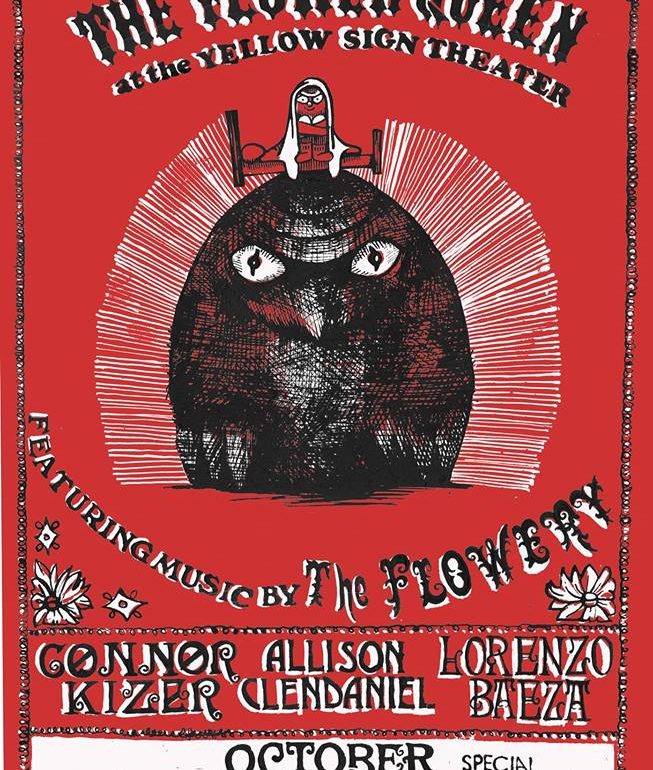

When you get into bed at night, you double-check beneath your bed to make sure there are no monsters, right? At least, you did when you were a child, didn’t you? What if there was a monster living under your bed when you were a child? And what if you made friends with that monster? Such a tale is what is unfolding at Yellow Sign Theatre in time for Halloween! A new play, The Flower Queen, written by Connor Kizer and Allison Clendaniel, is receiving its debut over the course of two weekends. TheatreBloom sat down with the creative minds behind the work to get the inside skinny on just what can be expected from the production.

Thank you both for sitting with us. If you’d like to introduce yourselves we’ll get started.

Allison Clendaniel: I’m Allison Clendaniel. I am a new music singer and interpreter. I went to school at Peabody so I kind of straddle a lot of worlds. I sing a bunch of Renaissance music, I do a lot of improvisation. I’ve sung with a bunch of different projects. More notably, I’m in a band called Nudie Suits. We have done a bunch of stuff around town. I’m really inspired by dismantled pop and slow-moving meditative kind of work, which is also what The Flowery— the band we’ve created for The Flower Queen— does. I really like all of these Buddhist traditions that my vocal heroes— like Meredith Monk— are inspired by. If you had pop music and took a lot of drugs and then tried to listen to it that’s what I’m trying to make. You should listen to it. Most recently I did the sound for Annex Theatre’s play Flatland. I’ve worked with them a bunch.

Connor Kizer: I’m Connor Kizer. I’m a WhamCity alum. I’ve performed with two bands in Baltimore, the Santa Dads, and The Creepers. And now The Flowery. I’ve done theatre with many outfits all over town. I’ve done a lot of stuff with Annex, a lot of stuff with E.M.P. and this is the third year in a row where I’ve put up a play that I’ve written myself. The previous two being Chronotony, at E.M.P., which was an endless loop H.P. Lovecraft play and then last year I did an adaptation of Michael Moorcock’s Behold the Man, also at E.M.P. Chronotony was in the basement.

This one is called The Flower Queen. How did it make its way over to Yellow Sign Theatre?

Allison: Well? We really like that space, honestly. I think that space has a really good magical energy. When you enter it, it has all of these amazing murals painted on the wall. Connor knows Joy (Producer Joy Martin) and it all just kind of enfolded really nicely for us.

