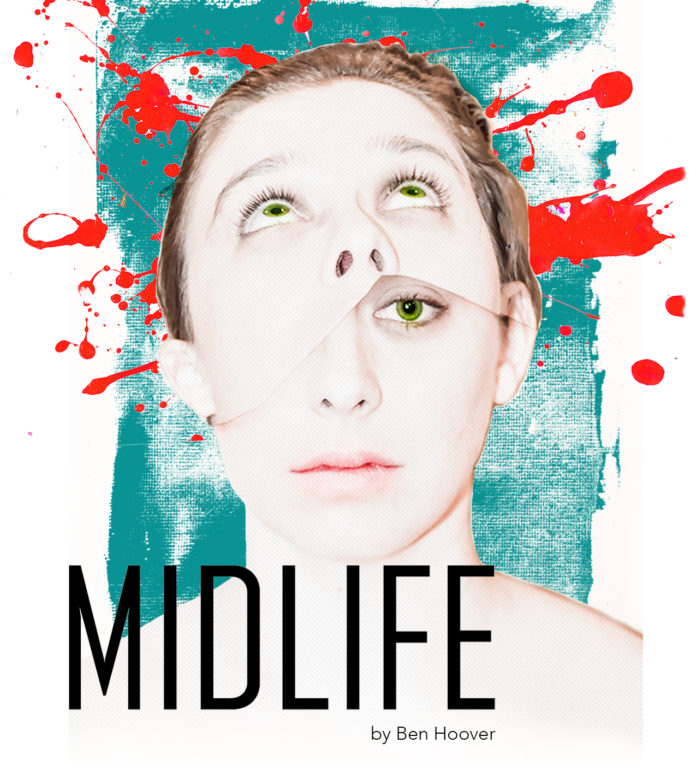

Life is slippery, like a fish’s tail. The harder you grab it the les of it you have in your hands. When life begins to slip away from your grasp, it isn’t always in the physical, tangential realm. What happens when the mind slips away from you? What becomes of your life’s story then? Are you two trains on diverting tracks tearing apart at the seams or are you an extraordinary fantasy fated for collision with the brutal harsh reality that is your mortal existence? Closing out Season 9: No-Fear New Work, Single Carrot Theatre presents the world premiere of Midlife, a new play by Ben Hoover. Directed by Kellie Mecleary, this emotionally disjointed yet poetically lyrical drama challenges the expectations of the mind and senses with persistent provocation of the mind’s inner psyche.

Playwright Ben Hoover’s new work opens a vast playground of conjecture and chimerical fantasy interplay in the worlds of Beck’s reality that transcend the traditional realms of life-plays and psychologically driven dramas. Director Kellie Mecleary takes things a step further off the beaten path by approaching the character’s internal monologue from a blunt and simultaneously infusive angle. The audience is given “innerlogue” devices (a basic headset pack) to wear for the duration of the performance so that every time Beck— the protagonist— expresses her internal monologue, it is piped directly into the audience’s ears as if they are hearing inside their heads what Beck is hearing inside of her head. This is a bold and unique theatrical approach to the work, which ultimately heightens the sense of intimacy and connectivity that the audience experiences with Beck and her ambiguous narrative.

Hoover’s words flourish with a poetic radiance. There are whole sections of vivid imagery, which falls lush on the ears particularly in the more intimate narrations. There is a great deal left open for conjecture and discussion; Hoover’s work as a whole galvanizes the audience to talk about everything from the blurred lines of fantasy and reality and how very close the two can be inside one mind to the potentials of mental disorders like schizophrenia, as well as mental degeneration like Alzheimer’s disease. The way in which Hoover juxtaposes perceived reality— in this case the fantasy of Beck’s internal experience— and actual reality— what’s happening around Beck as experienced by others— is striking. Mecleary’s blocking choices as well as overall framework for this play takes concepts to the next level, though provides the opposite of clarity when it comes to formulating sense from the narrative itself.

