Tale as old as time. Executing a Disney stage musical is always a tricky endeavor because one is competing with decades of iconic memories perfected and preserved in flawless animation. Even the best of the Disney stage shows suffer from the same stock problems: primarily easy to animate but difficult to stage scenes, added music significantly less stellar than the original scores, and inflated books from stretching the perfectly tailored 97-minute movie to two and a half hours of stage time. Linda Woolverton’s book does drag at points compared to her flawless streamlined screenplay. Composer Alan Menken’s classic score with his late partner Howard Ashman is intact and pristine, but his new music with lyricist Tim Rice is more often filler than substance. Add onto that the budgetary issues concerning elaborate costumes and sets. Charm City Players confronts all these pitfalls and, happily, succeeds with a charming production of Beauty & the Beast, directed by Stephen Napp with music direction by Kathryn Weaver.

Director Stephen Napp aptly coordinates a fine production, procuring both comic highs and a quiet heart as the piece fluctuates. His vision sticks closely enough to the film source, but reaches beyond in the new moments and in fleshing out a three-dimensional world for the characters. He develops a sweet and nurturing chemistry among Belle and the Beast, even amidst their initial bristling. He has guided his designers in creating this new universe, and his staging makes the scene changes, always a potential downfall of community theatre, fluidly flow with the story. Napp is also graced with captivating leads in the title roles, and Weaver who brings the rich, classic score to life.

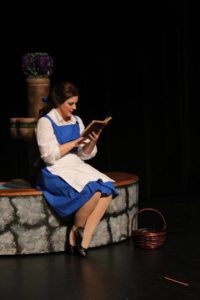

Emily L. Sergo, as Belle, handles the challenges of embodying a Disney princess with all the requisite grace and strength. A powerful vocalist, she understands where to pull back in Menken’s more operetta-like sections and where to soar in the new material. Sergo fares strongest with her two songs added to the stage version, especially turning “A Change In Me” (a number added mid-Broadway run to appease R&B diva Toni Braxton in her turn as Belle, and wisely retained for regional works) into an unexpected (and very necessary) 11:00 showstopper. As an actress, she lands the multiple facets of Disney’s initial postmodern heroine. Belle was the first Disney princess who took an active role in her story and an even more active interest in herself. She’s self-educated, refuses an inferior marriage proposal, sacrifices herself to spare her loving father, and chooses compassion for her tortured captor. Sergo finds all the nuances in these sometimes disparate emotions and situations, and transitions from outcast to gracious princess beautifully. In addition, her relationship with her father Maurice, an inventor who may be the original absent minded professor (veteran character actor Dave Guy in an unusually tender and touching performance), unfolds as a mutual expression of the characters’ love and protection of one another.