Connor: I have a relationship with that space. I do an on-again off-again thing called “The WhamCity Lecture Series” a residual WhamCity thing, and I ran it out of that space for several years. I think we’re going to be starting it again— actually don’t quote me on that. So I have the working relationship with that space. And lately I’ve felt there is a sort of political thing happening in the Baltimore DIY Theatre scene. It feels like the energy is kind of congealing into this La Mondo project. And that’s great. It’s also a necessary part of growth. But me personally, I’m not into congealing. So I kind of wanted to step outside of that on this play, and Yellow Sign was a good opportunity for that. Also riffing a bit on what Allison said about the magical energy? Yellow Sign is haunted.

Creepy. And excellent. Tell us about The Flower Queen.

Connor: You want me to go first?

Allison: I think you should go first. This has been in your brain for a long time.

Connor: In terms of the way my projects work? Like looking at the last play, Behold the Man, that was only in my head for ten years before I got around to doing something with it. This play I first started thinking about in February of 2015. I was reading Robert Graves’ The White Goddess, which is very much a product of the 1940’s. It’s him talking about a poetic logic and trying to create a history using just poetry and mythology. And symbolism, particularly alphabets and Celtic alphabets. And Celtic tree alphabets and tracing those back to points of origin in Greece and common ancestors with Hebrew alphabets and stuff.

Allison: A lot of this “all time happening at once.” All of these myths have the same themes. That’s one thing that The Flower Queen is really pointing to. Most literally we touch on the Celtic mythology but I think that it’s about just how in any amount of time and space you’re existing in the same way that these ancient Babylonians were. It’s all the same experience. That’s what this art is sort of supposed to be reflective of.

Connor: It’s kind of making this argument that we draw these symbols from natural processes: seasons, the path of the sun, blooming of trees in fruit, etc., which create these stories that are then embedded into a collective human psyche. They inform all sorts of human processes that you just wouldn’t expect to find. It makes all these strange connections. I was reading this Robert Graves’ book while I was on tour with The Creepers. I would read just a little bit and then look up out the car window and every tree I saw and every letter that I saw written on every sign just unfolded into these weird mandalas of meaning. It was just a really mind-blowing experience for me and gave me the idea for this play.

Okay. But what is the play about?

Connor: Well, the elevator pitch is that it’s about a little girl who’s becoming imaginary friends with the monster under her bed, punctuated by ballets performed by the tree maidens. There are five of them, one for each vowel, and they are all performed by Lorenzo. (Ballerino Lorenzo Baeza.)

Allison: I also think this is worth mentioning. The alphabet is the first spell that you teach a child, which is a really heavy thing to lay on a kid because it controls the whole way that you experience language and communication. Engaging with these letters in a way that they are responsible for the things or making them mean more than just a shape on a page is what we end up seeing in this play.

Connor: One of the things that Robert Graves talks about is that the Celts weren’t really into written language. His argument, which we also have to acknowledge there is very little hard archeological evidence for these things that he’s talking about, is that he is not a scientist, he’s a poet trying to look at history from the point of a poet. And he’s working mostly from a Welsh standpoint. They don’t like written language, they’re really into memorization. It’s all about having it up in your head. Very similar to the Mentats of Dune if you want to get nerdy. We all want to get nerdy. My point is to that end, the way that you learn the alphabet— A is for apple, B is for ball, C is for cat…you have these associations that are drawn, which is a very Celtic way of learning and being able to internalize that information. That develops these— for a lack of a better word— code. Oghams. There are hundreds of oghams. A tree Ogham is what we’re using in this. B is Birch, but we’re using the Celtic names for them. There’s an ancient King Ogham, there’s a Flower Ogham, there’s a Crystal Ogham. Any way that you can encode the alphabet— like the normal Richard Scary way of learning the alphabet— becomes an ogham.

And then somehow music got involved?

Allison: Yeah. This is supposed to be manifesting in a dream. This should bring me back to one of the pieces of art I find to be most inspiring, Twin Peaks and Julee Cruise. You know how Julee Cruise’s music just feels like it’s this repetitive dreamy nature and you’re asking “Is this a song?” or “Is this a complete musical phrase here or am I just hearing one segment of it being repeated in my mind?” It’s beautiful but I can’t exactly make sense of it. That’s the big compositional inspiration for me. You’re walking through reality slowly and you may go back but then it changes and it shifts slightly. You don’t realize it. You’re hearing something but then you’re hearing a different something and you’re not sure how the in-between happened.

