvey or Charlie, when she does speak it sounds like a recording of the times. It’s Jenkens coy flirtations, easily mistaken for routine kindness and vice versa, that are worth praising; a simple smile here, a gentle brush-by there, and she’s fit for work in the office. Watch her figure slip in and out of the recorded dream-nightmare sequences on the projections, it becomes an enchantment all its own.

As previously mentioned Harvey (Patrick Storck) and Maury (Jon Freedlander) are similar in their construction but vastly different in their execution. Freedlander plays the milder of the two kvetchy and driven characters. With a gravely tone to his slightly accented voice he gives off more of the air of assistance and friendship than that of Harvey’s character. A true ball-buster with an ego and an attitude a mile wide, Storck lives the larger than life Hollywood producer with gusto and zest; enough so to poison any man’s pizza, but it makes for an intense showdown between his character and Charlie’s when words finally start getting exchanged.

The scene stealer of the show is Deucy (Jon Swift.) Spaced out on a permanent trip this psychedelic day-tripper is just what the doctor, or producer, ordered when it comes to needing muses and inspiration. With a far-out way of spacing out his pacing— both physical and verbal— Swift lives on his own little planet that just so happens to orbit the one that has crashed like a super-collider onto the stage of The Yellow Sign. A total scream as the audience delights in his hippy ways, Swift owns his cameo scenes and really lays the gravity of the situation down for Charlie when it comes time to find a way out.

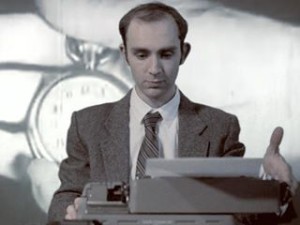

Charlie (Nicholas Parlato) is the central focus of the show but represents so much more than just a protagonist. Parlato’s invaluable perception in regards to the character’s internal monologue and thought process reflects in his posture, his actions, and more subtly in his spoken words. As is the way of most humans, when he expresses thoughts aloud to himself there is a drastic shift in the tone he uses, particularly once situations begin to spiral out of his control. The character arc and overall transformation that Parlato exhibits in Charlie is impressive given how little there is to go on; as is the style of the era so perfectly captured within the script.

While the subject matter is not for everyone, it is different and unique, especially by comparison to any other theatre in the era. Bringing forth a true appreciation for the low-brow arts, The Business End is well worth a peak if you can spare the time.

Running Time: Approximately 85 minutes with no intermission

The Business End plays through May 31, 2015 at the Yellow Sign Theatre— 1726 N. Charles Street in Baltimore, MD. Tickets are available at the door and for a discount in advance online. Advance purchases are strongly suggested as seating is limited.