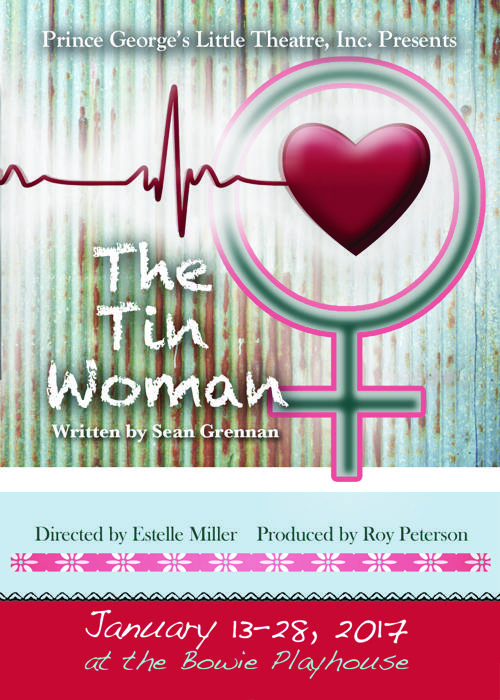

Live your life. We never know when it will stop. A fatal disease, a catastrophic accident, none of us know when life will stop. What if you had resigned your fate to life ending? What if you had accepted the fact that you were terminal when suddenly an organ became available to save your life? Would you want to know where it came from? Would you want to know whose heart was beating inside your chest? Could you bear the responsibility of life knowing your donor might have been extraordinary when you were just ordinary? Prince George’s Little Theatre takes a chance on a strikingly evocative drama, The Tin Woman by Sean Grennan, that touches the human heart in a manner most profound. Directed by Estelle Miller, this touching and emotionally charged theatrical exploration delves deep into the depths of the value of life, our purposes and persuasions, and delivers a riveting evening of theatrical engagement for all in attendance.

Director Estelle Miller keeps the setting simple. A few sparse furnishing, strategically placed with clear delineation between them to separate a graveyard bench, from a hospital room, from a tiny apartment, to a family dining room. With Property Designer Roy Peterson decorating both the apartment and dining room to authenticate a sense of being lived in, the realism of the play comes to the forefront of the show’s aesthetic. The true demarcation barriers of scenic shift and scenic design, however, come from Lighting Designer Garrett Hyde and Sound Designer Den Giblin. Hyde’s precision timing with sharply focused cues makes the transition from one space to the next quite fluid. Anchoring the production in space with subtle sound effects— quiet birds in the cemetery, a beeping monitor in the hospital room, an obnoxious door buzzer for the apartment— Giblin draws attention to the location of the play without intrusively treading upon the dialogue and plot development.

Miller’s overall pacing approach to the play is swift. It allows the audience to settle deeply into Joy’s narrative as well as the side-plots of Hank, Alice and Sammy, and how they fit into the grander scheme of things. Miller’s choice to make Jack’s character ever present and fully responsive is a smart one, giving an added layer of depth and dimension to every scene. The one misstep in Miller’s vision of the production comes from the spastic overreactions delivered by Sammy (Jenn Robinson) in the second act. In a scene that has the potential to be both touching and humorous, Robinson plays her over-the-top responses in such an absurdly caricaturized fashion that not only do they feel forced and full or artifice, but it makes the laughs that arise cheap and unsettling. This scene has the potential to greatly shift the dynamic among the other characters’ present, but fails to yield these results because it is played in an irreverent fashion. The audience would still find the humor in Sammy’s reactions if they were rained in and had more of an authentic sincerity behind them. To Robinson’s credit, her initial scene, is delivered with the perfect balance of quirky spunk and heart-heavy sorrow to create a beautifully balanced off-color character.

Brawnlyn Patterson, who first takes up the role as the elderly nurse— as indicated by her hunched posture, moseying shuffle and generally languid speech patterns— becomes a solid caricature in both roles. This, however, is an acceptable choice for both of her portrayals as the dialog for Patterson’s characters lends themselves much more readily to this vein of performance. Bubbly and bursting on the border of obnoxious as Darla, the edgy best friend, Patterson does deliver a healthy dose of well-timed comedic relief. Patterson’s keen understanding of how to properly execute comedic relief in an otherwise jarring and heavy drama is a welcome one; this provides her the depth she needs to communicate seriously with Joy over various matters without overplaying her humorous hand.

Alice (Barbara Webber) is the epitome of a deadpan delivery housewife, dipped in sarcasm and spun out to add a darker and more brittle layer of humor to the situation. It’s her quipping zingers fired back at Hank (James Estepp) that earn her praise with great consistency throughout the performance. Webber also demonstrates a tremendous sense of exploring and developing the character of Alice. Repressing her own tensions, sorrows, and other emotional expressions about the entire situation, Webber bursts out in a scene near the end that is both harrowing and cathartic to witness. When she hits that point of transformation, Webber delivers an astonishing monologue emblazoned with emotional uproar of feeling far too long repressed. This becomes a pivotal moment not only for her character, but serves as the catalyst that gets the powder keg lit for Hank’s lines of the story.

Estepp, as the aforementioned Hank, is a bitter and biting pill, particularly when it comes to trying to channel his frustrations and furies. There is an inconsolable grief present in his character, which Estepp carries deep in the pit of his gut, allowing it to fester away like a rancid canker eating him from the inside out. Every little escalation, every minute verbal outburst brings that purification of heart and soul closer and closer to the surface. The growling, snarling nips of conflict evolve rapidly into a raw, unabashed torrent of unforgiven rage, fueled by the deep anger and sorrow of the situational loss. Estepp’s most intense scene comes in one of Jack’s (Carlo Olivi)’s only spoken moments on stage. The pair goes head to head in a fully-charged, emotionally rattled shouting match and it strikes hard at the heart and the soul from both ends of the spectrum.

Olivi is a wondrous gift when it comes to being receptively reactionary. Much of Olivi’s time on the stage is spent observing, carefully absorbing all of the happenings around him. This ghostly presence, carried staunchly in the way he drifts through scenes, as well as in the way in which he uses his facial features to further express his feelings toward a scene. There is something convivial about Olivi’s performance, a naturalness to it that permeates the stage the moment he all but floats onto it. This serene sense of sincerity is catching and translates well into Zarah Rautell’s portrayal of Joy.

Emotionally dynamic and perplexingly versatile in the way she approaches the character of Joy, Rautell is a delight to watch on the stage. Watching her come to grips with her experience and her own life’s intentions is both harrowing and sobering. The way each realization washes over her, first across her facial features, then through a vocalization, and finally in her overall presence as if the fact takes a full and final effect inside of her, authenticates her portrayal immensely. There is an equally charged rawness in Rautell’s portrayal of Joy as there is in Olivi’s Jack and Estepp’s Hank. The three of them play exceptionally well together, despite most of Olivi’s interactions with either one being ghostly silent.

A truly remarkable play with so much to question, digest, and learn embedded deeply into a relatable family story, The Tin Woman is worth the trip out for the evening.

Running Time: 2 hours and 5 minutes with one intermission

The Tin Woman plays through January 28, 2017 at Prince George’s Little Theatre in residence at The Bowie Playhouse— 16500 White Marsh Park Drive in Bowie, MD. For tickets call the box office at (301) 937-7458 or purchase them online.