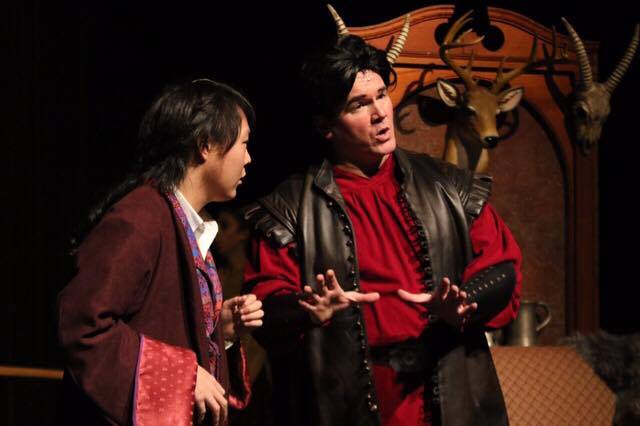

Lee Nicol’s Beast is a forceful match for Sergo’s fortitude. He volleys with her strong will in their sparring scenes, yet displays the Beast’s vulnerability and insecurity when in private. Abrasive and aggressive when Belle refuses to cower to his orders, he is never better than when he channels a decade of frustration and pent-up emotion into a vocally stirring first act finale, “If I Can’t Love Her”. Nicol expertly fills all the Beast’s heavy emotional and vocal demands, but there are instances when he falters slightly on the physical side. A diminutive actor of slight build, he camouflages his physicality well in collaboration with costume designer Sandra Boldman— between his iconic billowing purple cape and padded formal waistcoat that add extra volume and character potential to his performance. But inexplicably, he is directed to spend the bulk of the first act without his signature cape, and his Beast almost seems naked without it. These scenes are his most intense altercations with Belle and the staff, yet when he is sans cape, he also sacrifices a significant amout of the Beast’s animalistic intensity, appearing almost delicate. Minus the cape, he becomes too upright in his posture, too light of step in his walk, and too precise in his movement. There are instances where a costume enhances a performance, and this is absolutely one. With the cape he is an imposing force of nature. Without it, he is far less intimidating, a less beastly presence. It would be a simple fix for him to retain the cape and utilize it in his character the entire first act, as the Beast does in the movie (even the animators realized and made use of how much physical presence the cape and its billows alone possess to enhance, accentuate, and fortify the Beast’s body movement). Fortunately, this is resolved for the entire second act, and he transitions into a perfect prince in the finale.

The pair are supported by a competent corps of character actors as the denizens of the Castle, all likewise in various hybrid degrees of inanimacy. As his inner circle, Maggie Flanigan’s cook turned teapot Mrs. Potts is warm and maternal, and delivers a lovely, heartfelt rendition of the title song. J Purnell Hargrove as valet turned candelabra Lumiére is flamboyant and vibrant with a unique comic timing. He caters his Lumiére to his special comedic gifts, accenting the traditional interpretation with an additional contemporary layer of sass. He is the requisite equal parts Charles Boyer and Peter Allen, but by hilarious way of Titus Andromedon. His showstopper “Be Our Guest” is all it is expected to be. As butler turned clock Cogsworth, Gregory Quinn is the necessary stodgy straight man to Lumiére’s foolery, the voice of common sense and reason in a world devoid of it all. At this performance Quinn was having some microphone issues, and without amplification, his character tended to get lost in the lunacy of the other objects. A bit more vocal energy would counter this if it occurs again.

As the secondary tier of servents, Logan T. Dubel is charming as Mrs. Pott’s endearing son Chip the teacup, and Elizabeth Tane Kanner as former opera diva turned wardrobe Madame de la Grande Bouche has a personality as big as the cumbersome piece of furniture she wears. But Christina Napp as saucy French maid turned feather duster Babette steals virtually every scene in which she appears. She easily exudes a bubbly sensuality and brings out the best in Hargrove during their never-ending dance of flirtation. The French couple make a great comic team.

As the villain of the piece, the vainglorious peacock on steroids Gaston, Dean Allen Davis is cocky, arrogant, and of an explosive temper— all appropriate for a good Disney villain. He has the strong baritone necessary for Menken’s score, and understands the melodramatic ways of portraying an operetta. He is extremely fortunate, however, to have as his sidekick Christopher Lange. Lange (quite literally, sometimes) throws himself into the role of Gaston’s flunky LeFou, taking pratfalls, tumbles, smacks, slaps, and stage punches with split second timing. Some portion of the credit goes to Napp’s clever staging, but Lange is on board for the fun, sucks up the direction, and gives a no holds barred comic physical performance. The comic duo are at their best when milking their ale induced ode to Gaston.

The show is daunting to produce from a technical angle, but CCP enthusiastically attacks the challenge with great success. Costume designer Sandra Boldman deserves special praise for electing to build all the Enchanted Object costumes, and their transformed human counterparts. Focusing on the major players, she jettisons the enchanted egg beaters, vases, cheese graters and the likes, and focuses on enchanted silverware, parading follies dinner settings, and cancan dancing napkins to populate “Be Our Guest”, but the decision is allowable considering the sheer number of ensemble members she had to costume (over 70!). Her choices for the human characters admirably reflect their animated movie counterparts, and she preserves the looks of Belle’s iconic dresses and gowns.