Each of the letters in the ballet are supposed to represent different periods of a little girl’s life. The first ballet is about birth, with water and there is this big nebulous feeling. The second ballet is about teenage years, fire and all that angsty feeling— there are a lot of bee sounds from the natural environment. Then— sorry, thinking about it not in it is really hard for me. The third movement is about motherhood and kind of the responsibility and the sexiness of motherhood and what that is in the steps towards completion of being a woman. E is this knowledge of old age and looking back at a life that is well fulfilled. And finally it ends— am I going to give this away?

Connor: This is the story of life. Everyone dies at the end of the story of life, so there’s nothing we can give away.

Allison: Okay, death. So the final ballet is about death. These ballets follow the life cycle of a matriarch.

Connor: We’re using two Oghams to structure the play. One is the tree Ogham. The meanings of the letters have associations with certain trees. It’s a play in five fingers because the way we travel through the alphabet there is a certain Ogham where every letter is associated with a joint. So that way when you’re sitting at the bar you can communicate by just pointing to different parts of your finger and it just looks like you’re fidgeting. There are five fingers so each vowel has a finger. The consonants structure the plot of the play, what happens next— and that’s what gives it a weird and dreamy feel. It also gives you this little kid feel. We move from one idea to another idea for no real reason. The root of the five fingers are the vowels. Consonants, in occultism, they give structure to the world, they’re more yang-y elements. Vowels, are the breath of language or the spirit of language. Music is the most sublime art form. It’s the highest thing you can study, it’s what structures the world. If you look at where the planets are in the solar system relate to how the notes in an octave relate to each other, they’re the same ratio.

So for our play the vowels are these tree goddesses, the signposts in the road of life.

You were talking a little bit about your process for creating the music, can you tell us a little bit more about that?

Allison: We formed this band, The Flowery. Our band is a lot of us playing with toys and me manipulating the sound through a modular system that I built on my computer. I guess it’s a lot of building loops. What else can I say about the music?

When you say toys you mean actual children’s toys?

Allison: Yes. We’re using an ocarina—

Connor: An Owl-carina.

Allison: Yeah, it’s shaped like an owl. We’re using lots of little toy maracas, there’s a cat toy in there. I’ve always felt like if there is a way to get a sound from any object— I’m really interested in that. This is an exploration of what do I have that makes sounds, what can I build with these weird sounds? Eric Spangler recorded most of these tracks at MICA. Did you want to say anything regarding your role with the music?

Connor: Sure. I think both with the theatre aspect of this play and with the music aspect, it’s focused around play and childishness. Our band was named by a five-year-old.

Allison: Yeah, our band was named by a girl that I watch. I said, “Ren, what would be an awesome name for a band?” And she said “The Flowery.” Just immediately.

Connor: That just coincidentally happened to go so well with the title of the play. A wise, wise child figured that one out for us. This element of play, the play is about a little girl who is supposed to be going to sleep and is not interested and then how she plays until she goes to sleep. It’s very much about toying and fun, which is why we use so many toys in our music.

You mentioned she makes friends with a monster under her bed. Is this any monster in particular? Is this coming from any particularly place in your psyche, in mythology, in history?

Allison: I think that it’s not any particular monster and I think that’s by choice.

Connor: I think he’s really an EveryMonster.

Allison: There is sort of an owl aspect to him because Blodeuwedd, who is the Celtic Flower Queen, she— Connor needs to tell her story because he has the proper knowledge— but she is an owl.

Connor: There is a book called The Mabinogion. In that book there is the legend about this guy— Lleu Llaw Gyffes— his mom has him and she’s angry that she got tricked into having him or something like that. So she refuses him all of his birthrights, she’s not going to name him, or let him get married. But then his dad or this friend of his dad is this wizard who keeps tricking her into giving him all these things. So to make it so that he can get married, the create this woman out of flowers, which is Blodeuwedd. But then it turns out she’s an actual person and she falls in love with someone else. So she ends up killing him. And then she has to run away so that she’s not killed by the wizard who created her for him— and there are elements of The Smurfs in here if you’re familiar with Smurf lore— but she turns into an owl and flies away. Her flight creates the Milky Way.

