Circle, circle, dot, dot— now you’ve got your cootie shot! A fond recollection for a great many of the Gen-Y kids, but what does that mean in this modern world of sexual fluidity and polyamorous relationships? Playwright Ryan Nicotra, the Founder of BOOM Theatre Company sits down to explain his new work Circle Circle Dot Dot in a TheatreBloom exclusive interview. See what Ryan has to say on polyamorous relationships and why he’s chosen theatre as his platform to broaden the experience.

If you could give us a brief introduction of who you are and what people might recognize of your work, we’ll get started.

Ryan Nicotra: My name is Ryan Nicotra and I’m the Development Director for Single Carrot Theatre, the former Company Director for BOOM Theatre Company. I have written and directed and performed in over two dozen plays with BOOM based in Bel Air, Maryland.

And what is the current project you’re working on?

Ryan: I’m currently writing the next BOOM production, which is a new play called Circle Circle Dot Dot. It is, I think, a fabulous story of four young people who are in the final stages of a poly-relationship. It’s no secret that there’s sort of a clock ticking when the play begins. It’s something that I’ve been thinking about for a very long time and that I’ve been wanting to write. Now it’s finally come to be.

Is this your first experience with playwriting?

Ryan: I’ve adapted about a half dozen works. But that’s technically taking somebody else’s story and making it my own. This is my first completely original work. It’s not coming from someone else’s work, but I would say that the works that I’ve adapted have influenced it. One of the works that I adapted that really stuck with me was Chekhov’s The Seagull. Adapting The Seagull made me realize that you can have a large cast of character or even a small cast that all have very different story arcs and they can all coincide or it can be harmonious in a plot. There are a couple different sub-plots that are taking place in this work, but when all the characters are in the room it reads as one cohesive story. Even though you’ll recognize these characters and note that there are other things going on besides what’s taking place in the room, it’s really exciting to watch when they’re in the room how it influences what is happening in the moment.

The title of the play takes a great many of us, at least from Gen-Y, back to the childish cootie-related nursery rhyme. Can you tell us a little bit about the title and its significance or relation to that nursery rhyme?

Ryan: Absolutely. We used to do cootie shots in kindergarten to protect ourselves from either boys or girls or from anybody, sometimes from both! I’m just really curious as to where that impulse goes after childhood, to protect ourselves from love and from the people that we love or people that may represent love. I don’t buy that we grow out of those things. I don’t buy that we don’t come in with walls. This is a play about four people that all love one another and yet they’re all coming towards each other in a different way. I talk a lot about magnets when I talk about these characters. I don’t think that each magnet has the same power and not all of them are even in sync.

For instance, there are some basic ground rules that these four people have set for their relationship. They don’t color outside the lines, they don’t cheat, they are exclusive to the four. They don’t couple up, and that also includes in terms of sexuality— they’re not restricting from other people. It’s hard to police sex in a relationship. There’s this element that goes back to coupling up— these are loose rules, they aren’t hard and fast and there’s no metric for it— but in terms of sexuality the rule that they set is that they keep the bedroom door open.

You’ve mentioned that they play involves a polyamorous relationship between two men and two women. Can you explain to the readers what polyamorous means to you as a playwright or even just as an individual?

Ryan: Sure. Most relationships that we’re probably used to are between two people who are in a committed, exclusive relationship. A polyamorous relationship is not much different in the sense that it’s a committed loving and exclusive relationship it’s just between more than two people. A lot of the conversations that I’m having with the cast and with the director comes back to “don’t think about the sex of it” because that’s a part of it but that’s not why we’re looking at these characters. We’re looking at these people in terms of love and commitment and trust and boundaries. We’re looking at how they’re being changed by being in this relationship and how they are changing others by being in this relationship as well. It’s really meaty and exciting to work on with the actors.

Who is directing this piece?

Ryan: She’s a new director named Samantha Allen. Samantha has performed and worked with BOOM for three or four years now, but she and I have known each other since we were children. That’s kind of the really amazing thing about working with Samantha and with this cast, I’ve known most of them for so long that it almost feels like a family piece. This feels like a legacy work for this company. I say that because we’re not on-boarding anyone for this particular project. Everyone that’s involved with this project has done multiple projects with BOOM before.

Who is involved with the show?

