The sun on Columbia is summery warm. It’s shining on a theatre gem. So gather together and see their show. Tomorrow belongs— to them. Silhouette Stages mounts the production of the season— Kander & Ebb’s Cabaret as Directed by Stephen Foreman, with Musical Direction by Michael Tan and Choreography by Aime Bell. Truly not your momma’s Cabaret, this heady and intoxicating production doesn’t just showcase the darkness burbling readily beneath the surface of the iconic Kander & Ebb musical, it embraces it fully and exposes it wholly, presenting the audience with a high-octane political charge that strikes hard in today’s current political climate.

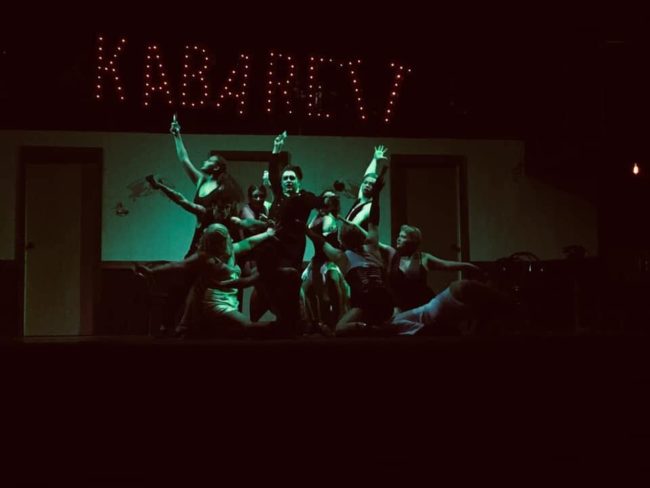

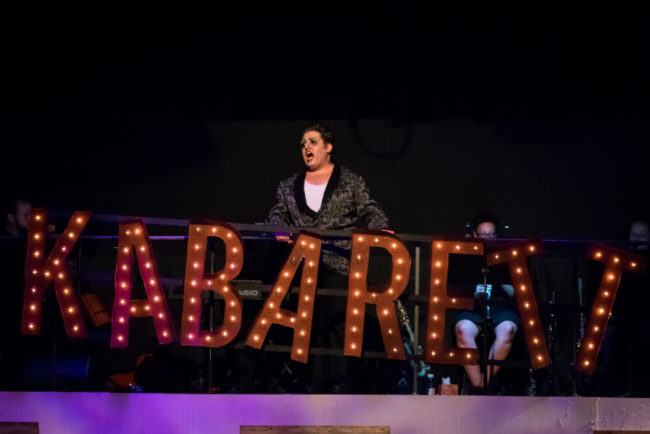

Willkommen! Have a seat right up front at one of the cabaret tables if you dare, it makes for a most entertaining experience, but truly there is no bad seat in the house with the way Director Stephen Foreman has outlined his scenic display. Working with Scenic Designer Alex Porter, the pair fabricate a duality of space that exists on one plane; the Kit Kat Club and Fräulein Schneider’s boarding house are one in the same but the way the actors and the furniture move around them, they feel completely different. Porter and Foreman have taken extra care in the preservation of details when it comes to the derelict structured façade that serves as the run of rooms in a hallway of the boarding house. The paint is water damaged, plaster is peeling up exposing brick, there is a tired feel to the set, which enhances the circumstances of the show’s location and cements its place in time. Foreman takes the aesthetic one step further, using the iconic frame-letters with bulbs atop the stage spelling out “Kabarett.” His intentional use of the German spelling showcases his dual purpose of the production, just as the word itself has two meanings. The first, simply being the German translation for the French word ‘cabaret’ and meaning as it does in English. The second being a satire devoted to severe political and social issues, executed heavily through cynicism, sarcasm, and irony. This is just one of many deeply original choices that Foreman sets forth in his vision of Cabaret.

Herein lies the tricky part; how does one discuss a great many of those aforementioned unique choices without completely exposing and or spoiling large plot elements. Both the Act I Finale and the finale of the show have a hard line drive to the show’s dark core message, which broadly speaking is the Nazi rise to power in Germany in the early 1930’s. Foreman doesn’t shy away from honing in on this element as other productions have done and will no doubt continue to do. There is a great, passionate drive in Foreman’s approach to much of the musical, both elevating elements of the show’s natural darkness and creating purpose, depth, and meaning in both moments and characters that are often dismissed or overlooked.

