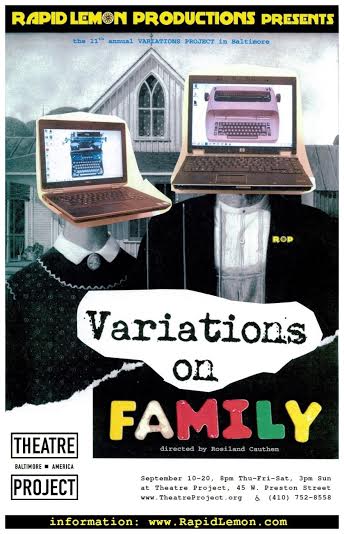

It’s Baltimore’s original 10-minute play festival. Now in its 11th run of production, The Variations Project is taking up residency in 2015 at the Baltimore Theatre Project. Now presented by Rapid Lemon Productions, a theatre company which evolved into the Baltimore Theatre Scene in 2012, the production is going strong and features eight works from local playwrights. This year’s theme: Family. Much like every year that preceded it, the subject matter that ties the shows together is broad and beautifully subjective. In a TheatreBloom exclusive interview, we’ve sat down with Rapid Lemon Productions managing director and founder, Max Garner, to ask him some questions about the production, his company, and how the Variations Project is contributing to live theatre in the Baltimore Arts Scene.

If you could start us off with a little introduction that would be great!

Max Garner: Well, I’m Max Garner and I actually grew up in DC doing radio in the 80’s. I worked in radio because I have a face for radio. In doing that and having a real fascination with music, and manipulating it and doing different things with music production, it got me back into theatre. I had acted back in high school, but didn’t we all. But right about the time I had moved to Baltimore I was dating a girl who had just graduated with a theatre degree, which you would think would be exciting because that meant she was working with all these companies in Baltimore. Except, she was a stage manager. So I never got to see her unless I was going to involve myself with the production she was working on. I was a potential theatre widower who was unwilling to become a theatre widower, so I just jumped into the booth with her. I board-op’d.

That particular theatre company happened to be AXIS Theatre (sadly, defunct.) And the Artistic Director of that company at the time said to me, “you know, with everything that you know about audio production and what you understand about music, have you ever thought about sound design?” And I said, “What the hell is sound design?” No one knew what sound design was in 1992. It was in its infancy. We kind of invented what our idea of sound design was as we went. For the ten years that the company existed, I ended up designing over half of the sound for their productions.

How did Rapid Lemon Productions grow out of your sound design work with Axis?

Max: So I intended to write a set of one act plays that were biographical and sort of related to one another. I was writing them about two famous musicians who died around the same time as each other but belonged to very different generations. And these two musicians were people that I felt personally connected to because of my radio work. Thelonious Monk, who died in 1982, and I on my college radio station at the time had to announce his death to the entire mid-Ohio Valley. It came over the AP wire as I was on the air playing a Miles Davis record. I still have the AP copy from 33 years ago. The other musician was Marvin Gaye, who was a whole generation younger of course, and died as a young man shot by his father two years later. He was killed on the day that the paying gig I had working at a tiny little AM station in Rockville changed its operating format to TOP40 music.

They were both interesting characters to me, what little I knew about them. I studied them. I researched them and just became more and more fascinated with their personal stories, with their struggles of mental illness, and their family situations. There were just some way too strange to be fictional things that happened to these men. I thought that it would be very interesting and potentially theatrical that would package together these two one-act plays about each of them. A wanted to call it Palindrome: Monk and Marvin. I liked the alliteration behind that.

I wrote a beginning of a piece about Monk, and figured out really quickly that it was too much for a one-act play. So was Marvin, for that matter, which made me write Monk as a full piece. It wound up being about an hour and 10 minutes without intermission. It was a two-hander, just Monk and his psychiatrist taking place late in his life. The theatrical sort of gimmick that happens in the play is that he has a psychotic episode, a hallucinatory episode during the session with this shrink. It happens for him and the audience, everyone is in it with him except for the psychiatrist. We achieved it mostly with light effects and it was neat. Writing about it allowed me to get into a lot of stuff in my own family and our history with those same kinds of things.