Director Napp and stage manager Annmarie Pallanck perform double duty as set designers, and their talents not only provide maximum function by fluidly sliding sets in and out to enable Napp to seamlessly tell his story, but their work on the Beast’s castle deserves recognition for not only effectively fleshing out the various locales of the story–the library, the study, the dungeon, the west wing–in a visually interesting array of levels and thrusts, but the degree of detail and decor are exceptional. Their collaboration has produced a beautiful Louis Seize inspired castle interior, complete with gold leaf trim, gilded railings, ornamental fixtures and statuary, a bonus for any student of French architecture. And as if her onstage responsibilities were not enough, Pallanck also designed and painted an array of elaborate lifesize wooden cut out figures of all the featured movie characters to grace the lobby for atmosphere and photo opportunities.

Choreographer Jason M. Kimmell gets off to an unusually slow start with an atypically static and meandering open number in “Belle”, but his unique, talented touch is apparent throughout the rest of the show in a variety of fun, invigorating styles that range from a spirited syncopated mug routine in “Gaston”, a lively can can finale in “Be Our Guest”, and a sweeping Viennese waltz in “Human Again”.

With so many people doing so much right in concept and execution, there is one glaringly obvious question that needs addressed, the case of the Silly Girls. Did these particular Silly Girls, Gaston’s bevy of dim blonde admirers, do something to offend anyone? Because they inexplicably seem to have been abandoned by the entire production team across the board. The first and most blatant slight is their costumes. While the ordinary villagers are all dressed in varying looks of appropriate period attire, this specially featured trio wear spaghetti strap, above the knee dance dresses that look straight out of an H&M clearance catalogue. The palette is right, and these dresses could easily have been adapted with the addition of off-the-shoulder peasant blouses or even just sleeves, apronettes, and hemline extensions in a matching fabric. But as is, they are visually jarring and inappropriately contemporary in an otherwise true to period ensemble. (For the fashion naive, even lingerie would not feature spaghetti straps in 18th century France unless the wearer was a courtesan. And although in the original movie from less PC times, Disney initially billed the trio as “Bimbettes”, this look even stretches beyond the boudoirs of that moniker)

The rest of the show is so painstakingly costumed, it seems unfathomably out of place that this featured comic trio should be so oddly deserted. Then their solo sections in “Gaston” where they musically fawn over him were reassigned to other random townswomen, which makes no sense. On top of that, both in dancing and staging, there are stretches, particularly in “Gaston” where their unity is completely obliterated. The comic use of any trio is their function as a unit. Yet here they are straggled about the tavern, one occasionally draped on the object of their mutual desire with other random girls. Watch the movie–the three are inseparable. This is not just due to the theatrical law of three (even though that is more than enough of a reason), but because as characters, none of them would trust another with their man out of her sight. There are so many physical comic bits available with this trio, but very few of them were explored. Having virtually every element of their existence neglected, it is unfair to even critique how effective the young ladies are as performers.

But Silly Girls aside, overall, Napp and team deliver a very pleasant diversion into classic Disney fare featuring a winning array of vocalists who have teamed with a very talented production staff to breathe life and find the heart in the classic story. The sea of light-up enchanted roses (for sale in the lobby!) waved by little girls in an eclectic array of various Disney princess dresses is proof enough. Beauty and the Beast is a delightful opening production in Charm City Players current season of family favorite musicals.

Running Time: Approximately 2 hours and 45 minutes with one intermission

Beauty & The Beast plays through November 27, 2016 at Charm City Players now in residence at Mercy High School in the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Auditorium— 1300 E. Northern Parkway in Baltimore, MD. To purchase tickets, call the box office at (410) 472-4737 or purchase them online.