Rivers run where they can ramble…and theatres find stages where they can produce. The Fredericktowne Players, who are extremely grateful to be producing at The Weinberg Center for the Arts in downtown historic Frederick, are launching their limited run of Pippin for one weekend only. Directed by Matthew Bannister, with Musical Direction by Matthew Dohm, and Choreography by Laurie Newton, this musical theatre production goes beyond the dreams of running away with the circus and presents a refreshing, albeit complex, new focal point through which to view the narrative of Stephen Schwartz’ work.

The show Pippin has a certain appeal; audience members of a certain age who were around for its Broadway debut in the early 70’s or those who more recently remember the ‘high-circus’ façade slathered over the mid-20-teens touring production are the ‘cult following’ of the show. Both will find entertainment and enjoyment in Director Matthew Bannister’s framework of the Fredericktowne Players’ production. Even if you are unfamiliar with the show (google it, we all know you know how), the level of talent contained within this production far exceeds that of ordinary community theatre and the overall experience will be an enjoyable one, even if larger parts of the show’s concept are lost on the average layman.

Bannister has conceived a framework for Pippin that can only be described as ‘theatrical catnip’— a show appealing primarily to musical-theatre nerds who have a deep resounding understanding and appreciation for both the genre and Pippin itself. (Again, please re-read the previous paragraph if you’re worried about your lack of understanding or experience with the show impacting your ability to enjoy this particular production; it won’t.) For those unfamiliar with the broader scope of Pippin, one of the components is the “play-within-a-play” notion; Bannister locks onto this as his framework for the Fredericktowne Players’ production and blurs the lines of modern reality, stage life, and the narrative of Stephen Schwartz’ work in a dizzying but dazzling fashion.

For those seeking the circus, elements of that high-octane entertainment are still liberally peppered throughout the production. Costume Designer Stephanie Hyder’s work is where this is the most evident. The dance-corps ensemble (which to me are strikingly reminiscent of any PhantomCorps from Rocky Horror both in their movements, body language, and overall stage presence, not to mention the way they pop out of the floor without warning) wears shades of red, black, white, and gold, with crisscross tight straps, and face paintings all of which allude to the circus without ever directly transporting you there. One might say Hyder’s sartorial selection could be a subtle homage to the show’s circus beginnings. The most spectacular costume piece featured in the production is the outfit seen on Lead Player, which is a combination of black and white tights, boots, (or shoes depending on the scene) and shimmer tops and skirts, split down or across the character’s body, a conspicuous representation of right and wrong or good and evil. Hyder also deserves props for the saucy dress seen on Fastrada and the ‘flapper girl’ couture used to highlight Berthe.

Set Designer Heather McFadden keeps the scenic design simple but not in a lackluster fashion. There are columns and archways, which help the audience remember that Pippin has factual roots in history (being the son of Charlemagne). But there’s also a bed, which doubles up as a throne, conveniently conceived by McFadden’s use of flying scenery, both backboard and throne back fly in and out when the scene changes demand it. Complimented by the work of Lighting Designer Lindsey McCormick, Hyder’s set takes on a life of its own during more intensely emotional moments of the production. McCormick, to her praiseworthy credit, does a spectacular job with all sorts of lighting effects which imply a whole host of things throughout the performance. There is a balance of ‘party lighting’ during the high-energy group dance numbers and ‘mood lighting’ featuring blues and purples (and occasionally demonic reds) for more sobering sections of the story, but the true sparkling gem in her crown of illuminating achievements is the ‘fire down below’ effect, which is seen first during an early ensemble number and again later at the show’s conclusion. McCormick uses the orchestra pit and lights from below, creating a striking and haunting lighting effect of fire burning up from beneath the stage; it’s terrifying!