Ryan: Victoria Scott, Joshua Fletcher, Anthony Chanov, and Jenny Hasselbusch. That’s the resident ensemble of BOOM and people who are just as involved as the resident ensemble. It’s really exciting when you have this core of people who have been working together for years because they have this inherent trust among them. I think a piece like this has the potential to make it so that they cannot be stagnant, or grow stale or complacent. I think that in a way it’s really exciting to churn the waters a little bit and see what they do with this sort of play. I think after doing this play they’re not going to be able to see each other in the same way as people, not just as performers in the show. I think they’re going to walk away with very different and hopefully better understandings of each other as people.

Do you believe that your work has a major dramatic question that it answers?

Ryan: I think that each character has an arc that asks a different question. It’s hard to answer because I think everyone who watches this show is going to inherently gravitate to one or maybe several characters and the question created by that character’s story arc may become the major dramatic question to that audience member. I’d like to think that as adults we have all either dated these characters or perhaps even have been these characters in relationships. I know I certainly have and I believe most of the people in this cast have. Maybe the big question is “What happens when people are defining this new form of love for one another and what happens when that form is broken?”

I think it’s really just questioning what these people want out of love. I think for some people it’s just a personal fulfillment, but I think for others they are a little bit more evolved and that they are looking for people that they can build a home and a family with. There’s also someone in the relationship who is with the group because they want to be with one in the group. This is their only chance to be with this other person. That’s actually a secret that is exposed very early on in the play and the group has to adjust to that and deal with that and how it changes their dynamic.

It would seem that a great many people sit on a clearly defined side of the fence when it comes to taking a stance on polyamorous relationships. How do you feel that’s going to read to your audience?

Ryan: I don’t think it would be appropriate or fair for me to speak for poly people or people who are in polyamorous relationships. I think that would be a false representation and inaccurate. I think there are people who can speak to it much better than I can, but with that said I’ve done a lot of good research. I’ve talked to a lot of people who are in polyamorous relationships.

You are not currently nor have you ever been in a polyamorous relationship?

Ryan: No. I have not. But I have really good friends who have informed me of the process. I’ve asked really good questions of these people. And the one thing that I’ve really always been curious about is jealousy. I asked, “Don’t you get jealous? I get jealous when I’m with one person.” And I want to know how that’s handled and balanced, and how do you not get jealous being with others. What was surprising was that in all my interviews of the people I talked to told me that jealousy is kind of what makes it really spicy and exciting. Poly almost feels like a different flavor of relationship. It can be very exciting. It can be very passionate. There are examples of relationships that are very long-term. They’re built to last, but I think that we don’t really have a model for it because we’re still trying to figure out what it means to be poly. Some people just can’t get over the sex of it.

What is it you are trying to do by writing a play about polyamory?

Ryan: I’m trying to challenge everybody to take a step back and explore it through the lens of relationship building and love. I also want people to acknowledge that sexual— I guess I’m going to call it sexual deviancy— that sexual deviancy or new forms of love are not as deviant as they seem and they’re not as new as we feel they are. They’re no less valid than other forms of love either. I think that is going to be interesting for a Harford County audience. One thing that I’ve found is that a relatively homogenous community like Harford County— they don’t want homogenous art.

The people who come out to see these shows and end up liking these more edgy or new and challenging works are not the people that I would have expected. For instance, when we did Prometheus Bound, it was Greek tragedy, I actually invited a woman who was homeless. She was sleeping in her truck, I happened to know her, so I sent her and her family some tickets to come and see the show, it was one of my earlier works. I didn’t know what I was going to get, I didn’t know if I was going to be insulting her by inviting her to this play which I thought was going to read as really heavy and difficult. But I also didn’t want to exclude her so I made the decision to invite her and let her decide for herself how she feels. For the three years that we remained in touch she raved about that show and that was the first time that she had seen a play.

I think that she really taught me a lesson. You really can never underestimate your audience ever. I ask a lot of my audience regularly and unapologetically so. But I also ask a lot of my artists and I also ask a lot of the field. I think it’s because if we’re looking at the bigger picture we can recognize that art can change lives. Theatre can change lives. Theatre can change society; it does change society. I’m a firm believer that when we’re exposed to people, cultures, and ideas that are not our own they are growing experiences and they make us better people for having had them. I’m perfectly content to live with asking a lot of people to go with me there. Sometimes it’s a home run and we really get it right. Sometimes we swing really hard and just barely get on base. Those are all great things. There’s a reason that we mix safer program with more edgy works and that’s because we have to build trust with our audience.