I swear this is getting to the answer of ‘where did Rapid Lemon’ come from. I tried to structure Monk’s language in that play, the way he speaks to be similar to his music. That very precise geometrical arrangement that seems chaotic and seems random but is in fact the opposite. He talks about the importance of the notes that you don’t play so I tried to write for the character in a way that was rhythmic and lyrical in keeping with Monk’s philosophies of how he wrote music. I love word play too. So as Monk is losing his mind, he goes into these palindromic rants. He gets into the face of his psychiatrist and screams “Go hang a salami, I’m a lasagna hog!” That palindrome has always been one of my favorites. He does that for a little while and then he starts spouting anagrams of the word palindrome. “Mineral pod! Pain molder! Plead minor! Rapid lemon!” and all of these other anagrams.

Okay, that’s important so don’t forget that, but fast forward about a year later where I’m working on the Marvin Gaye piece. And this piece ended up being a much bigger project. It wound up being seven actors playing 14 different characters. It was too big. It was a nice effort but it let me know that as a writer I’m not there yet. Janice Gaye, Marvin’s second wife, got wind of the project. She threatened lawyers and things. I was married at the time and my wife said “I’m not losing my house over this hobby of yours.” So I had to set up a corporation I decided I had to start a company, I might as well give it a cool-sounding name because that will be a fun project.

But all the names I had come up with— A.) were stupid and B.) were already taken. I’d love to be able to function on a truly non-sequitur plane, but I really can’t. I’d like to just be out there but I’m too rooted to sense-making and logic for that to really work. Rapid Lemon Productions sounds really cool, like it could be a non-sequitur, but it actually isn’t. Just like Single Carrot Theatre, I got the name from somewhere. Now, I didn’t steal a semi-famous history quote for my company name and motto, I used an internet anagram generator. I’m on Go-Daddy searching for names and that’s when the lightbulb came on to go back into my own script and look at those weird phrases that were anagrams of the word ‘palindrome.’ And I thought “Aha! That fits my personality!”

So I was going through them, “Pain Molder Theatre.” No. “Mineral Pod Theatre.” No. “Mineral Pod Players.” That was almost a maybe. We’d just have to do Soylent Green and the one about the aliens who come in and take over in their pods, it was a movie. It was an old B-movie that was remade in the 70’s with Donald Sutherland. But I wanted to be able to do more than that, so that name went away. And I settled on Rapid Lemon.

So you have Rapid Lemon Productions, how did your company come to inherit the Variations Project since your company is only three years old and this is the 11th incarnation of the project?

Max: I’ve been in love with the Variations Project since the very beginning. Personally, individually, and without any false modesty here, I’m the only common thread that’s been there through all 11 productions of it since it started back in 2005. I’m the person that’s been through the whole thing. I’ve wanted to run it myself for years. It started with Run of the Mill Theater back in ’05, and it was sort of an off-the-wall think-tank thing that came up at a party they were having and the theme ended up being Variations on Desire. At that point it was just a thing with no intention or even potential to become an annual thing, but obviously all that changed. And the project has cycled through homes, between Run of the Mill Theater (sadly defunct) then Arena Players and now Rapid Lemon.

The variations project actually varies in regards to the number of plays that get featured each year. This year it’s eight. We’ve done as many as 13, which is too many. And we’ve done as few as six, which isn’t enough. The happy medium seems to be between eight and ten. We are the original ten-minute play festival, and I know it sounds a little possessive when we say that, but we did originate it as far as Baltimore goes, and I know there are a bunch of other companies that are doing them now, but we like people to know this inspiration got its start with us.

One of the great things about Variations when it was with Run of the Mill, was Jim Knipple. He had very close relationships with people like John Barry and The City Paper people, so they were able to really get some of that extra publicity and recognition of the event happening because of his relations with those people. I’m working to rebuild some of that now, I mean Spotlighters Theatre and Rapid Lemon are doing cross-promotional ad-swaps in our programs, and I know Fells Point Corner Theatre has our postcards in their lobby and we have theirs here in ours. We’re trying to get the word out that the festival is still happening and that it’s an ongoing annual thing that is now going to continue under the roof of Rapid Lemon.

Talk to us a little bit about this particular Variations project, the 11th incarnation, whose focus is family.

Max: I actually had misgivings about the theme because I was afraid that it wasn’t going to market well.

Actually, can we back pedal for a second? I realize not everyone knows how the themes for each year’s Variations project is chosen, and that’s a pretty neat process, so tell us about that and then tell us about this year in particular.

