Artists are the real philosophers of the world because they are the ones struggling to communicate the real human condition. In a powerful new evocative work commissioned for Ford’s Theatre, playwright Jessica Dickey explores the notion of protecting the space around the art in her new heart-heavy drama The Guard. Receiving its world premiere upon the stage under the Direction of Sharon Ott, this fascinating new work is not without its levity in its epic journey of exploration through emotions and the notions of art and what it means to exist as humans in a world dominated by untouchable art. Gripping, timeless, earnest in its baser approach to the human condition, The Guard is an extraordinary experience that speaks the language of color and composition.

The set itself is an artistic accomplishment not only in its existence but in its fluid and somewhat mesmerizing movement. Scenic Designer James Kronzer fabricates a pristinely sterile museum interior for the opening scene with high walls that hold only the paintings which rest upon them. The artistic genius in Kronzer’s work is not fully witnessed until the first— and subsequent— scenic changes, which involves watching moving art as the walls rotate away through themselves to reveal a secondary and tertiary set, each more vibrantly echoing the time period in which they are set. Kronzer’s design work for Rembrandt’s studio is particularly poignant as it is decorated using only the four colors that the painter worked with in his masterpieces.

Interior lighting design is not something often praiseworthy as it is generally simplistic, however the work of Lighting Designer Rui Rita is well worth mentioning in this production. Rita’s striking use of singled spotlight is twofold, sitting first on the portraits of the wall and later on the individual performers who in their own way are much like the paintings on display in the museum. These fascinating pointed circles of light draw the authenticity of the setting and of the show’s overall themes into sharp focus throughout the performance.

Costume Designer Laree Lentz creates sharp contrasts from scene to scene as well as among the characters within the scene. The security guards of the opening scene are stuffed into pristine suits that reconcile the stereotype of the job and attitude with their couture while the interloping copyist wears a much more Bohemian modeled set of threads, reflecting her freer spirit. Lentz is appropriate to the time period for the second scene as well, but again focuses on creating contrast with the loose and daffy robes fitted on Rembrandt versus the crisp tunic and cloak saved for his son Titus. Lentz captures earthen tones in the second and third scene costumes, a notion that highlights human skin under Rita’s clever lighting.

Playwright Jessica Dickey has constructed a vessel that initially seems esoteric given its setting and initial starting point, but her vast expanses of emotional fortitude and relatable circumstances keep the show from drifting away into a sea of painter’s vocabulary. Her writing is striking and loaded with poignant and pensive quotes that stirs the mind thought-provoking quandaries. There is a poetic fluidity to Dickey’s writing as well, and not just in moments when poems are being recited. Her handle and approach to dialogue is natural, each character having a specific voice while still being able to directly react and relate to others in similar situations. Her overall thematic approach to the piece is somewhat haunting and at the very least a fascinating enigma to be explored.

Director Sharon Ott takes the canvas of Dickey’s work and expounds upon it with her own creative licensing. Intrinsic moments of simplistic emotions like grief or confusion becomes exponential wells of life-altering experiences as Ott carves a course through the characters’ emotional constructs. The pacing of the show is sublime; not moving too quickly or too slowly despite everything that does and does not happen throughout.

Character work is delivered at its finest and perhaps most versatile from Tim Getman, who starts the play as the loose cannon Johnny and closes the show as the subdued and mild mannered Martin. Delivering an obnoxious bombacity that could easily disrupt even the sturdiest of paintings, Getman is eagerly enthusiastic in his delivery as Johnny. By contrast his brief lines as Martin are so subtle that it literally becomes the opposites of day and night, so much so that it can scarcely be believed that both characters are being portrayed by the same actor.

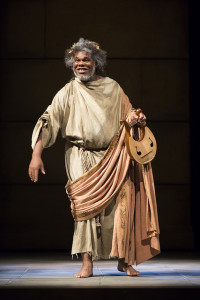

Though Craig Wallace’s time on the stage is brief, his dual roles are strikingly profound. Appearing first as Homer, Wallace lays his barked imagery upon our brains with an intense ferocity. Owning the root of art in his unending monologue as Homer, Wallace delivers levity, seriousness, and a great spectrum that falls between the two points during this section of the performance. Closing Homer with one of the most profound moments in the show, Wallace’s delivery is astonishing. Doubling up as the grumpy ailing Simon, his tongue-in-cheek biting snipes find the perfect amount of humor among the grave situation in which Simon is encountered.

Kathryn Tkel arrives on the scene as a copyist called Madeline and later appears as Rembrandt’s second wife, Henny. Tkel delivers a character consumed with inconsolable grief and does so with a raw and unapologetic force that drives emotions out from deep within her being. Juxtaposing this portrayal of Madeline against her softer and more femininely whimsical portrayal of Henny showcases Tkel’s versatility as a performer. There is a strangely unique bond between the way her characters interact with Rembrandt and Museum Guard Henry, respectively; though each have moments of a vulnerable bond that are rooted in Tkel’s ability to deliver unwavering moments of truth.

Josh Sticklin also plays to polar ends of the zany spectrum. Sticklin’s first incarnation as Dodger is edgy and laced with the modern hipster uncertainty that accompanies the stereotype. His speech cadence is slowed, his points are made with superfluous energy, all hallmarks of the modern generation’s apathetic distortion. As Titus, there is a hint of petulance in his youthful portrayal, though Sticklin manages to keep this more on the side of childish curiosity and determination. The regard with which he addresses Rembrandt is something to be astounded by, particularly in the way the bond between father and son is represented here. Dickey’s writing is at its most clever in this moment as Sticklin’s Titus delivers a flawless explanation of the strangely sized hands in one of Rembrandt’s most famous works.

Mitchell Hèbert commands the audience’s attention whether he is playing the relatively mousey Henry or the raving madman Rembrandt. There is a delicate sensitivity to Hèbert’s portrayal of Henry that endears the audience to his emotional plight and stirs up a great deal of empathy for the character. There is something tender and earnest in the way Hèbert experiences Henry’s world which allows him to transcend the glass of the fourth wall without breaking it so that the audience can experience his emotional turmoil first hand. As Rembrandt, Hèbert takes dutiful charge of the stage, mostly with his animated body and pitching voice, though the effect is not dissimilar in regards to the way the audience sees, feels, and experiences the character’s world. A remarkable work of art portrayed, Hèbert is creating a masterpiece live on stage before our very eyes.

Indeed an intriguing piece with a great many facets of art to explore, The Guard, dabbles into several worlds well worth exploring and is visually striking, emotional evocative, and performed with refreshing sensibilities.

Running Time: Approximately 95 minutes no intermission

The Guard plays through October 18, 2015 at Ford’s Theatre— 511 10th Street NW in Washington, DC. For tickets call the box office at (202) 347-4833 or purchase them online.