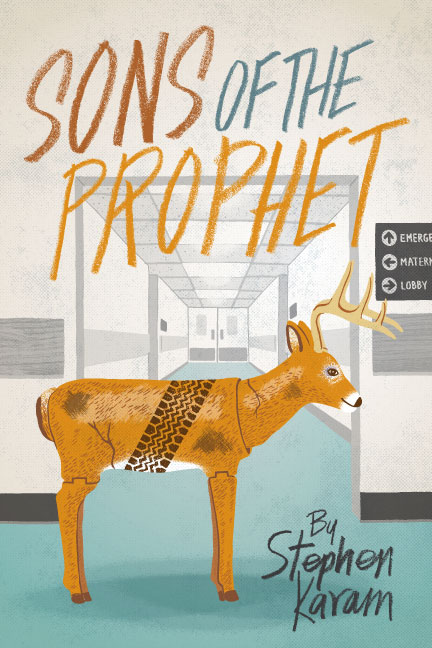

Nothing seems to be going Joseph Douaihy’s way. His body is racked with mysterious chronic pain, he desperately needs health insurance, his disgraced publisher boss is certifiably nutso, and his father has just died in the wake of a freak accident involving a plastic deer decoy, leaving him as the primary care-giver for both his younger brother and his ailing uncle. This sets off Theater J’s stellar production of Stephen Karam’s award-winning play Sons of the Prophet, a darkly comedic drama about a Lebanese-American family beset by one misfortune after another and their attempts to make sense of the constant hardship. Directed by Gregg Henry and superbly designed and acted by a talented ensemble, Sons of the Prophet is both a hilarious and touching rumination on suffering, loss, family, small-town America, chronic pain, healthcare, and football—just to name a few.

In the face of the Douaihys’ many troubles, it is probably appropriate that the spirit of Kahlil Gibran, the Lebanese poet and author of the perpetual best-seller The Prophet, permeates both Karam’s script and Henry’s production. The Douaihys are distant descendants from Gibran himself, and this tenuous familial connection fuels much of Sons of the Prophet’s plot and emotional conflict. While Gibran’s words brought comfort to the elder, freshly-immigrated Douaihys, his poetic turns of phrase and pat wisdom often create more existential strife for the younger Douaihys, and it’s Gibran that sets Joseph’s kooky sniffing after an exploitative new book deal. Gibran is present in the technical aspects of the show as well: projections of Gibran-esque titles (On Friendship, On Pain, etc.) divides the scenes, and Luciana Stecconi’s classical, cut-from-stone set evokes a spiritual, temple-like space that serves as a publishing office, a living room, a physical therapist’s office, and more.

Sons of the Prophet is a tough script – it is by turns clever, touching, and nervous, full of overlapping dialogue, stammers, and apologies – and in the wrong hands, I’m sure it would be incredibly difficult to watch. Gregg Henry’s cast at Theater J, however, was superb, and they all expertly navigated the juxtaposition between the hilarious and the tragic. The excellent Chris Dinolfo carried the weight of the narrative with ease, and imbued Joseph with a perfect blend of strength and uncertainty. Tony Strowd Hamilton brightened every scene he was in as Joseph’s younger, geography-obsessed brother Charles, and Michael Willis offered a wonderfully reserved portrayal of the boys’ cranky, ailing Uncle Bill. Sam Ludwig convincingly portrays Timothy, a white-collar, memoir-writing young reporter in search of bigger stories and who appeared to be reading (at least to my eyes in Row I) Dave Eggers’ seminal young-man-memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (a genius stroke by props designer Britney Mongold.)

Even the featured players were a joy to watch. Jaysen Wright took a role—Vin, the teenaged football star who set up the offending deer decoy in the road—and gave it such weight and specificity that I wish he had been in more scenes. Vanessa Bradchulis and Cam Magee rounded out the ensemble as a rotation of hilarious and well-meaning doctor’s assistants, ticket takers, and obliviously offensive school board members.

However, it is Brigid Cleary as Joseph’s painfully inappropriate boss Gloria that ran away with most of the show’s laughs. As a woman reeling from so much emotional trauma of her own that she must participate and wallow in everyone else’s, Gloria invades nearly every private moment in the show, trailing her own emotional baggage and inappropriate comments into the Douaihys living room and a private school board meeting. Cleary had the unenviable task of humanizing Gloria the opportunistic grief-monger, and did so with ease, giving us just a few glimpses of genuine heart amidst all the crazy.

Ultimately, I found it hard to accurately capture my experience at Sons of the Prophet in words. There is so much at play—the mishmash of cultures, languages, and classes, the conflict between generations, religion, immigration, and more—and it is so expertly woven together that it was difficult to parse out the particular strains until after the show was over. Even now, I am still processing much of my theatrical experience, and I can only tell you to go experience it for yourself. All in all, Theater J’s Sons of the Prophet is a moving and hilarious 105 minutes at the theatre, and well worth seeing before the holiday season is over.

Running Time: 105 minutes with no intermission

Sons of the Prophet plays through December 20, 2015 at Theater J in the Washington DCJCC’s Aaron & Cecile Goldman Theater— 1529 16th Street NW in Washington, DC. For tickets call the box office at (800) 494-8497 or purchase them online.