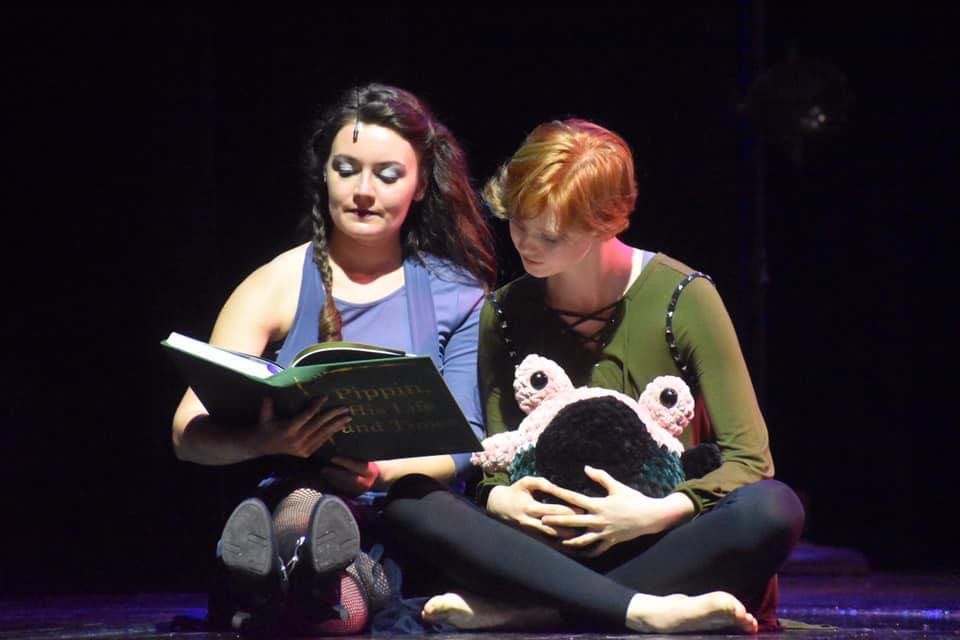

Director Matthew Bannister, as previously mentioned, has crafted a framework around the story of Pippin. He homes in on the concept of the ‘play-within-the-play’ and makes that the narrative reality for Theo and Catherine, who are merely experiencing the story during Act I as if it were a bedtime story (complete with oversized prop book) being read to Theo by his mom, Catherine. Bannister does a brilliant job of taking little moments and having the Catherine-Mom ‘read aloud’ dialogue (a line here and there that would otherwise be delivered by the player, who is still on stage, active in their scene and moving their lips as if speaking) to Theo. This cements the notion that everything we are watching is a part of this grandiose bedtime story called Pippin. There are even hilarious reactions from Theo; when a scene gets too romantic Theo starts mock gagging and walks off stage or when something inappropriate happens, the Catherine-Mom tries to shield Theo from seeing it. There are even moments when Theo joins in the motions and dances of the other characters, illustrating the way a youth might imagine themself as an active part of their bedtime story.

All of those conceptualizations lay the groundwork for Catherine and Theo, who become players in the actual play in the second act, to realize what’s happening. (Pippin is a complicated show. Google it. We know you know how.) There are even more moments of connectivity that thread this concept together during the second act of the show, but to members of the audience for whom Pippin is not a well-known (or never before seen) experience, such moments may feel slightly incongruous or feel confusing. They don’t ultimately detract from the production in a way that leaves you feeling frustrated with their existence should you not understand why they’re happening. Such moments include “Pippin in Memoriam” flash segment during “Love Song” and the entirety of the staging and execution during “Marking Time.” Its not to say these moments are brilliantly crafted and exceptionally clever; it’s just that they aren’t going to land with every audience member. What becomes slightly confusing, and perhaps a layer too far, is Bannister’s inclusion of all of the war graphics in the background during select scenes and numbers. While it’s obvious, even to those that don’t know the show, that this is symbolically reflecting the chaos of Pippin’s world with that of actual reality, it feels somewhat superfluous in the sensory overload department. It’s a choice, Bannister commits to it, but at times (particularly when showing the Twin Towers and the lit memorials that have succeeded their place in the Manhattan skyline) it feels overwhelming and pushes things a little too far.

Choreographer Laurie Newton seems to have magic to do in her own right, with several of the scenes requiring a censored hand when it comes to execution. (Pippin at times is not necessarily meant to be for the feint of heart…or those under a certain age.) But the more ‘exotic’ scenes are handled tastefully and PG-14 in Newton’s hands and her overall approach to the show’s choreography is clean and simplistic but highly stylized. The movements fit the music. Dancers worthy of note include the sensual ballerinas (Kiersten Gamsey and Jillian Mullin who parade around with Pippin in a most evocative fashion during “With You.” Newton uses the emotional flare of various musical numbers to inform her dancing ensemble’s movements and balances this against skillset, stage space, and the overall style of the song.

Musical Director Matthew Dohm achieves sonic brilliance with the ensemble coming together for powerful renditions of “Magic to Do”, “Glory”, and “Morning Glow”, with the latter being a breathtaking blast of glorious sound radiating out of full ensemble and filling the whole of the house. Dohm, who can be seen dodging the light of the fire, as well as PhantomCorps ensemble members who pop up and down and in and out of the orchestra pit opening directly onto the stage, captures the vocal brilliance and extraordinary harmonies of this incredibly talented cast, giving them a sound that is a step far above generalized community theatre talent.

You can try your best to upstage Berthe (Liz Weber) during the audience sing-a-long section of the show, “No Time At All” but you just won’t be able to. Weber, who has just the one number and scene as Pippin’s granny Berthe, is a proper hoot on stage. While the character is scripted to take some liberties in her interactions with both the musical director and the audience, Weber is loading the audience up with laughs when she commandeers the song away from Matthew Dohm’s control and reminds the audience that they can sing, but only on the chorus. She nails the hilariously fiery octogenarian character with flare and gives the other actors on the stage a good run for their money.

Holding his own against the chaos that is the dancing ensemble (doubling as soldiers) and the confusion that is Pippin (the character), Brian Lyons-Burke does a sensational job of bearing the crown of King Charlemagne. Spry on his feet, particularly during the sword fighting, Lyons-Burke dominates the stage as the tyrannical King whenever the moment calls for it. His body language well reflects the self-importance of the character. He delivers a robust sound during his well-articulated pattered verses of “War Is A Science” (a song which poor Pippin continues to derail with his naïve antics) and really exudes gusto when drawing this number to its confident conclusion. (This number is another excellent example of Laurie Newton’s choreography; the ‘soldiers’ are doing a clap-slap-shoulder-shuffle-slide-lean routine that matches Charlemagne’s patter.)