Max: Okay. So Jim Knipple, the Artistic Director at Run of the Mill, he gave us the idea— after he left the company to go to Grad School out in California— to take donations from the people to choose the theme. You know we pick a bunch of different topics, boil it down to three main ones, and then let the audience decide. They put money in a bucket, or a jar, or whatever, with the name of the theme they want to see written about and the theme that’s gathered the most money becomes next year’s theme. That’s how we got Family for this year. And for the Variations in 2016 we currently have three themes being vote-donated on: Blame, Memory, and Space. Now, I think Memory is currently in the lead as far as donations go, but I think it would be really cool if Space were the one that was chosen.

But back to this year. I was worried that family wasn’t going to market well because people would be expecting one of two things. They’d either be expecting a bunch of short plays about wholesome family related things, or if it were still being hosted with Arena Players— which was where this year had started— people would be expecting these shows to be kitchen table dramas. Arena Players is the longest continually operating Black Theatre in the country and they are very proud of that. I’m proud to have worked with them over the years. There comes with that an expectation among some of your audience that you’re going to do certain types of shows. So when Arena Players said they weren’t going to do Variations this year, Rapid Lemon picked up the production and moved it to Theatre Project. It still worried me that much like at Arena Players, the general audiences of Theatre Project would expect certain things for this show.

It was bittersweet to see Arena Players let go of Variations because it had a good run with their company. But I’ve been wanting to run this project for a while, and I said to their Artistic Director, Donald Owens, “are you sure you want to let this go? Because if you do I’m going to pick it up with Rapid Lemon and I’m not giving it back.” And we came to a very happy and mutual agreement to keep the project going with Rapid Lemon. He knew how invested I was with this project. With his blessings, I guess that’s how you say that, he said “okay, go for it!” And now we’re here. I put a team together and this is the beginning of a Repertory Theatre Company, that’s my goal.

Explain what you mean by that.

Max: Okay, so I want to be a producing company that has a core group of actors, performers, and designers that we work with, but I want to be independent of structure in the physical sense. I don’t want to be stuck in brick and mortar. I want to be like— and this is before your time— but the model I would most like to emulate is IIA— Impossible Industrial Action Theatre. They were the best independent company in town in the 90’s. It’s sort of a throwback to the days of the players. Think old school London where the players would travel around in their caravan as a troupe going from venue to venue, township to township. I want us to have a group of actors that we work with, our directors and our designers, to do our work wherever we can do it. Now IIA was a resident company here at Theatre Project back in the 90’s, and that is something I’m looking into for Rapid Lemon as well because this space is quite versatile.

What do you think it is that a ten-minute play festival does for the theatre community in Baltimore?

Max: Oh my gosh! It does wonders! When I started writing I started writing ten-minute plays. I actually started writing plays because of the Variations Project. I saw how excited people were, these new writers of all ages, just being able to participate in the process. Even their stuff that didn’t get chosen to be staged, just hearing it read aloud at the table read during selection really engaged them and gave them an opportunity to get their work out there. It’s such a great motivator. Hearing other people say your words out loud, it’s a wonderful and exciting experience. I wanted to play along. It took me three years to write something that was decent enough to make it into this project. I will never forget sitting way up in the back of Theatre Project in 2009 getting to see the piece I wrote, called Lucky Me which was a fitting title because I felt so lucky to have it chosen to be a part of the project.

What was Lucky Me about?

Max: It was a ten-minute play in nine scenes. I know, that’s not what it’s about but how I structured it. It’s hard to describe. It was sort of a Twilight Zone terminal-disease misdiagnosis suicide thing with this dream-girl on roller skates doing this dance to Sly and the Family Stone’s version of “Que Cera, Cera.” It was silly and it was funny and people laughed. I can remember sitting up there and the first time, about 30 people— over half of them were laughing. I loved that feeling. Hearing people laughing at something funny I had written. I want people to feel that. Maybe not the laughing specifically, but to feel the joy and excitement of people reacting and responding to your work.

That’s what is so great about Variations, getting back to what it does for the community. The star of the project are the playwrights. It’s a playwright driven event. What’s great about it theatrically is bringing all of these different perspectives and voices together into a cohesive thing. That’s a big challenge too. It’s very easy to say that you have this overarching theme and use it as a crutch by saying “everything has to somehow connect to this word.” But you also have to make a show overall out of your eight or however many plays you have.

How have you focused on getting that cohesion out of this year’s show with these eight plays?

