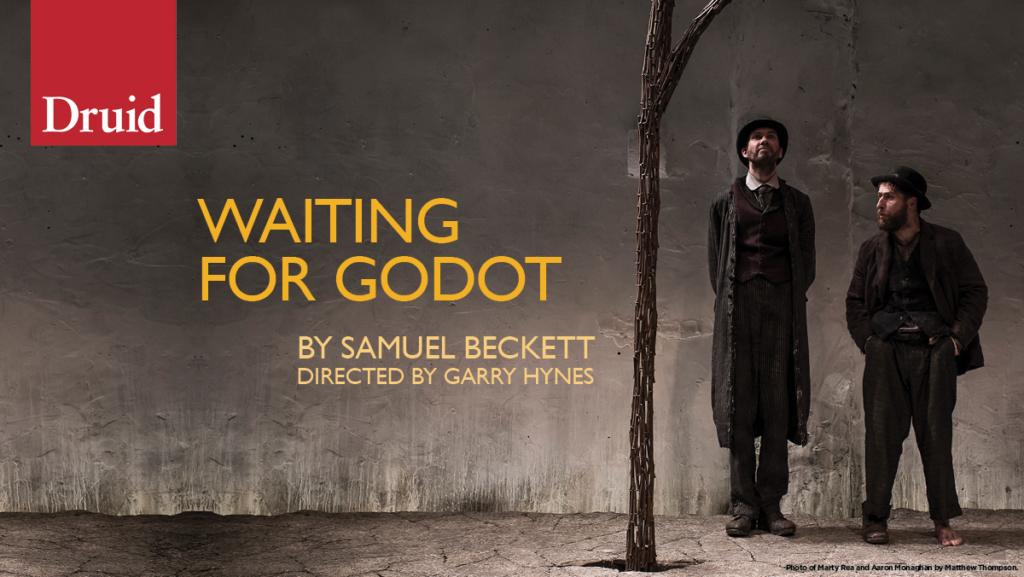

We are all born mad. Some remain so. But what is madness? The inevitable wait for that which will not come? The yearn of tomorrow knowing that it will never truly be tomorrow because tomorrow will always be tomorrow? Skipping Druid’s production of Waiting for Godot at Shakespeare Theatre Company this spring? That last one borders dangerously close on madness if not sheer delirium. Directed by Garry Hynes this classical reincarnation of Samuel Beckett’s darkly humorous and dreary drudgery of a drama finds reanimation and breaths of new life in this potent production presented by Druid.

Confronted with an ephemeral nothingness from point of entry, the audience is assailed by visions of a very tangible, barren wasteland. And yet Scenic Designer Francis O’Connor’s set design possesses an element of the surreal, of the absurd, of that which can only truly be experienced in dreams. The starkness of the sand-blasted architecture, the desolate nothingness of an almost blank canvas, the eerie stillness of the stage sets a keen sense of foreboding and gloom well into motion before the performance begins. Oft coupled with unique illuminations fabricated to fruition by Lighting Designer James F. Ingalls, and disorienting soundscapes that just breach the boundaries of reality as created by Sound Designer Greg Clarke, the atmospheric experience that O’Connor establishes is an extraordinary one. O’Connor’s designs unfurl further into the sartorial selections of the vagrant tramps of the play as O’Connor also wears the hat of the show’s Costume Designer.

While the pacing is on par with what is expected of the never-ending nothingness of a Samuel Beckett play, Director Garry Hynes cleverly disguises the passage of time through the rich and robust engagement of text amongst the actors. Assisted deftly by Movement Director Nick Winston, Hynes is able to draw the audience into the reality of Vladimir and Estragon, keeping them intrigued yet effectively on the outside. Hynes draws parallels to their existence for those in the audience without ever directly pulling theatergoers into the entirety of their world. This is a dizzying and yet fascinating approach to the work of Beckett. Expertly handling the weight of Beckett’s script, Hynes’ direction smartly transcends the multitude of layers of dark humor interlaced into the narrative, whilst balancing it against the severity of the situation and the overall story arc.

Winston’s movement work is at its finest and readily witnessed in Lucky (Garrett Lombard.) The physicality of the character sparks to life a certain humor, but the intensity with which it is carried out should not go unpraised. The mincing shuffle every time Lombard moves position is particularly amusing and equally impressive, as is the elaborate attempt at the dance routine which the character of Lucky undertakes. While Winston’s efforts are not exclusively focused on the motions of Lucky— with the ‘great hat-swap-scene’ of shenanigans being another prime instance thereof— there is no finer example in the production of his extraordinary capabilities than that which erupt from Lombard’s Lucky.

As the outspoken Pozzo, Rory Nolan does an exquisite job of expressing the character’s bombastic and outrageous nature. Carrying the nature of Pozzo with a strident air, Nolan embraces the put upon aristocracy as well as Pozzo’s vain sense of self-importance, channeling this into is speech patterns and his overall physicality. This creates quite the striking contrast when the Pozzo character returns to the place for his second visit. Watching the dynamic interplay between Nolan and Lombard creates some of the more humorous moments in the production, but also some of the most empathetic ones, as the relationship that they display is one deserving of much sympathy and pity.

Aaron Monagahn as Estragon and Marty Rea as Vladimir, or better known and referenced as Gogol and Didi, are quite the pair to experience in this iconic duo of stage partners. Playing their respective roles as if they could be two halves of the same split soul— a subtle layer of vision to the show as a whole as executed by Hynes’ directorial choices— Monagahn and Rea carry the show in as timely a fashion as such a play can be carried. There is an unyielding slowness at times, deliberately languid and intentionally torturous, as penned by Beckett; this pair handles it with superb charisma. They also take speed and haste when and where necessary to keep from delving past the point of no return into Beckett’s unending abyss of waiting.

Monagahn and Rea persist with vigor through the viciously maddening cycle of what they can and cannot recall, blathering endlessly about nothing, all the while managing to keep up an internalized sense of energy and importance. This is a masterful skill presented in equal parts by Monagahn and Rea and even in the quiet moments of stillness and still moments of quiet they manage to maintain a level of heightened intensity that drives the story and their existence ever forward. Both are equally matched when it comes to physical comedy, comedic delivery of speech and body, as well as leveling the balance of severity and gravity that comes along with Beckett’s work.

Druid’s production of Waiting for Godot at Shakespeare Theatre Company is rewarding and strangely satisfying, if disorienting and somewhat repetitively exhausting; the experience in itself at times defies description, though can most definitely be listed as one for the books.

Running Time: 2 hours and 45 minutes with one intermission

Druid’s production of Waiting for Godot plays through May 20, 2018 at Shakespeare Theatre Company in the Lansburgh Theatre— 450 7th Street NW in the Penn Quarter—China Town neighborhood of Washington DC. For tickets call the box office at (202) 547-1122 or purchase them online.