It’s impossible to take your eyes off of the sassy, scintillating Fastrada (Roxy Scintilla) the way she swishes, sashays, and saunters through every moment on stage. With villainous poise, Scintilla sizzles her way through the role and gives the audience plenty to love about what they see in her. It’s hard to hate such a saucy villainess, particularly when Scintilla slays in those glittery, sparkly high-heels. And when Scintilla takes to singing, her solo— “Spread a Little Sunshine” is a sensational smash. Bold of voice, fierce of body language and stage presence, and overall a superstar knockout, Roxy Scintilla was made for the role of Fastrada.

When it comes to Theo (Andy King) the role is rather easy to dismiss. In ‘traditional’ Pippin, Theo is just the lad who’s there to push Pippin along through the end. In Bannister’s Pippin, Theo is an integral component of the story right from the beginning of the show through to the harrowing conclusion. It can’t be spoken of, the ultimate moment of the show (because it’s such a shocking twist I wouldn’t want to spoil it) but King’s performance in that moment, along with all the other times they’re on stage, is stunning. King, who doesn’t get a solo of their own, becomes a golden thread weaving the story of Pippin between two realities— the reality of, well, reality (because it’s a bedtime story for Theo) and the reality of Pippin’s journey, which is in itself the reality of the bedtime story. King shimmers when they chew scenery in the background, particularly when it comes to the first act, doing things like holding up the map, marching off to battle, fully engaging with the story like the hyperactive imagination of a young child would. And when it comes to becoming the story in Act II, King doesn’t miss a beat.

Leading Player (Montria Walker) is a narrative figure in most productions of Pippin and while that is still sort of true for this production, Walker turns into more of a demonic ringmaster/psychotic play director, in keeping with Bannister’s framework concept. What’s special about Walker is the way she can kill a moment (bring it to a screeching halt) with just a ferocious glance. In this reimagined role of Leading Player, Walker is ruthless, particularly when it comes to interacting with Catherine, reminding Catherine of her place, of how she’s just on the edges of being ‘too old’ for the role. The dynamic shared between these two performers is brutal and it vilifies Walker’s Lead Player in a glorious way. You love to hate her. But you’ll love to love her powerful, soulful voice that slinks through sultry numbers like “Magic to Do” but blasts through “Glory” and “Morning Glow.” There is a palpable versatility in Walker’s Leading Player, not allowing the character to ever be the flat, one-dimensional ‘leading player’ that so many production of Pippin frequently present.

Catherine (Mallorie Stem) is a law unto herself. Without a complete understanding of the conceptualized framework and layering that Bannister has put onto this production, it would be very easy to state that Stem’s Catherine appears to be suffering some perpetual mental breakdown that grows exponentially as the production carries through to the conclusion. Stem has vivaciously animated facial expressions, which often read like she’s just teetering at the edge of her sanity, and she has a brilliant voice to carry songs like “And There He Was”, “Kind of Woman”, and “Love Song”. Though none of these songs are sang in the traditional sense, and it’s a completely indescribable magic (so you’ll just have to see it) when she moves through these numbers in the way that she does. “I Guess I’ll Miss The Man” (the song that Catherine doesn’t have but does…as written in Schwartz’ original— it’s the first real fissure in Pippin the play and the play-within-the-play in traditional productions) is a harrowing explosion of guttural emotions that mostly shriek-sung for dramatic effect. It’s definitely a choice moment and it resonates something fierce with the audience, even if it’s not wholly apparent to everyone as to why her character is making that choice.

And Pippin, oh Pippin (James Downing), he’s certainly got magic to do. Just for you. And everyone else in the audience. Watching Downing take the ‘Pippin-Journey’ in this particular production is a treat because there is are huge quantities of emotional depth to be plumbed here and Downing does so with vigor. There’s also a fantastic voice to back up all the singing the Pippin has to do. Downing soars his way through “Corner of the Sky” and floats more gently through “With You”, showcasing his vocal versatility. There’s a justified anger palpable and present when he bursts with internal fire into “Extraordinary” and even the moments where he’s merely observing life as it happens around him— like “Marking Time”— there is something truly wondrous about Downing’s performance. Filled with the volatile emotions of naiveté and desire, Downing’s Pippin brings the protagonist to life like no other.

It is ultimately an evening of entertainment. Pippin with The Fredericktowne Players has tremendous talent for everyone to enjoy, even if the concept doesn’t land or only lands partially or causes slight confusion. It’s a solid choice framing the production, giving it new and unique life, and the talent is simply extraordinary. You won’t want to miss it.

Running Time: Approximately 2 hours and 25 minutes with one intermission

Pippin, a Fredericktowne Players production, plays through Sunday September 12, 2021 at The Weinberg Center for the Arts— 20 W. Patrick Street in downtown historic Frederick, MD. For tickets please call the box office at 240-831-6138 or purchase them in advance online.