Allison: You know, people ask us what this play is about and we say the alphabet. And then they ask if it’s appropriate for children. There’s nothing that a child couldn’t see, but it’s not designed for children. It’s designed like a children’s television program. Like 1970’s Sesame Street. It’s designed to make adults feel like they’re children. I should also say that here in this interview we’re spitting out a lot of terms. And it’s hard to parse through all of that when we’re talking about the play? And it’s good to go in knowing that that’s there? But when you’re actually experiencing it, because it is written to be like a child’s program, it’s very simple language. If there is a part of the mythology that you don’t know— it’s there to make you curious about it— not to make you feel like you don’t know what’s going on. Everyone who has read the script feels okay with not knowing some of these terms.

Connor: People who are familiar with my work actually said that this is nowhere near as confusing as my usual work, that they didn’t have to stop and look up every other word.

Since you have a working familiarity with the denizens of Yellow Sign Theatre, how would you say The Flower Queen fits into the three pillars (1. Pop culture is older than you are 2. Low art can say things high art can’t 3. We exist to pull the stick out of the ‘high art’ artistic community’s ass) of YST?

Allison: All of those things.

Connor: After hearing you just rattle off the ‘mission statement’ I feel like I always thought their mission statement was “There will be blood.”

Allison: And there will be blood. But at its core what we’re doing here— there are all of these esoteric terms but none of that really matters because what you’re getting is the experience of a five-year-old. It’s like how you feel when you’re five-years-old and you want to pretend. You’re not confused, you do feel that you know these things.

Connor: It’s the rhythms of life.

Allison: Going back to what I originally said, it’s all of time existing at once and it doesn’t matter what pedigree you have, it’s that you’re living in this world and that’s all that matters.

Connor: And comparatively to pop culture, we already talked about the Smurfs, but in the ‘D’ section of the play we talk about the Lleu Llaw Gyffes story but then talk about how that’s just Theseus, The Minotaur, and The Labyrinth. Everything bleeds together. So yeah, pop culture isn’t new, it’s always existed, and it’s all the same. It all just boils down to the rhythms of life. You’re born, you mature, you have your own child, you die. These cycles are inherent in the processes that make up our entire universe and we just discover new incarnations of these same cycles over and over again.

What has been the biggest challenge with this project?

Allison: The thing that I’m most afraid of is getting people to know that it’s happening. Because we’re not doing it with an institution…it’s really hard to feel confident that folks will come. We made these little hand-written invitations, like a secret invite to a five-year-old birthday party. I mean I want everyone to know because I want everyone to come— but I want everyone to feel special. That’s the biggest challenge for me, now at this point. I’d say Connor and I also happen to be in love.

Connor: I don’t think that’s a challenge.

Allison: It could be. But it’s not.

Connor: Yeah I haven’t found it to be.

Allison: I find that working together with my partner on a project like this is just profound and special.

Connor: People have been asking me about that hoping to get some dirt or gossip. But it’s just been great!

What would you say doing this project has taught you about yourself, as an art-maker, as a creative mind, or even just as a human being?

Allison: For me I think it’s been incredibly empowering. My first venture into art-making, as a classically trained soprano, was being a vessel for somebody else’s work. I am doing the non-thinking, I am clearing myself, I am very Buddhist, I am just getting it transmitted. But for this, on every level of this play— largely the text was all Connor— but devising what works and what doesn’t work and making decisions with Connor and having to see it; then doing the music, and marketing, and tech, and putting out our album completely free of any record label, which I had never done before, doing everything by ourselves is just really liberating. I feel like I want to start my own country now. It’s also really good for making practical decisions— do I need this? Is this excessive? Being young and being a woman-identified person, I feel like you can feel uncertain about things that you’re doing, but this project has been very self-affirming.