One of the most exquisite, discussable examples of Foreman’s work in this way is his construction of the “The Money Song.” While the number is humorous, featuring the Emcee at one of his zanier zeniths, Foreman seamlessly interweaves a scene we never see into the song. Cliff, on his initial errand for Ernst Ludwig, is trafficked through the dancers and the audience is exposed to his journey to Paris, retrieval of the briefcase, and exchange of marcs from hand to hand. It seems like such a simple thing to block, but in eight previous different productions (including one on Broadway) never have I seen this scene played in this manner.

Foreman adeptly hones in on little nuances inside Joe Masteroff’s script, which adds tremendous depth to characters like Fräulein “Fritzie” Kost (Linda Michele.) Fräulein Kost does have the dismissive and derogatory line about Herr Schultz’ being a Jew at the engagement party, but Foreman addresses the character’s blatant anti-Semitism scenes earlier, when Herr Schultz demands “…a little respect for the future Mrs. Schultz…” indicating that he intends to marry a German, non-Jewish woman. This provides a natural catalyst for her actions later. Foreman does not skirt around the disturbing elements of this production, nor does he try to dampen the heinous historical message that rings through it. Too many productions try to downplay these elements, trading on the show’s music and jarring conclusion to carry it through to being successful. Foreman means to open audience’s eyes to the full spectrum of tragically beautiful horrors this musical show is capable of presenting.

Musical Director Michael Tan, who leads the live, on-stage orchestra from a narrow catwalk above the stage, has his balancing act perfected. With a pit of just seven performers (Tan himself on keys, Tina James and Mari Hill on reeds, Tony Neenan on trumpet, Mike Allman on trombone, Jeff Eckert on bass, and Billy Georg on drums), well, the Emcee says it best. “Even the orchestra is beautiful.” Tan is impeccable when it comes to catching and giving tempo shifts to keep with the actors as they sing through their numbers. The sound of the roaring brass, particularly in the opening number, is lively and spirited, inviting everyone to a world where there are no troubles.

At first, the choreography that Amie Bell sets down feels disjointed and a hint of sloppy, but as it only read this way for the first few minutes of the opening number, it was difficult to tell if it was a case of opening night jitters that had the dancers out of sync with one another or if it was an intentional build of a cobbled-together club of derelict dancers down on their luck, pulling it together to do an opening routine, in a meta-break-the-fourth-wall-just-a-little sort of way. Bell’s choreography improved through the evening, particularly when it came to the high-energy kickline featured at the top of the second act, and the sexually provocative dances done on and around chairs inside the Kit Kat Club. The “Kick Line”, again under Foreman’s darkly guided vision, is thrilling and has the audience mesmerized, right up until it evolves from a spinning pinwheel of high-kicks into a stomping march of straight-leg thrusts, looking like a slow-spinning Swastika.

How in the world one gets costumes to look so filthy and yet so fabulous is anyone’s guess when it comes to providing the sartorial selection for Cabaret. Ask Costume Designers Clare Kneebone and Amy Bell (with an assist from Tommy Malek.) The pair pulled out all the stops for this production. Tawdry nighties and lacy pants, etc., all as expected for the Kit Kat girls and boys. It’s the array of stylish outfits— including some of the sinful selections seen in those Kit Kat nightclub moments— of Sally Bowles that really lets Bell and Kneebone put their mark on this show. The avocado affair is divine, one of her most celebratory looks and the dress in which she appears for the titular number is stunning. The pair craft masterpieces in their efforts to create sordid fashion pieces, and their look is polished off with Tommy Malek’s infamous wigs, and Kneebone’s designs on make-up, giving each of these unique characters a personalized look.

