The gentlemen of the Sandy Spring Theatre Group (in a co-production with Arts on the Green) have spared you the experience of listening to a long and complex case wherein an ordinary man— a young man of no specific identifying qualities— is accused of brutally murdering his father. Twelve Angry Men, a dramatic rendering by Reginald Rose adapted from the television show of the same name, is a riveting play that will pull you to the edge of your seat and spark a conflagration of questions in your mind as well as your core values. Produced by Mara Bayewitz, and Directed by the insightfully perceptive Bill Spitz, this striking drama ensnares the audience’s attention early on, hooking them into a remarkably compelling piece of theatre for the evening.

Simplicity is the approach for the setting and overall aesthetic of the production. Director Bill Spitz, who also serves as the show’s set designer and costume coordinator (along with the cast), takes a basic approach to the production’s appearance and the result is surprisingly clean and effective. A jury room in that era— which could ironically be timeless because of the blanketed simplicity of the overall aesthetic— would not have been decadent or overly ornate in its existence. This bold choice of unadorned plainness speaks volumes of Spitz’ confidence in both Reginald Rose’s teleplay and in the cast which he has smartly assembled into each of their juror roles.

The production itself seems to arrive at a particularly poignant time for audiences quite close to the nation’s capital. With political unrest and uncertainty spiking to unimaginable peaks in recent days, the play itself takes on a deeper relevancy and bares a stronger message of justice than is intended by its mere existence. The intentional vagueness of Rose’s script, in regards to the young man on trial, is jarring. Nowhere is the young man’s race or ethnic background ever stated; it is only ever implied that he is not “one of us” wherein the ‘us’ is twelve men assembled of the jury. The broad scope of potential allows the audience to fill in the gaps, particularly when it comes to various lines, delivered with fully-charged hatred and prejudice— against this unidentified ‘them’— to a myriad of ostracized groups based on race, ethnic background, and even social class standing.

Spitz’ casting choices are sharp and perceptive. Utilizing Omar Latiri in the role of Juror #8 is just one example of the clever layered treatment that Spitz brings to the production as a whole with his directorial vision. The pacing of the production also moves exceptionally well, with Spitz pushing the cast forward through the argumentative scenes with rigorous gusto. There are moments that do drag, but they are intentionally scripted and exist with an authentic feel to them. Inspiring a profundity in each of the character shifts— as eleven of the twelve jurors go through a change of one kind or another be it minor major— Spitz has a sensational production on his hands, one the shows his passion for the subject and the play itself as well as drives home an important message of justice and responsibility.

The shared energy that the cast as a whole delivers is impressive. Keeping moments of riveting tension on a slow simmer until they’re bubbling over into catastrophic disaster is no easy task, but this core dozen performers does so with a practiced ease. It should be noted— as with all performances— that there were little flubs and slips here and there, but unless one has taken great pains to memorize line for line the exact wording of the script, this dozen gentlemen cover one another so well and share wholeheartedly the communal energy and drive of the drama that it goes virtually unnoticed.

Even minor characters, like the Guard (Robert Burrows), fill their parts. Though Burrows only trumps on and off the stage a few times, he fully embodies the dissatisfaction of his character’s menial position of employment. Juror #2 (Scott D’Vileskis), Juror #6 (Stan Rosen), and Juror #12 (Jason Damaso) fall on the quieter side of the spectrum but they have their moments. D’Vileskis delivers a particularly punchy line about cough-drops, aimed at the obnoxious Juror #10, while Rosen gets his moment later in the production, jumping up with great excitement— while simultaneously channeling a hint of Gomer Pyle— when things start to shift in his mind. Damaso’s shining moments are in response to others, particularly when the Foreman (Jim Kitterman) struggles to garner his character’s attention because #12 has blissfully tuned out into his own little bubble of existence. This callback between Kitterman and Damaso is quirky and entertaining amidst the gravity of the play’s otherwise serious nature.

Juror #7 (Marc Rehr) does a great deal of gum-flapping and complaining for the duration of the jury’s entrapment, prattling on about baseball with great gusts of annoyance coloring his delivery. Rehr has an unusual knack for creating a sarcastic energy and punching that sarcasm into the most unusual but highly appropriate moments. A bit on the edgier side, due to inexplicable youth, Juror #5 (Daniel Santiago) takes a similar approach only instead of sarcasm, he uses honest veracity and thin-skinned defensiveness to drive his character through moments of eager excitement.