Connor: Well, I guess I have very small challenges that I set up for myself? People were complaining that my last play was too long, it was over two hours. I like to respond to the critique that I hear from my audience, so I tried really hard to make this only an hour long, hold it to ten pages, and get rid of the long lists of ancient names that I generally like to put in there. I was just trying to have something that was less intimidatingly verbose and much more accessible. When I first looked at the script I said, “Oh, God, I failed at that.” And Allison has been a huge help with this, but it seems like the script is a lot more accessible than what I usually write.

Also, I think I’m a funny guy, but my plays are usually geared toward making you feel horrified. And although there is a horror aspect to this play, it’s clownish. There’s a lot of Marx Brothers in here. There’s a lot of Bugs Bunny, especially in the monster. There’s Abbott and Costello and classic Vaudeville comedy stuff in there and that has been a big learning lesson as well. Also? There’s no director. I’m used to being the director of a play and being able to stand outside and say “This is what it looks like and this is where we should be headed.” I’m not very into the idea of devised theatre because I think that objective directorial perspective is important. But this has been a devised piece. So it was a lot of me and Allison in our practice space, just doing it and having thoughts about it and wondering what it looked like outside of what we were seeing. These have all been huge learning moments for me.

You two are both performing in it?

Connor: Yes. She’s the little girl and I’m the monster.

Allison: And then the ballerina, Lorenzo.

Connor: Ballerino? Or Ballerina in man form?

Allison: Yeah, I think it’s Ballerino. That’s also been really nice about this piece. Devised work takes a really long time. We have the benefit of living together and being able to work on this for a really long time. One of our designers even said it’s really nice to watch because it’s like watching you guys play. And that’s really what it’s felt like for me. As a performer, this is definitely the most “in-my-skin” that I’ve felt.

Connor: I’m used to knowing that with this gesture I’m going to hit this mark, and I kind of come up with this dance of what the play is going to be like. But with this I’ve felt very free and loose.

Allison: We’ve never hit marks with this, it’s not about that. It’s how are we relating to each other this time through? So every time that you see this play it may be a little bit different.

What is it that you are hoping people are going to take away from seeing this show?

Allison: Can I put my marketing hat on for a second and say “a poster and one of our albums?”

Connor: That’s a good answer!

Allison: Really I just hope that they come away feeling entertained, welcome, and curious. I want them to talk to us, come over and have tea at our house, and talk about weird gods and goddesses. I want friendship.

Connor: And for me I have a much more egotistical occultist kind of thing. I want people to come away with more agency over the reality that they live in and take more responsibility for it on every level. I really believe that our perception of what’s going on is a thing that we have active control over and it structures the reality that we’re experiencing. Be the change you want to see in the world? I want that to be a completely different thing than a cutesy quote that you read on a meme on Facebook. That is magic and I want people to be able to walk away feeling like they now know how to be wizards and remake the world in the way that they need it to be rather than letting the world make them.

Allison: See the magic. You can feel less guilty for engaging with the Smurfs or whatever Marvel show is on. These archetypes are magic and they’re everywhere. You’re studying Greek mythology whether you’re aware of it or not.

Connor: And if you’re not making the world the world is making you. You have to get in there and grab it with your teeth and dance with it. I used to work in the science lab and I would have this horrible, emotional argument with the scientists. They would insist that reality was bottom up; the only thing that’s real is particles and ideas are a by-product of that. And I would say, “No. No! It’s bottom-up and top-down because particles create ideas which effect that particles, it’s a cycle!” It’s a circle and we have to accept that and dance with it in order to have a harmonious existence.

Why should people come to see The Flower Queen?

Connor: Here’s a good reason to go— it’s only ten dollars!

Allison: You should come to The Flower Queen because it’s the piece of art that I’ve made that I feel the most connected to. I feel like it connects with everyone in a way that is universal. I want to share this with people and I want them to share it with me. It’s a beautiful space that we can be in together. The message is about connecting yourself to the reality that you live in. My hope for everyone is that they feel grounded to the earth and their families and friends and that this will remind them of that.

Connor: It’s a Halloween magic spell that we can all cast together and grow as a community.

The Flower Queen plays through October 31, 2016 at Yellow Sign Theatre— 1726 N. Charles Street in the Station North Arts District of Baltimore, MD. Tickets are available for purchase at the door and in advance online.