The year that BOOM produced Steel Magnolias, which to this day is the top grossing show in the company’s history in its entirety, we followed that show up with a Paula Vogel play, The Baltimore Waltz. And we actually had a really high turnover rate. A lot of people who had come to see Steel Magnolias heard about us doing The Baltimore Waltz, they knew the people in the show, and they took us seriously. Our audience knew that we weren’t going to charge them for a show we didn’t believe in and that really paid off. A lot of people came and saw that show. There were more familiar faces at Baltimore Waltz than I’d ever seen at a BOOM show. That’s the work we have to do to get audience to trust us.

With Circle Circle Dot Dot, I’m not pushing anything crazy, edgy, or experimental except for ideas. It’s a linear plot, it takes place in the course of one day. It takes place the day of the show. It’s easy to follow. It’s not something that you need a PhD to understand, you don’t even need a bachelor’s degree to understand it. I think a very cool parent could bring their kid to see it and they would get it.

What would you say has been your biggest challenge with writing a play on a subject matter where you do not have any direct experience?

Ryan: So I think two things, one I think first and foremost I’m a director before I’m a playwright. Being a director you have to know how to talk to people, find good information, and make sure that you’re not speaking for people when they can speak for themselves. It’s like checking your privilege a little bit. You have to be open to learning, open to getting it wrong, you have to be willing to explore it, knowing you’re not going to get it perfect, but trying to do so anyway. The other thing is that you have to accept is that after you do all the good work, approach it with integrity, and check your privilege that you are talking to good people who can offer you good information and insight to that lifestyle but you have to not make it harder for anyone who does live in that reality.

We had similar conversations when we were doing Macbeth, in approaching it from a very diverse gender spectrum. We changed the main gender identity of almost every single character in that show. It resonated really well with some people and it didn’t resonate well with others. I think that’s okay, there’s room to grow on it, and there are always ways to make your choices more articulate. I am really excited to be working with a company that really celebrates diversity and really wants to produce works that bring diversity to the fore without condescending or speaking for people when they themselves can speak for their own identities.

How do you justify giving a voice to a subject that isn’t necessarily yours to tell?

Ryan: I think we do it as a field all the time and I don’t think that it’s always necessarily bad. If you want to talk about artists producing outside of their cultures…Shakespeare’s British. He’s not our culture. If we were to stick within our cultures than none of us should be producing Shakespeare because who are we to be speaking for that era of British history? Now, there’s a greater conversation to be had about just how much time Shakespeare gets in classrooms and on stages, he’s brilliant but he’s not the only brilliant one out there.

I think I’m okay with this work at the end of the day because it does come from checking your privilege, talking to actual people who have experience and asking the right questions of those people. It’s also about recognizing that you are not the spokesperson for a community. You can ask questions about a community, you can engage a community, you can make art with and for a community, but I think that there is an ethical consideration where if you respect the people you are making art about that they will be included in the process throughout the entire process.

You said that you interviewed friends of yours to better understand polyamory and polyamorous relationships. Are any of your characters inspired from these real life people?

Ryan: Oh yes! Lots of dirt in this play! Like I said earlier, with every character in this play we’ve either all been them or we’ve all dated them. I’ll talk a little bit about each character. Now, I can’t name names, but if you know my people, you’ll know. But I’m not going to name names, I’m not here to praise or shame anyone. That’s the most true thing that I can say. But many of these characters are being written in the voices of the actors who play them. That’s one of the advantages of working with an ensemble company. Knowing these people and working with these people I have a privilege where I can develop something with them. They are writing their own voice. I’ve given them the scripts and I’m working with each actor to make sure that the dialogue feels very natural. I’ve actually told them all “You can press the bullshit button at any time.” If something doesn’t feel natural or it doesn’t feel right, hit the button and let me know and we will resolve it. I have no ego in this. I’ve worked with a lot of playwrights and I know what it’s like to desperately want to be able to do that, so I’m giving that to them.

Can you tell us more specifically about these characters?

Ryan: There are four characters, two guys and two girls, although when I first started writing it I intended for it to be more gender fluid so that any person could play any part. That would be true for future incarnations of it, if it were to be produced later outside of BOOM, this play allows for a fluid changing of the genders. The characters are named after the suits in a deck of cards. There’s heart, spade, diamond, and club. I’ll start with Spade.