On the milder and more reasonable side of the spectrum, though like the rest they all have their moments, Juror #9 (Rob Mostow) and Juror #11 (Phil Kibak) serve as voices of justified reason and reasonable justice. Mostow, who is one of the first doubters among the disciples of the jury, is both mild-mannered and determined. He, much like Kibak as Juror #11, finds understated moments to really draw the focus to their character in ways that fit the overall momentum of the production. Kibak deserves a nod for his German accent, giving him a pontificating professorial tone while Mostow’s patois is more akin to that of a county pastor. Both gentlemen deliver their lines in such a way that further clear the path to reasonable doubt that Juror #8 sets out to do from the onset.

With practiced patience, Juror #4 (Mickey Goldstein) maintains a level state of existence, never once raising his voice or erupting in a fit of apoplectic rage or fury. There is an unsettling calm with which Goldstein imbues the character that puts one uncomfortably on the edge of their seat wondering and waiting to see when he will snap and lose his mind or go completely wild. This cathartic bottle-burst arrives in a much different fashion than expected but is one of the most profound moments in the production, excepting only the jarring ending to the first act. There is a moment toward the production’s end, where a simple detail is brought to Goldstein’s attention and although he is silent, his face says everything. The way in which this information washes slowly and fully over his face is both harrowing and devastating and changes the entire tone of his character’s existence up until that point; this moment alone could be considered the defining pinnacle of the performance.

In a dead-heat tie for who boasts a more boisterous voice, Juror #3 (Stephen Swift) and Juror #10 (Bob Schwartz) practically start at the top of their volume, which makes it almost impossible for their moments of blind-rage shouting to be any louder, and yet somehow they both manage. Channeling such irate fury during their extreme blasts, to the point of coloring their faces red and purple, it becomes very frightening to watch them engaging in these moments. Though both characters are driven by a seemingly unnatural hatred, Swift’s juror falls more on the side of unsettled personal affairs projected into frustration while Schwartz’ juror is simply an arrogant jerk. Both Swift and Schwartz take great pains to create palpable depth and perceivable backstory in the character work of their jurors, Schwartz especially when it comes to the off-colored comments he spouts throughout the duration of the performance. A hint of an accent creeps its way into Schwartz’ performance as well, further authenticating the obnoxious and intolerant behavior of his character. When he hits his final monologue, it’s excruciatingly unsettling, forcing the other characters— and even some audience members— to look away in earnest revolted disgust.

Omar Latiri, as Juror #8, is the lead man of the production. Though not in the position of the foreman, whose job it is to conduct the jury through their decision making process, Latiri’s character becomes the guiding force and shining beacon of curiosity and hypothetical investigation. A matured and reverent Johnny Appleseed when it comes to sowing and tending the seeds of reasonable doubt, Latiri approaches the character from a rich and honest place. Delivering a strong presentation when it comes to his questions, Latiri hooks the audience and his fellow jurors, enthralling them with the notion that there might be more to a seemingly open and shut case. Masterfully mindful of both stage presence, textual delivery, and an overall sense of comportment, Latiri creates in Juror #8 the upstanding model of an American citizen, paying a nod of homage to Henry Fonda while creating his own unique approach to the character. Latiri’s portrayal is the definitive approach to how the character is meant to exist, even beyond the borders of the play in regards to how citizens of this great nation should act when the honor and responsibility of jury duty is laid upon their shoulders.

The timing of the production could not be more relevant. The production itself could not be more enjoyable. It feels perfectly balanced, it exists in a reality all its own and yet could very much be a real life scenario from today’s headlines. Sandy Spring Theatre Group and Arts on the Green have a fine production on their hands that should not be missed this January.

Running Time: 1 hour and 45 minutes with one intermission

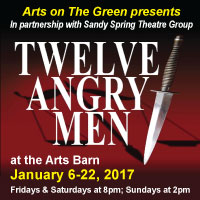

Twelve Angry Men plays through January 22, 2017 in the Kentlands Mansion & Arts Barn as a co-production with Arts on the Green and Sandy Spring Theatre Group— 311 Kent Square Road in Gaithersburg, MD. For tickets call the box office at (301) 258-6394 or purchase them online.