Die Bart Die! Probably not exactly what Kelsey Grammer thinks he’ll be remembered for when his time is up. Side Show Bob, that loveable nefarious evil-doer spawned inside the depraved animator’s brain of Matt Groening, father of the indomitable prime time animated series, The Simpsons. Of course, what will any of us really be remembered for once we’re gone? What about once the world as we know it is gone? What becomes important, what keeps people together, what prevents the world from stopping full-tilt when the power stops? When the electricity dies? What happens when the grid goes away completely and there’s no more power— do you think about the immediate fallout? Of how nuclear reactors at nuclear power plants like the one where Homer Simpson works in Springfield, will blow up, melt down, and destroy civilization as we know it? Probably not the first thought on most people’s minds if the power suddenly disappeared. (Unfortunately we presently live in a society where the #FWP biggest complaint would be ‘how am I going to do Social Media/Netflix-N-Chill now?’) Playwright Anne Washburn, however, addresses the nuclear reactor meltdown side of things in her evocative, albeit disastrously chaotic and deeply confusing, three-part script, Mr. Burns: A Post-Electric Play. Appearing now at Cohesion Theatre under the direction of Lance Bankerd, Washburn’s work closely examines what in our memory remains when it comes to pop culture and how we use that to restructure a future society once the world has come to an figurative end.

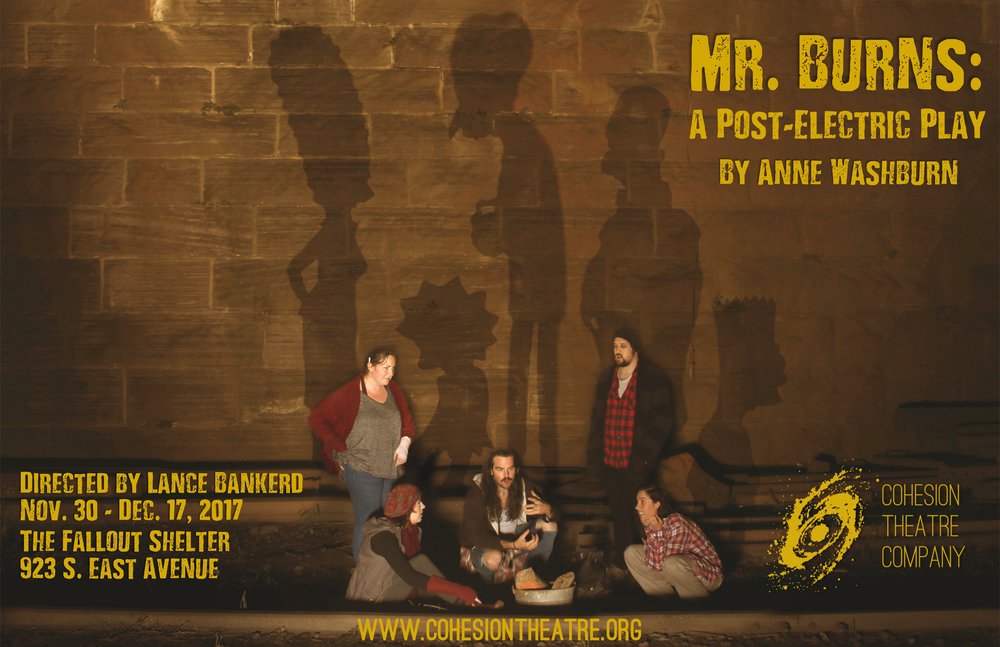

The irony that Cohesion Theatre Company plays in a Fallout Shelter (of the United Evangelical Church in Canton) is lost on no one when it comes to this production. Scenic Designer Jess Rassp takes full advantage of this and invites the audience into the fallout shelter as if it were the true end of the world. Director Lance Bankerd embraces the fact that Washburn’s work is essentially three different plays, with humungous leaps of time between each act, and works that into the gimmick of this theatrical apocalypse. Forcing the audience out of their ‘seating bunker’ at the end of each act (via creepy auto-recorded blaring announcements, almost like air-raid warnings, all voiced by Bankerd) so that the cast can reconfigure the placement of the staging space, helps the audience accept that they’re experiencing three different shows, even though the characters essentially remain the same. Bankerd makes full use of the space— starting with an inclusive campfire circle, which brings the audience right to the periphery of what’s happening with the performers.