TJ Lukacsina’s lighting is pleasingly subtle. While there are moments of full stage wash in this color or that and a tightly burning hard-focused spotlight, these larger and grander lighting gestures are used sparingly, which makes them more useful when they happen. It’s the subtle hiss of green right at the end of Foreman’s “freeze-frame” of action (in the scene where Cliff has just agreed to go to Paris for Ernst to make money) that informs that number, rather than overpowering it as the music starts. Sound Designer Ben Kinder deserves several shouts for his impressively balanced microphones and use of special sound effects. Most notable is the smashing brick through the window (live-timed with the German Youth, played hauntingly by Gabriel Viets, throwing a brick down onto the stage from the orchestra pit catwalk ramp) and the roaring Nazi rally crowd sound that is used at a very particular moment in the production.

With a cast of just seventeen, every person makes their mark. The Cabaret Girls— Rosie, Lulu, Frenchie, Texas, Fritzie, and Helga (Felicia Howard, Briana Arielle Downs, Katie Jones, Miranda Austin Tharp, Linda Michele, and Lauren Romano) brings the dances in “Don’t Tell Mama” and “Mein Herr” to saucy, salacious life. Jones can be seen spinning some quick-step choreography alongside the Emcee in “If You Could See Her” while Michele spends her time mouthing off a great deal with Fräulein Schneider over wayward sailors. Michele takes up the backend of “Married” and although her voice quavers into a poppy-modern sound, her vocal intonation is spot-on for the number.

And then there are The Cabaret Boys— Bobby, Victor, Hans, and Herman (Angel Duque, Chris Weaver, Rew Garner, Nick Carter.) They add all sorts of sass and sin all throughout this production. Garner doubles up as the misogynistic Max, owner of the Kit Kat club and struts like he’s cock of the walk and knows it. They all play sailors, running made with lusty fever in and out of Fräulein Kost’s room. Watch Duque in particular at the show’s conclusion— his facial expression and body language perfectly displays the experience as Foreman intends the audience to absorb it. Though not among the Kit Kat boys, young Gabriel Viets dons a Swastika and joins the ranks of evil on the rise as the German Youth, accredited with singing “Tomorrow Belongs to Me.” It’s an eerie number, which sounds almost serene in the capable vocality of the dulcet tones that Viets produces, but when it’s full-length rendition— as heartily boasted out by Ernst Ludwig (Brad Davis) and Fräulein Kost (Linda Michele, who actually plays the squeezebox in live time)— ends the first act, it’s devastating.

The oft unsung hero of productions like Cabaret is the dialect coach. Most community theatres are often unable to produce one or hire one, but Silhouette Stages has procured Kelly Rardon, whose linguistics approach to the show was an overall enhancement. There are still one or two accents that waver here and there, but many of the principal performers— like Brad Davis as Ernst Ludwig and Pamela Northrup as Fräulein Schneider— deliver staunch German sounds that are still intelligible to the audiences’ ears.

Northrup is a force to be reckoned with in this production, both vocally and emotionally. With the previously mentioned consistent accent, which is just the right balance of thick and over-pronounced, she brings a staunch and grounded presence to Fräulein Schneider. Playing opposite the jovial and simplistically joyous Herr Schultz (Christopher Kabara), the chemistry that flourishes between them is delightfully saccharine and yet strikingly truthful. This languid development of trust and love and giddy sensations shared between Kabara and Northrup builds a tremendous hope for the characters and makes the show’s overall trajectory where the couple is concerned that much more devastating. When Northrup belts her way through “What Would You Do?” it doesn’t tug at the heartstrings, it tears violently at them. Plucking tenderly at the heart, Kabara melodically wafts through “Marriage” and when the two of them meld voices for “It Couldn’t Please Me More” you forget the silliness of the song’s subject matter and fall head over heels into their love. Kabara and Northrup do a lot of heart-impacting in this production, with Kabara being too stupid-cute for words and Northrup being so painfully honest that you feel dizzy and disoriented when all is said and done.

