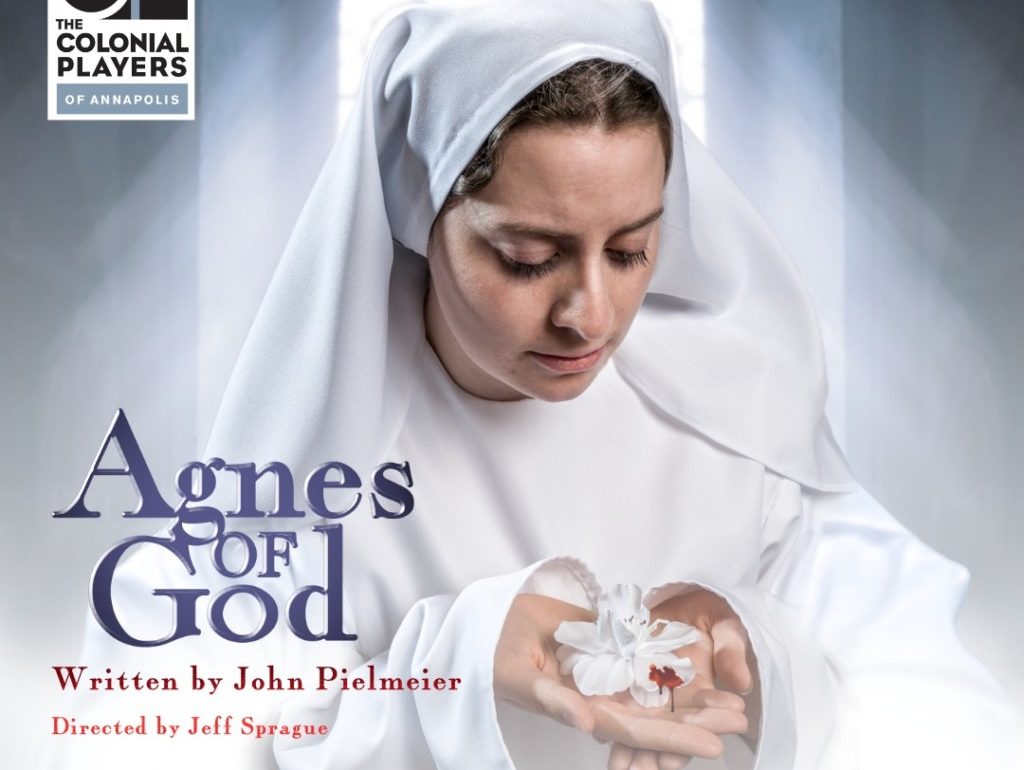

In his hyper-modern world what we have is logic and what we seem to have lost is faith. We lack a primitive sense of wonder and demand explanations for everything; miracles are dead. It’s no small miracle, however, that community theatres pulled through nearly two years of dark stages, surviving this pandemic where theatre artists were shuttered out of their existence. And bringing modern relevance to what could easily be considered a ‘dated’ piece is a theatrical miracle all its own. Colonial Players of Annapolis is presenting that miracle with their current production of Agnes of God directed by Jeff Sprague. Evocative, harrowing, disquieting, and completely discomforting, this controversial play, written by John Leonard Pielmeier, examines in excruciating detail the dichotomy between religious faith and atheistic believe in science.

Theatre in the rectangle is always an experience at Colonial Players and Agnes of God is no exception. The scene is set, designed by Terry Averill, to be deceptively simplistic. It’s a psychiatrist’s office, though truly the play takes place inside the principal protagonist’s memory, and Averill makes that clear with the basic desk, two chairs, and third chair for reclining and hypnotic purposes. But like the unreliable narrator in literature, the memory of a protagonist is colored by more than just the series of events and Averill reflects that divinely in his scenic design. The floor is painted to reflect the marble flagstones of a chapel; there are ropes that ascend to the ceiling, cross-guarded with an abstract ‘crown of thorns’, which are dotted with blood, and of course there are crucifixes and a statue of the blessed Virgin Mother Mary. All of these little nods to Catholicism and the way they encircle the play space are a direct translation of how that Catholic influence hovers around Dr. Livingstone’s memory in her temporal periphery, seeping into her assessment of her patient, which just so happens to be a novitiate of the convent.

The singular most impressive design element of the production is the work of Lighting Designer Eric Hufford, who provides us with a series of strictly delineated lighting cues, each one specifically assigned to a particular type of moment. The cooler overall lighting which appears when Dr. Livingstone is expressing her soliloquys and asides to the audience is very different from the forced-warmth of the yellowing light which appears in the direct conflict scenes with Mother Miriam and Dr. Livingstone. There’s a cold blue light, reflecting those questionable moments of pre-dawn whenever Mother Miriam recalls an encounter (which is then re-enacted for audience benefit) with Sister Agnes, and of course Sister Agnes herself, when singing, appears lit in this unholy bright light that tinges a weird shade of white-green. Hufford’s work has an almost cinematic quality to it. Accompanying Hufford’s cold blue moments, which only ever feature Mother Miriam and Agnes, Sound Designer Robin Schwartz floods the background soundscape with twittering birds and lone church bells, signaling some sort of distant memory trigger, fully enhancing those scenic recalls.

