They say try and remember the good times, or think about the good memories, when doling out advice for how to cope with the loss of a loved ones. But good memories get ruined by grief; they make you wish you could forget entirely. What if there was no more need for forgetting? What if loss was no longer necessary? Enter Proxy, the last show on the Rapid Lemon stage for their 2019 calendar season. Making its world premiere, Proxy, written by Alex Reeves and Nell Quinn-Gibney, takes place in a none-too-distant future where AI technologies are allowing for the advancement of the basic human process of loss, more specifically how not to ever have to lose a loved one once they die. The harrowing realities and deep emotional potential of the script make up for its contrived and awkward dialogue; the overall experience is a thought-provoking one, because a large portion of the subject matter and overarching plot trajectory isn’t that far away from the reality in which we are living. Directed by T.P. Huth, this curious inquisition into the taboo realm of Artificial Intelligence creates a springboard for conversation surrounding the controversial topic.

The play itself is complex, weighted with loaded questions about ethics and morals and how they juxtapose against basic human emotions and existence. Playwrights Alex Reeves and Nell Quinn-Gibney have mined through the broad scientific field of Artificial Intelligence and found a focal point for their work and all the ideas are there. All of the questions the work evokes— like what happens to robotic AI that is so realistically human that it starts to function like a human once it has served its purpose? If an AI unit can upload emotional modules and simulations that allow it feel emotions and experience altered states the way humans do, are they still just AI-robots?— are powerful and potent topics readily up for debate in this rapidly evolving technological world. The script’s biggest issue is dialogue. Some of the dialogue feels natural, though distributed unevenly, and some of the dialogue feels contrived. There are moments where the trajectory of the characters is painstakingly clear, but the playwrights don’t quite know how to get from point A to point B and the result is a trite line or two that forces the characters forward. In places the dialogue feels unpolished, lacking in finesse, but the potency of the overall topic and the emotions carefully crafted into the work make it worth experiencing, and even help to forgive some of the larger dialogue-based misgivings.

Director T.P. Huth has gathered four talented performers and pulled forth raw emotions from them with exacting consistency throughout the performance. There are places where the pacing of the show just feels like it drags, but this is not any one pairing of characters or any scene in particular, but again falls to the writing of the dialogue. It just feels wordy in places, like expository details cropping up late in the second act for no other reason than being revealed, and character-development-based dialogue cues that should have arrived earlier (or are unnecessary because the actual performance by the actors and the costume, sound, and lighting design, fill in these gaps soundly) clogging up the fluidity of the play as a whole.

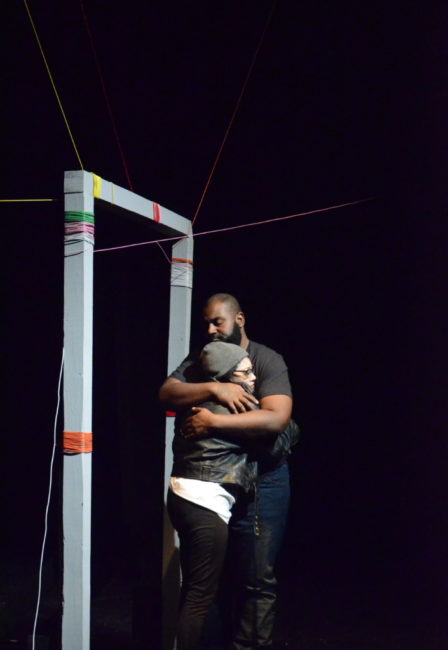

From a designer’s standpoint, T.P. Huth’s set is questionably artistic. It never became clear why the various colored strings (or tethers or cables) were twined all around the two doorframes, and whatever symbolism Huth intended them to represent remained lost in their hyper intricacy. The set was otherwise functional. Huth serves the script well by incorporating the brilliant creations of Projections Designer Judson Ridings and Sound Designer Max Garner. Much of the play has a virtual reality component, at least during the first act, and every time the characters are transported to one of these virtual experiences, a corresponding series of images (some mobile, some static) appear projected behind them, accompanied by a series of serene sound effects. Garner does a great job of bolstering the volume when the script forces the ‘sound effects’ of one of the VR segments to drown out characters who are bickering. Ridings, who gives us breathtaking views of a nostalgic lake house and majestic mountaintops, also gives us the constant reminder that we are dealing in the currency of Artificial Intelligence. Every time a scene transitions from one to the next, blinking binary code flashes across the screen, augmented by Garner’s technological soundscape.

The ensemble of four give a tremendous performance, often overcoming the dialogue-based shortcomings of the script. Their emotional fortitude and physical expressions convey what the words fail to, making the show a meaningful experience. Deana Fisher Brill’s costume design assists these performers in the visual identification of their characters. Kai (Ruth Elizabeth Diaz) is meant to be a punk-goth little sister strung out on grief and bad decisions, while Again (Rose Hahn) is a futuristic piece of Artificial Intelligence. Brill’s sartorial selections are the markers of these character traits, particularly in her use of silvers and grays for Again’s overall look.

Autumn Koehnlein spends the first act of the play actively dying as Kasa. (This isn’t a spoiler as it is made apparent within minutes of the show’s starting.) Her delicate, frail movements are telling of the condition of her character. Playing the AI-version of Kasa in the second half, Koehnlein is given more physical freedom, moving the way a healthy human being might move, with precision replication of her speech patterns and patois from the first act. Ruth Elizabeth Diaz, as Kai, goes through more of an emotional transition, though it is subtle. Going from moody and whiny to extremely volatile mood swings, Diaz homes in on the character’s stresses and grief and channels them accordingly. Noah Silas, as the rather standoffish Rennek, is an enigma on the stage. The character keeps close to the vest all of his feelings, and Silas delivers these struggles in what could be called a stereotypical male fashion. His character’s dialogue is the most contrived, and Silas should be commended for overcoming this challenge.

Rose Hahn plays the Artificial Intelligence Proxy, self-named Again. When watching her initial movements and listening to the way she speaks, one can easily be fascinated and almost hypnotized, forgetting that there is a bigger play and series of events happening all around her. The way Hahn speaks, just at the edges of being neither robot nor human, with hints of inflection but not any real depth to her expressions, is freakishly accurate to the way most people envision Artificial Intelligence. It’s even more scary to watch Hahn’s Again adapt and learn. The more modules the AI uploads, the more Hahn’s performance blossoms into something human. Watching the character experience happiness for the first time— not only for the first time but as her first emotion— is marvelous and spellbinding. When the glitches begin, it’s brutal to watch. Hahn’s portrayal of Again is arguably the most intricate in the production and really garners sympathy and empathy from the audience.

It’s a brilliant concept, much like a frightening episode of Black Mirror but with a deeper emotional bench and cruder dialogue. It’s a conversation starter and well-worth seeing. Proxy will give you a chance to support something new and local as well as delve deep into the questionable ethics of the quickly evolving technology of Artificial Intelligence.

Running Time: Approximately 2 hours with one intermission

Proxy, a Rapid Lemon Production, plays through October 20, 2019 at The Baltimore Theatre Project— 45 W. Preston Street in the Mt. Vernon neighborhood of Baltimore, MD. For tickets call the box office at 410-752-8558 or purchase them online.