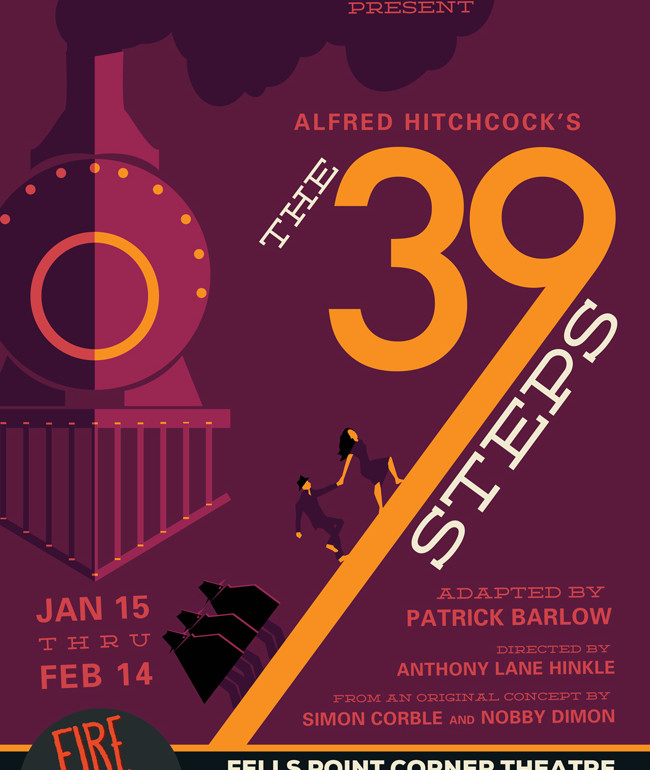

Ladies and gentlemen, with your kind attention and permission, I have the honor of presenting to you…well, I don’t suppose I have the honor so much as the Fells Point Corner Theatre and The Collaborative Theatre have the honor of presenting a lovely little farcical play on Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps. Adapted by Patrick Barlow to the stage in comedic fashion, and Directed by Anthony lane Hinkle, some two dozen characters grace the stage as four actors wittingly work their way through the dark and tangled plot of humorous proportions. With a decadent set, alluring costumes, and questionable accents, this co-production will entreat you to some truly rare performances worthy of a laugh or two.

The simplicity of the Scenic Structure is birthed as the brain child of Director Anthony Lane Hinkle. With the elegant red-draped curtain that is both fully functional and deliberately decorative, the set looks like it takes a step back into 1938, both here, there, and everywhere. The basic rolling structures of ladder frames and rotating doors lends itself to the farcical nature of the show’s intentions. Hinkle works cheeky little nods to other Hitchcock works into his design as well, like the house sign for Alt Na Shellach covered in the black birds from The Birds.

The problem in Hinkle’s scenic work is not in the design element but in the execution of the scene switches, which lacks consistency. There are moments where the active players make fully choreographed routines out of frantically changing the scenic elements— going so far as to peek at one another or pull faces with one another to acknowledge that the shift is happening too slowly or with some amusement— and these moments really work when they happen. However, not all of the scenic shifts are choreographed in this fashion and because of the non-uniformity these funnier bits feel somewhat out of place. This is a recurring theme in Hinkle’s overall direction of the show, as if he’s directing two separate concepts that never quite come together fully as one play.

Hinkle feels to be approaching the show from two perspective points— a shtick-laden campy farce and a serious thriller of a suspense play. But the shtick moments often feel as if they could be pushed farther into a grander plane of existence, and the serious moments don’t often delve deeply enough. There are truly exceptional moments that Hinkle crafts into the work— like the clowns acting as living furniture in the swamp scene— that would be extraordinary if they were pushed to a fuller extent of committing to the shtick-camp notions of their existence. The pacing, however, is extraordinary despite the lack of synchronicity between these two performances and never once does it feel to be lagging or dragging, even when the scene changes over exert themselves.