While Mecleary’s choice to use “innerlogue” assistance devices is a bold one— in so much that the experience is unusual and highly inventive— the execution is slightly less impressive as there is often a slight feedback or hum echoing with Beck’s speech, and although the offer to switch out devices is made at the top of the show, it seems impractical to do so once the two-hour play (without intermission) is underway. It is advised that audience members bring their own earbuds as the headphones provided with the devices are somewhat inferior in regards to the whole experience.

Composer Griff Beheler, Sound Designer Steven Krigel, and Lighting Designer Helen Garcia-Alton create elements of the performance that in a sense become a part of the work like shades of characters. The absence of light and sound throughout the production are as important if not more so than the presence, and the shadow play that occurs in the darker moments of light-in-absentia are quite profound to behold. Layering onto these concepts the Video Design work of Tom Cole is somewhat entrancing. The play delves into Beck’s brain, literally, and a projector screen highlights through an oval lens the world as Beck experiences it. This is another unique element that creates a very specific angle of experience for theatergoers inside Hoover’s work.

Props and Puppetry are designed by Jessica Rassp and are some of the most nuanced particles of the production. Without extrapolating in detail, for fear of spoilers, though they probably wouldn’t make much sense out of context, Rassp’s work is fictitiously phenomenal, especially her work with bloodied anatomy. The yarn-based puppets, both dog and shark, are somewhat mesmerizing to behold as well, blending into the reality of imaginative fantasy that is created inside of Beck’s brain, much like the circus the character envisions early on in the performance.

Scenic Designer Daniel Pinha takes the versatile space of Single Carrot Theatre and confabulates a remarkable hybrid set of reality and fantasy, both of which exist as believable play spaces. Pinha incorporates aerial silks, which are used both practically for aerial play and fantastically as vivid incarnations of the imagination, and gives them a natural feel whilst hanging free in the space. The use of the miniature cabinet of curiosities, which features heavily in Cole’s video work, is an impressive feature of Pinha’s overall design.

While the Homunculus ensemble (which includes Kaveh Haerain, Katie Hileman, and Elizabeth Scollan in addition to principal players who double up in this amalgamation of creeping creatures) is a curious concept that moves about shuffling bits of scenery and whatnot throughout the performance, it feels somewhat superfluous and the cross-contamination of having key players like John (Evan Moritz) V (Trevor Wilhelms) and Blue (Kaya Vision) double-up into those roles feels equally unnecessary. This is one of the only elements of the performance that does not feel as if it gels with the overall concept of the show, either textually from Hoover or directorially from Mecleary’s vision. Vision, early on as the circusiana character of Maximus, performs jaw-dropping aerial work that is worth noting in addition to his somewhat enigmatic character of ‘Blue.’

Genevieve de Mahy takes on the role of Beck with a fascinating approach to both the external character and her unyielding internal thought series. Her wild, often frantic narrations of these “innerlogues” are delivered with a heightened sense of urgency that borders on frightened, leading to the possible notions of paranoia or schizophrenia. But by the same token, there are blissful moments of serenity in de Mahy’s exploration of the text, all of which come tumbling through the headsets as something the audience can only hear inside the mind. Finding the delicate balance between these two states of existence, de Mahy does an exceptional job with mastering the text in a present and upwardly mobile fashion.

When the character of Ma (Claire Schoonover) comes into play, the dynamic between Schoonover’s performance and de Mahy’s is a compelling one to take in, the way they bristle, fighting for control of the inner monologue. There is something disarming but in a treacherously fearful way about the way Schoonover speaks, especially when confronting the character of Beck directly. It is difficult to further define their mesmerizing performances without forcing an interpretation of what happened between them upon the audience, and as this show is best experienced with no preconceptions of what their relationship might be, it can simply be said that they play their dynamic together with great vigor and intensely exciting energy.

Ultimately a thought-provoking piece of theatre, which is both visually and aurally stunning if not confusing, Midlife is perfect for sparking conversation about a myriad of topics that occur to people who live both inside and outside of their head. And in reality, don’t we all have separate lives existing inside our heads?

Running Time: Approximately 2 hours with no intermission

Midlife plays through June 26, 2016 at Single Carrot Theatre— 2600 N. Howard Street in Baltimore, MD. For tickets call the box office at (443) 844-9253 or purchase them online.