Right is right and right don’t wrong nobody. A strong decry of truth and justice in a time when its sorely needed; to think such words originated from August Wilson just 14 years ago (taking place a mere decade before that) in Radio Golf, the last in Wilson’s Century Cycle play series. Now appearing on the main stage of Everyman Theatre as the second dramatic offering in their 2019/2020 season, Radio Golf, Directed by Carl Cofield puts social justice and racial inequity under raw scrutiny for everyone to examine.

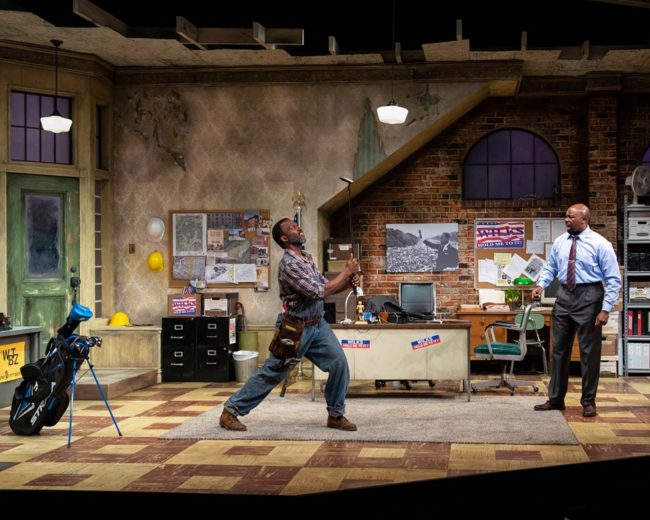

Set Designers Christopher Swader and Justin Swader have crafted together two concepts for the staging of Radio Golf. There is the progressive, albeit cluttered, political campaign office of one Harmond Wilks and the old construction office, which is little more than a derelict crumbling, albeit historically preservable, structure with all of its tin foiling and intricate design work on the ceiling. Swader and Swader bring these notions together, figuratively and literally, under the same roof (with the little bits missing and decaying before everyone’s eyes) when Harmond Wilks’ office settles into the aforementioned space. Exposed bricking meets motivational posters (and catchy bumper stickers in the second act) all while still possessing the feel of being in an unsavory neighborhood.

Right from the play’s start, August Wilson informs the audience (as all of his dramas do) that the play is structured around social classism and racial conflict nestled deep within those class constructs. Mame Wilks, the wife of the hopeful Mayoral candidate, even says that TV crews only come “up the hill” if there’s a shooting, painting the clear picture early on that the neighborhood in which they are is clearly unsafe, run-down, and plagued with urban blight. Wilson’s work is riveting in that regard, forcing the audience to examine the difference— and whether there is one— between restoration of a poor, urban blighted neighborhood and the gentrification of one. Is it still “bringing back the neighborhood” even if the person of color organizing the plans intends to knock down all the eyesore housing, build high-rise condos, and bring in a Whole Foods and a Starbucks? Or is that not gentrification because of who is proposing and funding the project?

Where Wilson’s work gets muddled isn’t in his fabulous characterizations or his intensely loaded racial tensions (even though every character in the play is scripted as a person of color) but rather in his loose tie-in with golf. In the grander picture, particularly with the politically potent relevancy of the play to today’s current political climate, the overarching theme and tie-in of golf feels contrived, almost as if Wilson forced it into the work, detracting from the bigger issues at hand. Perhaps in a different time or a cooler political climate the golf references and tie-ins wouldn’t feel so contrived.

Director Carl Cofield keeps the production clipping along briskly. August Wilson drama’s are not noted for their brevity, but this one is an earnest breeze with Cofield directing and the talented cast that has been selected. Dawn Ursula, whose character of Mame Wilks is featured only briefly, really presents the earnest struggle that the characters of color in this production face when they try to raise their position, particularly in political circles. Her passions are earnest, her furies are raw, and when she brings the argument between her character and Harmond to a head, it’s brutal.

Harmond Wilks (Jamil A.C. Mangan) is the central protagonist, around whose viewpoint the story revolves. He wants to be the first black mayor of Pittsburgh. He has enormous dreams for revitalizing the urban-blighted Hill District. Mangan has a deeply soothing voice, which helps when some of the words that come out of his character’s mouth start to sound less than desirable. And while he is indeed a presence and a focus on the stage, and the ultimate outcome of the show is his own trajectory and plight, it’s the two intense characters around him whose stories are utterly fascinating.

Sterling Johnson (Anton Floyd) and Elder Joseph Barlow (Charles Dumas) are pure salt of the earth, larger than life characters, that one can marvel over for the course of the entire production. Dumas’ Elder Joseph character sucks up every breath of air in the room in the best way possible, even providing a great deal of humor and moments of relief during scenes strung taut with tension. Floyd, whose character is essentially the younger, more vivacious version of what Elder Joseph has become, is radiant and vigorous every time he pops onto the stage. The pair present intense moments of serious and evocative concepts that drive the show forward to its intense conclusion. And they do all of this in spite of the rather vicious and haughty edges of the Roosevelt Hicks character, played with welcomed rigor by Jason B. McIntosh. There isn’t an antagonist in the production, per say, at least not at first. McIntosh’s character is obsessed with getting his seat at the table, showing how easily one can flip sides to maintain one’s position. McIntosh plays well the rather sketchy characteristics of the Roosevelt character, bristling just fine as a foil for both Harmond Wilks, Sterling Johnson, and Elder Joseph.

With such a contained cast, these five performers serve August Wilson’s words extremely well, even the ones about golf, which often feel tangentially adjacent to what’s actually happening (almost like they came from or were intended to be a part of a different narrative.) Ursula, Manga, McIntosh, Floyd, and Dumas deliver a stellar performance as the five characters in Radio Golf, which despite its golf-focus, is extremely important for today’s audiences in this political climate.

Running Time: Approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes with one intermission

Radio Golf plays through November 17, 2019 at Everyman Theatre— 315 W. Fayette Street in the Bromo Arts District of Baltimore, MD. For tickets call the box office at (410) 752-2208 or purchase them online.