Max: These eight plays are very, very different from each other. They’re all written in different styles. Now what the festival used to do is each play had a different director. That is the one major change I’ve made this year. Instead of each of the individual plays having a different director— resulting in six to 13 different directors depending on how many plays we featured that year— this year we went with one director for all eight. It creates a unifying linearity among these vastly different plays, which are going to be different because each playwright has their own style, without changing the plays or the style in which they’ve been written.

The main theme doesn’t even really matter once the plays exist. The theme is the lines in the coloring book. Wherever the crayon goes, it goes, we’re done with the line once we get the crayons going. What we used to do before I took this “one director” approach in an attempt to unify the plays was production elements. So even though we had different directors they would all be playing in the same sandbox in the sense of having only one lighting plot that would cover everything. And limited choices as far as a set. But they were all just physical limitations that wound up being a pain in everyone’s ass because director’s weren’t getting what they wanted out of it, playwrights weren’t getting what they wanted out of it, and the struggle to get the plays unified was becoming more of a struggle than a goal. So shifting gears to one director I think has really unified the through-line of the plays around the theme without taking away from the individuality of the playwrights.

Our Director, Roz Cauthen, has this really tough and really fun job of working with all of these different plays and making them all fit together. I tell you, this has worked out a lot easier for our designers this year too. Having only one director coming to you with eight shows, as opposed to eight different directors coming to you, when you have limited resources because all of these shows have to happen in one space over the course of one evening, it has made things a lot easier on the production end of things. It’s actually emphasized the production value of the show overall, and I fetishize and romanticize the design elements of a production a little bit because I think like a designer. I am a designer.

Are you looking to keep the one-director approach for next year’s festival?

Max: Yes. I think this was a good working idea. I’m open to evaluate everything about this year’s run to see what really worked and if we can do it again. Having one director is absolutely the way to go, I think. I want to have a really good post-mortem with the actors after we close to see how they felt about the process, because I want to make sure it was working for them as well as it feels like it’s working on the production end of things.

You mentioned that ‘memory’ was the front-runner, or at the least, currently in the lead for next year’s Variations Project theme. Is that the one you hope wins?

Max: No. I mean, it’s in the lead, but I actually think it would be very cool if ‘space’ were to be the theme. Just think about it, there are so many different ways people could interpret space. I know you were starting to say space as in location, or space like the great beyond, but there are just so many ways that can be perceived. And I’m not worried that it would be too broad. Personally, I think a subject that would be too broad would be ‘love.’ Can you imagine? Variations on Love…we’d get so many submissions we’d never be able to narrow them all down because love can go so many places. My favorite nominee through the years, which didn’t even make it onto one of the milk bottles for donations, it was just written on a slip of paper as a suggestion by someone and thrown into the hat of consideration was “your mom.” Variations on Your Mom. Can you imagine?

I was talking to someone, I can’t recall who it was now, about an idea that we could float around for a play if Variations on Space were to be the theme. It would be this love story between two homely people. One of them has braces and the other has this really big gap between their front teeth and that that space would have something to do with the relationship. It could make it or break it, or do whatever. It’s just thoughts. Take a word and pose it any way you want to. That’s what’s so brilliant about space. I mean variations on memory has its merits too and will generate all sorts of ideas and great plays because memory in its most basic form is just story-telling and isn’t that all plays are? Stories being told?

Anything else you’d like to say about the production or about Rapid Lemon?

Max: We’re on the rise. We’re looking to do something in the spring so that we don’t just have Variations on…#12 next fall. We want to be an active company that does things. I’m not going to write anything between now and spring that we can do, but we have some ideas, maybe reaching out to local playwrights to see if there is something we can produce. Our mission statement is sort of about producing new and original plays, so we aren’t going to go reaching for an O’Neill or a tried-n-true from anytime more recent. Not sure really sure yet what we’re going to do, but we do want to have something going up in the spring. Follow us on Facebook so that you can keep up with the company and with what’s happening with the upcoming Variations Project.

Oh, and come see the show. It’s an amazing opportunity to experience the work of local playwrights, several who are new playwrights for the first time, and to really see what’s going on creatively in Baltimore as far as playwrights go. We have a great production with great people involved and people should come see us!

Variations on Family plays through September 20, 2015 with Rapid Lemon Productions at the Baltimore Theatre Project— 45 W. Preston Street in Baltimore, MD. For tickets call the box office at (410) 752-8558 or purchase them online.

To keep an eye on Rapid Lemon Productions, follow them on Facebook and check out their website!

For more information on what’s coming up next at Theatre Project, visit their website.