Spade is somebody that I really think very heavily about because I think that at one time I was a Spade. The group approaching their six month anniversary of having been together, they’re all now living together, and it’s moving very quickly. Spade is the one who wants to throw more coal on the fire. Spade surprises everybody at the very opening of the play by having bought a very expensive sofa for the apartment that they share. Spade is a nest-maker. Spade is thinking long time, and talking about dropping out of grad school to go to work full time so that there is more money for this family. And I’m using the word family in Spade’s voice because obviously for Spade this is a family. Spade wants to have babies. Spade is looking into what state can they all get married in together. I think Spade is a character that is head over heels with this relationship but has a lot of fears and insecurities about it. Spade tries to resolve those fears and insecurities by moving things forward. This character has the best long-term vision of their group relationship out of anybody.

Is there a reason you’re not addressing Spade’s gender?

Ryan: Yep. Gender fluid. You’ll find out who they are when you see the show. So that’s Spade in a nutshell. Heart is a character that I see as an enforcer. This is very new to Heart, a poly relationship. Heart has done a lot of dating and is very familiar with what a non-poly relationship looks like and Heart is very comfortable with that. They know how those rules work. I think as the group came out of this mutual attraction and mutual love, Heart was the last person to be on board with it. And in coming around to it Heart has said, “I can do this but in order to do this I need to know what this looks like.” Heart was the one who set many of the rules of the group. Heart needs definition. If you cross those boundaries, if you try to change those rules, it becomes a losing battle with Heart. Heart is the enforcer. Heart looks out for everybody in the group. I think we’ve all definitely been a Heart and a Spade at one point.

Now Club is an interesting one. I think Club’s initial enthusiasm over the group is changing. I think Club has discovered that their love is not as poly as they thought it was. Club is learning that not all love is equal and Club would actually rather be exclusively with Heart and would like to change the nature and the rules of the relationship, even possibly ending it to be with Heart. But Heart is an enforcer and thus saying “that’s not how it goes, you can either shape up or ship out.” That’s in major conflict with getting the new sofa. Someone is moving this relationship forward and someone else is hitting the brakes really hard and pulling the E-brake. We set all these boundaries for a reason. In a play if you set a rule you have to break it, if you introduce a gun you have to fire it. Chekhov was good to me, I follow his logic.

Diamond is the last character. Diamond is a character that I have to be very careful when I talk about because I think that people will rush to judge them. Diamond has a hard time remaining exclusive to the poly group. I would ask audiences to give this character deeper consideration than this character is betraying the group. This character has a past that has informed the choices that they are making. This character is not out to hurt anybody but they don’t know how to not hurt the people around them. They make destructive choices for two reasons. One being that Diamond does not trust that any love that comes their way will last. Diamond is wary of love because love has been used against them in the past. This character has insecurities that leads to self-sabotage before someone else can kick them out.

These four people that started off as very close friends who realized that what they have could be something more, and this actually did come from a true place personally, they realize there is this mutual attraction and now they are trying to figure out how to make it last. What they are feeling is the greatest thing they’ve ever felt but it’s also the most dangerous thing they’ve ever played with.

What would you say has been the biggest challenge, knowing that you are not the show’s director and that this is your former company, in writing it and getting it onto its feet?

Ryan: I think coming from a director’s background I know what it’s like to work with a good playwright who is really a good collaborator and I know what it’s like to not have that luxury as well. I’m really, really hyper aware of crossing lines. Frankly, my process as a playwright in this has been to be there at the very beginning and give them the enthusiasm and information that they need and then walk away. Do my writing, get their feedback through the director, and then go away. I want to give them the free reign to go and make, go and create, to go and fuck it all up. I’m really okay with that. I want them to go and create. I think making is searching.

They need to be asking questions and I don’t need to be there feeding them the answers. They might find an answer in their production that I had not considered. I need to give them free reign to fail and to succeed. If I’m there as a safety net or as someone to feed them the answers then I’m limiting what they could achieve. It’s that awareness of stepping back and letting them do their work so that I can go do mine. I come back at the tail end to reinforce and support what they’ve done. But frankly I’m not the director, I’m not going to tell the director what to do with the play that I’ve written. I don’t think this play is my baby. I think a lot of playwrights do feel that. But this is not my baby. I am one of seven people working on this show. I do not wear a crown in that room. I sit in the same chairs as they do, I sit in the same circle that they do. We work together. I am no more of a valuable contributor than anyone else.

What would you say writing this piece has taught you about yourself as a playwright and as a human being?