Clifford Bradshaw (Seth Fallon) is often the character that gets overlooked in productions of Cabaret. It’s not that he’s non-existent, as Clifford is essentially a plot construct that gives Sally a pit-stop and revolving point on her whirling dervish of a life, but rather that he falls to and is played in the background of Sally’s larger than life shadow. Director Stephen Foreman and the talented Seth Fallon take a surprisingly and refreshingly different approach to Clifford Bradshaw of Pennsylvania. Fallon is readily expressive both in facial features and with his body language. You could watch him chew scenery for hours. Watch him during Fräulein Schneider’s “So What?” number, every little reaction plays out across his face and its extraordinary. The same is true during Sally’s “Perfectly Marvelous” as he reacts and responds silently to this elaborate enigma that has just burst into his life. Foreman’s approach to Cliff’s narrative does not at all shy away from the closeted nature of the character; Fallon executes that flawlessly as well. And when he sings, for the brief moments that the Clifford character is assigned musical lines, it is glorious.

The Toast of Mayfair is Sally Bowles and the Toast of Columbia is Megan Mostow living and breathing as her. There is no right way to be Sally Bowles, but trust me when I say this that there is a wrong way. And Mostow creates a third category; she plays Sally her way. There is a curious presence about Mostow when she’s on the stage as Sally. It’s almost as if her Sally is fully aware of the fact that she’s living this fantasy life being somebody else, recognizing the escapism element of her own existence, and choosing not to ignore it but to fight harder for the escapism to be her reality. It’s fascinating. There is a giddy frivolity to some of her toss-aside lines (and good on her for chugging back that raw egg and Worcester sauce. BLECH!) but there is also a sincerity to it; it’s polarizing. Mostow possesses an insanely gorgeous lower register, vocally, which she accesses readily throughout this production. Sophisticated and yet sexy, blending the two together for “Don’t Tell Mama”, you get the tip of the iceberg’s complexity when it comes to Sally Bowles. One of the most fascinating moments Mostow presents is during “Mein Herr” because she is grappling desperately with Sally’s internal rage, and Sally’s own awareness of Sally’s escapism, and letting that internal war play out all across her face and body language while still belting her face off though the number. It’s indescribable. And forget about trying to find words for the way she slays “Cabaret.” The song lays down dead sung. Period.

If you’re looking for the carbon-copy Alan Cumming Emcee, go look elsewhere. There truly aren’t enough words readily available in the English language— and maybe there are in German but I don’t speak it— to accurately describe what Tommy Malek creates and becomes as the Emcee. If you strip away the “everyman/ever-present” nature of the Emcee, by not having him constantly hovering and double-dipping as the Train Inspector, prop-handler, etc., and you force him not to be a painted caricature echo of Alan Cumming, what do you get? You get this unimaginably vivacious and insatiable creature that exists both in reality and outside of it. And possibly under it. Malek’s Emcee is a spring-loaded jack-in-the-box who erupts at unexpected moments with cataclysmic explosions of personality— some furious hybrid between the actor and Divine mixed with insanity and intensity, and of course the makeup look of Pennywise painted up for prom. And that’s just the movement element of this fantastical, chimerical creation that Malek has fabricated in the Emcee. The vocal affectation is outrageous in the best way possible. But his singing voice, sweet Jesus, help us all. It will move you in ways that a character like that probably shouldn’t move you. “I Don’t Care Much” is a deeply disturbing ballad, not just because of everything that’s happening on stage, but because of the overall political attitude reflected in Malek’s vocal intonation, which is then headily infused into the lyrics. For the spastically zany shenanigans he brings to the character, especially during “Two Ladies” (a hilariously gay romp alongside Miranda Austin Thrap and Briana Arielle Downs), there is a harrowing balance of sobering depth that Malek brings to the forefront of the character. And you’ll have nightmares over his laughter and appearance at the end of the first act. A bit like theatrical heroin, you won’t be able to get enough of Malek in this role. It’s so very different and yet so very addicting and so very suited for the production that Foreman has set forth that it’s undeniably the best role Malek has performed in his Baltimore area stage career.

So? Leave your troubles behind. Because at Silhouette Stages Cabaret…everything is beautiful. And you won’t want to miss everything— even the orchestra— being beautiful, right?

Running Time: Approximately 2 hours and 30 minutes with one intermission

Cabaret plays through June 2, 2019 at Silhouette Stages performing at Slayton House Theatre in Wilde Lake Village Center— 10400 Cross Fox Lane, in Columbia, MD. For tickets, call the box office at (410) 637-5289, or purchase them online.