As each act progresses, and today’s audience grows figuratively further from the time period in which the performers are working, Bankerd pushes the audience further away from the action. This symbolic stretch of audience inclusion furthers the isolation of a world forced to restart and evolve away from the one we know today. Taking full advantage of all the space and levels that the unique and intimate Fallout Shelter provides, Bankerd stages the first act dead center of the space with close-by seating, the second act of the show up on the physical stage (a first for any Cohesion production in this space!) with the audience gapped back to a respectable “fourth wall” distance, and the third up on the double-decker construct. This final staging space is both the furthest away the audience gets from the performers as well as being the closest; there are moments where these phantoms of what were once people from our own time ghost through the audience, right in the faces of audience members, haunting them like shadows and shades of the past.

A note of extreme praise goes to Lighting Designer Daniel Weissglass, for the insane amount of plotting and constructing done with the illuminating tactics used and featured throughout this production. Weissglass’ most notable achievement is the extreme low-light flicker effect featured during the first few minutes of the opening scene, wherein the audience is essentially submerged in darkness, with the exception of an inconsistently flickering dimness from above, mimicking and mirroring to perfection a dying campfire. There are other unusual and impressive lighting approaches which Weissglass uses throughout the performance, but that by far is the most eye-catching and memorable of the entire lit-up experience.

Bankerd’s separatist vision of Washburn’s work helps to make sense of the absurd time skips in her work. There is no salvaging or rectifying the nonsense that arises in Act III, but it’s written that way. Bankerd’s approach to it— with visually striking Simpsons masks hand-crafted by Tara Cariaso— gives the audience a sense of chilled confusion. The third act also requires the consultation of musician Mandee Ferrier-Roberts, as it includes an opera of sorts. Bankerd makes a cohesive statement with the piece, with the first act being logically sound much like any modern drama. The actors are driven with passion and a heightened sense of emotion; so too is the way of the second act, although with a great deal of skewed thinking in the dialogue and text.

While difficult to address the performances in the third act— though it has to be said that Nicholas Miles’ character is fierce throughout, even once he becomes one of Itchy/Scratchy (even I mix them up and I actually like/remember The Simpsons) in the pan-horrific opera that unfolds— the performances given across the board resonate from a place of truth. Miles’ character, Quincy, isn’t even introduced until the second act, but once he is, it’s a hoot. There is a natural flare delivered in the melodramatic re-incarnation of whatever it is that the characters are attempting to do in the second segment of the show (basically recreate from memory episodes of The Simpsons, with commercials are live performing arts troupes, like in the olden days of theatre tramps who traveled about!) Miles over the top theatricality feeds Chara Bauer’s bitter director character, Colleen, and gives the audience a laughing dynamic to chortle at until things get serious in a hurry.

Most of the character development, at least the bits integral to the plot, occurs in the first act of the performance. The aforementioned Quincy character is absent, but the others are present. Kathryn Hughes, who plays a silent character (watch the homage to Mrs. Krabapel in the third act) lingers around the campfire like an outsider, almost the reflective shadow of what the audience is in that moment. The unexpected arrival of Gibson (Matthew Casella) shakes up the group dynamic, which appears to be led by Matt (Jonathan Jacobs.) Watching the relationships that are exposed, unearthed and carefully cultivated between the opening act and the second act is a particularly intriguing thing, showcasing both the performer’s abilities and Bankerd’s ability to guide transition and evolution through large gaps in time.

Ultimately a rewarding, albeit at times confusing, piece of theatre, it’s not your average holiday play and thank goodness for that! It’s a play to make you think, to engage your mind, and at the holiday season when everyone else has switched off their brains in favor of saccharine Scrooges, sugary Santa’s, and that damn Official Red Ryder Carbine-Action Two-Hundred-Shot Range Model Air Rifle with a compass in the stock and this thing that tells time, Cohesion Theatre Company’s Mr. Burns: A Post-Electric Play will stimulate the senses and get you thinking just in time for the new year.

Running Time: Approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes with two intermissions

Mr. Burns: A Post-Electric Play plays through December 17, 2017 at Cohesion Theatre Company in the Fallout Shelter of the United Evangelical Church— 3200 Dillon Street in the Canton neighborhood of Baltimore, MD. Tickets are available at the door or in advance online.