Ryan: I think anyone who knows me knows that I was not raised to be an artist. I was probably raised to appreciate art. From a very personal place, I was not always encouraged to make art. In fact, I faced a lot of opposition growing up from my father when it came to creating art. He actually wanted to prevent me legally from going to college to study any sort of art or theatre. He actually threatened to sue any college that would have me. That’s one of many reasons why I haven’t spoken to him in ten years. For me, making art will always be a form of rebellion. It will always be me rebelling against my conditioning. I think being able to create and write a piece of work that comes from my own influence but is its own world that stands on its own two feet— that’s it not indulgent, it’s not an inside joke— people who have known this company for years they will love it and appreciate it. But for people who are new to the company this is a really good first play to see for the company.

I think it’s taught me that it’s hard work but I sort of realize that I’ll never get tired of rebelling against what I am supposed to believe about art and theatre. I never once considered myself a playwright until I think I started this company and started adapting works and then working on this piece. I have a new confidence in talking to young people about writing plays. I hate the phrase “if I can do it you can do it,” but hey, it fits. And I’m going to run with it. Just knowing that I can apply all of these skills— I can direct, I can perform— and take these things and make them work here, it’s a really exciting time to be working on this show.

What is the major conversation you are hoping people are going to be having with one another after they see Circle Circle Dot Dot?

Ryan: You know, if it leads to a greater conversation and respect for people across the gender and sexuality spectrum then I will be over the moon excited, thrilled, and fulfilled. I would love to see that happen. I would also love to see people across generations talking about love and what that looks like. I think that one challenge that the theatre field in general has is that they worry that older people want older art. I think they have a false idea of what older art looks like, or what attractive art to older people looks like. I think older people want to be challenged as well. I think they’re open to being challenged. I’m very excited to see how older people will respond to this play, particularly the baby boomers.

Why should people come out to BOOM and see Circle Circle Dot Dot?

Ryan: Who else is doing a play about poly relationships? This is something brand new. It’s not very often that we get to say we’re crossing brand new territory. I’m not writing another kitchen sink drama about a white family in upstate New York on the river that has a sad secret about mom’s pill addiction and now they’re so sad and they have to find something new to adapt their life. Shout out to Manhattan Theatre Club! But those stories have been told. They’re not new anymore. They appeal to a certain audience and there is a reason that people do them, and that’s because they know it will put butts in seats. But I don’t think that’s good enough. And I don’t think that honors why we’re here. It doesn’t honor the growth of the field, I don’t think it honors the growth of artists, and quite frankly I don’t think it honors the people around the art who are in the community. I don’t think it makes life easier for anyone in Maryland, I don’t think it makes life easier for anyone in general.

I think it goes back to my point that I don’t think art should be made for just pure entertainment. If I want entertainment I’ll go to karaoke night at the Metro Gallery. I won’t go to a theatre for it. I would love to see art that sparks a conversation or that sparks a debate. I want to see it spark new understanding.

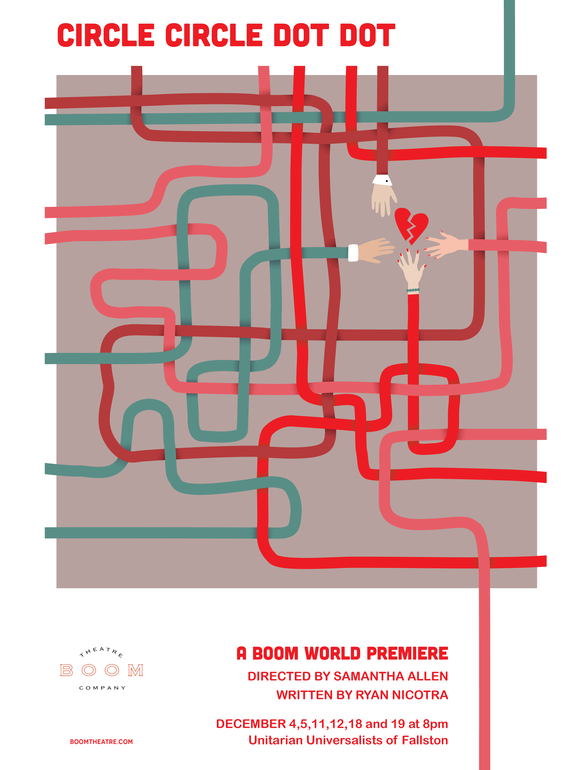

plays through December 19, 2015 at BOOM Theatre Company at the Unitarian Universalists of Fallston— 1127 Old Fallston Road in Fallston, MD. Tickets can be purchased at the door or in advance online.