Other minor inconsistencies include the Dialogue coaching of Lydia James-Harris. For the most part there are strong hints of Scottish highland accents, and the main accent used for the Richard Hannay character is ripe and focused, but James-Harris’ other dialect work is often quite muddled. This only becomes problematic during the quick character switches, like those experienced by the clowns in the early train scene, switching from Paperboy to Salesman, Inspector, and Train Conductor, or in the Scottish bed and breakfast scene with the innkeepers and the hired thugs. James-Harris’ work is, for the most part, an added layer of amusement to the production, even when sounds get swampy.

Delivering stellar notions of light and darkness, Lighting Designer Kel Millionie brings elements of shadow puppet play into action throughout the performance, enhancing the humors of the show tenfold. Millionie also employs purposefully shoddy follow-spot lights for the humorous exchanges between Mr. Memory and his showcase manager when they are initially on stage. Millionie understands how to create atmospheric lighting without over-dramatizing and saturating the scene. His use of balance helps the audience move quickly from inside to outside and from day to night particularly when it comes to articulating windows up on the train.

Equally as impressive in their design work with sound as Millionie is with the lights, Sound Designer Brian M. Kehoe underscores the production to perfection finding exacting moments of humor and tension and juxtaposing them with ease against one another. Many a score clip revisited from various and sundry Hitchcock movies make their way into the performance and it becomes a delightful little Easter egg hunt of sorts when it comes to identifying just how many nods he succeeds in including. (A similar set of inclusions deserves a nod during the curtain speech as the clowns take turns trying to best each other as to who can squeeze in more references.) Kehoe’s soundscape burbles lively beneath the actions of the scenes and helps keep them moving, particularly during the lengthier scenic changes.

Though some of the quicker character flips between clowns Holly Elizabeth Gibbs and Steven Shriner are a bit clunky, when they settle into their solo characters there is a great deal of comedic genius to be had. Shriner takes to the role of Mr. Memory with a well-practiced routine, delivering the questionable performer with hints of folly that make one chuckle. His final speech as Memory is indeed memorable, as is his humorous bits as the milk-man early on in the performance. Playing the quieter of the two clowns, Shriner knows when to hold back and allow his scene partner to run the moment, showcasing a solid working knowledge of how to make a scene move as a pair.

Gibbs takes hold of several of the larger-than-life caricature characters and grips them firmly by the horns, refusing to let them go. This is especially true of her rogue Scottish farmer character and her villainous Professor Jordan. Though the accent switch on Professor Jordan is lost, what Gibbs lacks in dialect readiness she more than makes up for in enthusiasm and comic timing. Possessing a keen knowledge of how exactly to land hefty zingers, Gibbs makes her clown characters thoroughly enjoyable throughout the production.

Succeeding in the difficult task of playing only one character where everyone else plays many, Grayson Owen delivers a fine rendition of Richard Hannay. His concept of deadpan delivery is well-articulated, the wry sense of British humor radiating through his every joke and punchline. Watch Owen’s facial expressions closely as they are vivid tells of what the character is really experiencing, particularly when he’s dashing about seemingly confused. Owen plays well opposite Ann Turiano, the “leading lady” performer in the production. Their initial chemistry is quite volatile and Owen gives Turiano to and what for in the swamp scene quite soundly.

Turiano is a master of accents, moving from Russian, to quaint non-descript British, to meek and meager Scottish highlander, and back to the lovely 1930’s paragon of a British screen-gem ingénue. Her characterizations are distinct and unique, taking on only three roles by comparison to the dozen or so adapted by each clown, and her stage presence is dominating even when she’s playing a shy or timid character. The physicality that she brings to her women is consistently loaded with sensuality, especially when playing Annabella. Turiano has physical bodily responses when Owen brings vivid facial expressions during their exchanges at the bed and breakfast; they work together like a solid pair.

Ultimately an enjoyable evening, particularly because of all the insider Hitchcock nods, The 39 Steps is well worth the climb this January and will make an exciting conclusion to anyone’s evening.

Running Time: Approximately 2 hours with one intermission

The 39 Steps plays through February 14, 2016 on the main stage of the Fells Point Corner Theatre— 251 S. Ann Street in Fells Point in Baltimore, MD. Tickets may be purchased at the door in advance online.