Agnes of God readily runs the risk of being drawn-out and poorly paced and the script it littered with potential booby-traps of dull. Director Jeff Sprague deftly avoids all of these problems and delivers a stellar if not stunning production of John Leonard Pielmeier’s work. Sprague should be commended for his succinct pacing of the performance. Not only do the scenes move swiftly and with emotional precision, there are a great many moments— particularly between Dr. Livingstone and Mother Miriam Ruth— when the realistic concept of ‘argument overlap’ occurs. All too often in theatre, a hot, heated debate, or roaring argument is happening on stage and lines are being delivered— person to person. Sprague has chosen the much more realistic approach and executed it flawlessly; when actors are shouting, they’re tailing in on each other’s lines, shouting over one another and carrying on as if they were really arguing. This seems like such a trivial thing, however, if you think about how you have an argument in a real life situation, you don’t let the other person get their full sentence out before you spit yours out and they do the same. Sprague has meticulously captured this authentic essence of high-strung emotional turmoil going back and forth in these scenes, and he’s done so without compromising the dialogue of what’s actually being said. It’s truly remarkable.

In addition to having this brilliant feel of argumentative reality to the scenes where these debates occur, Sprague has chosen three extraordinary performers for the diverse roles of these women in the play. Mary MacLeod as Mother Miriam Ruth, Laura Gayvert as Dr. Martha Livingstone, and Ashleigh Bayer as Sister Agnes are nothing short of the holy trinity when it comes to performing as separate entities and as one well-oiled theatrical unit. Although there are very few scenes where all three performers are featured together on stage, interacting in the same moment in time, when they do it is hauntingly mesmerizing.

When Mary MacLeod first takes the stage as Mother Miriam Ruth it is easy to write her off as ‘playing a Mother Superior’ because at first that’s exactly what it feels like. As the play progresses, however, all of these brilliant and subtle nuances crack the surface of her character, bringing depth and dimension to this Reverend Mother figure. MacLeod reserves most of the emotional gravitas of her character’s expression for the second act, though that isn’t to say she’s not present and at times even wryly humorous in the first act. A lot of the Mother Miriam Ruth character is the reactions she has— the way she absorbs the emotions and actions of those around her, be it in those moments of confession with Sister Agnes or those moments of sparkish debate with Dr. Livingstone. There is both a reverence and a tamed fire that dual for dominance in MacLeod’s performance as Mother Miriam Ruth, making her exceptional to watch.

As Dr. Livingstone, Laura Gayvert presents an enigmatic performance that keeps you on the edge of your seat in rapt attention. Reading initially more like a lawyer than a court-appointed psychiatrist, the way Gayvert slides in and out of her memory-recollections and the actual scene work is seamless. The recollections are delivered at the tops and tails of various scenes, not unlike Shakespearean soliloquys addressed semi-indirectly at the audience and Gayvert has a deft handle on how to exercise this technique. She’s never quite speaking directly at you but also you know she’s speaking to you; it’s fascinating and vexing all at the same time. There are more caring tones, bordering on maternal, when it comes time for Gayvert’s character to gain Sister Agnes’ trust and these moments bristle in sharp juxtaposition with the spitfire cut-downs that she delivers to Mother Miriam Ruth. Gayvert is edgy and provocative without pushing the envelope too far in her portrayal and she really holds the audiences’ attention full stop.

Appearing as the titular character, Ashleigh Bayer is what one might call a modern miracle in the field of acting. Her blind naïveté and impossible innocence are dazzling. Bayer brings a childlike innocence and juvenile virility of the simplest and puerile nature to the forefront of her portrayal of Agnes. These are the guiding tenants of her existence on stage, but that does not mean she is static by any stretch of the imagination. Bayer delivers petulant fits when Agnes is upset but does so in this very pitiable fashion which makes you feel for her. She presents a delicate and frail character who reflects fear and confusion in her eyes so much that you begin to feel afraid. The way Bayer can be frightened and simultaneously surging with ecstasy is unsettling in the most glorious way. She lives up to the textual description of vacillating between totally bananas and slightly off-center. Whenever there is something the Agnes character needs to say— be it in those hypnotic sessions or confessions with Mother Miriam— there are raw and visceral emotional outpourings from Bayer; they are surreal and yet evocatively intense. The entire second act, which is best left undescribed for fear of spoilers, is one brutally emotional roller coaster, which Bayer’s Agnes bears the brunt of, but is extraordinarily delivered by all three performers.

Agnes Of God is discomforting and disquieting, a true theatrical riot that will upend your senses, challenge your beliefs, and make you think. Director Jeff Sprague and his cast and crew have done a tremendously successful job of revitalizing this play and making it well worth seeing. Don’t hesitate to get tickets; it’s a must-see this season.

Running Time: 2 hours with one intermission

Agnes of God plays through April 2, 2022 at The Colonial Players of Annapolis— 108 East Street in historic Annapolis, MD. For tickets call the box office at (410) 268-7373 or purchase them online.