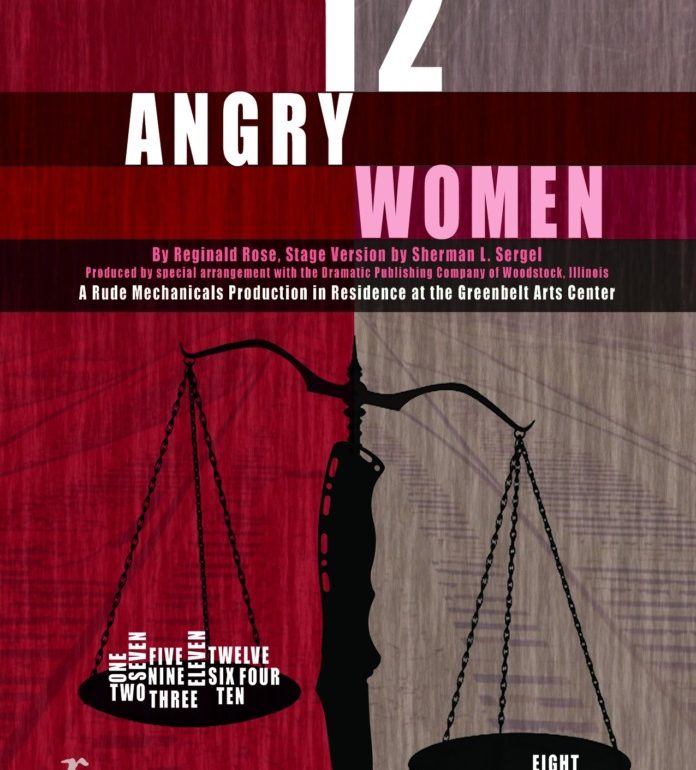

What is a reasonable doubt? Google + Merriam-Webster says, “A reasonable doubt exists when a factfinder cannot say with moral certainty that a person is guilty or a particular fact exists. It must be more than an imaginary doubt, and it is often defined judicially as such doubt as would cause a reasonable person to hesitate before acting in a matter of importance.” Perhaps we’re not asking the right question. Perhaps the question should be “what causes someone to have reasonable doubt?” If you want the answer to that, in a spellbinding and riveting 80 minutes of theatre, The Rude Mechanicals have the answer for you with their current production of 12 Angry Women directed by Ed Starr. Written by Reginald Rose with a stage adaptation of Sherman L. Sergel, this spitfire drama shows that tensions run hot when the balance of a life hangs in the hands of 12 strangers.

As The Rude Mechanicals find their way back to their theatrical feet, they’ve managed to smash this one out of the park in regards to perfectly paced, perfectly cast, and perfectly performed. It’s rare that such a brilliant trifecta of factors comes together in this way, but The Rudes and their talented cast of women (and the lone Peter Eichman who serves as the guard with two or three lines and an array of door-opening commitments) deliver a stellar production of a show that should be living rent-free in everyone’s minds all the time because of its perpetually relevant subject matter: What causes us— as flawed human beings— to explore and experience reasonable doubt when sitting on a jury?

Director Ed Starr, along with— (seriously, who does these programs??) “person-who-showed-up-to-build-the-set” Erin Nealer, and Lighting & Properties Designer Jeff Poretsky, craft a functional and era-appropriate set. While it’s not specified when the dated-ness of the production is meant to be, it’s clear given the subtleness in the scenery that this isn’t necessarily modern times. The room is bland but not sterile, unwelcoming but not completely isolating. It’s a curious blend of unpleasant things that one the whole aren’t bad but when put together with twelve women who would clearly rather be anywhere else, make for 80 minutes of intensely fascinating discomfort— for the characters. Costumes, compliments of the cast, really suit each juror to their personalities, and the whole aesthetic of the show is primed for intensity without appearing to be anything other than a locked room with one window and twelve individuals trapped inside.

Starr’s casting is sublime. Each of the jurors feels as if they were born for the role they’ve landed themselves in— another rarity in community (and sometimes even in professional theatre.) All too often it’s a stellar lead and a great supporting actor, but this cast of twelve women is outfitted to perfection. And the pacing is spot on. You’re glued to the discussions (even if there’s a slight hiccup of a line here or a fumble of a word there— it feels authentic— you and I hiccup and stumble over words, especially when tensions are rising.) There are no dull moments, even when it seems like nothing is happening; Starr has so firmly grasped that palpable tension and unease in the air that you feel just a little unsettled watching these jurors as the play devolves to its conclusion. And while you probably won’t remember to look— because the actors are so engaging— watch the clock. It moves in real time and changes when swaths of time are supposed to have passed.

The voice of outside reason comes through in Juror Eleven (Malia Murray.) Calmly but resolutely reminding everyone that their myopic focus on guilt blocks the more global perspective of how liberating it is to even have the option of trial by jury. Murray is quiet in her delivery but firm, like a sagely pillar of wisdom waiting to whisper into the crowd, but only once she knows for certain that her advice will truly be heard. Juror Five resonates with more of the silent but deadly type (at this performance played by Jaki Demarest.) With the trench-coat black leather and appearing to be something straight out of streetfighter, Demarest brings balance to the initially ornery character, arriving as callous and detached but shifting her position reasonably as the experience dictates. Surefire in her knife demonstration, it is easy to believe that Demarest’s juror came out of the slums in a ‘rough neighborhood.’ There’s also the moment early one where Demarest completely loses her cool when being called out about growing up in the slums. It’s like watching a steampipe explode, gnarly and insanely dangerous.

Juror Nine (Penny Martin) is at first stalwart in the opinion of guilt— as all but one of the women on the jury are, coming into the play— but manages to make a humanizing push for one of the witness testimonies when called into question. Martin uses empathetic compassion to express this point and it wholeheartedly received by the audience, if not by some of the other jurors. Juror Six (Rachel Duda) is one of the quietest of the bunch, staying almost statuesque and silent until called upon to forcibly present an opinion. Authenticity in Duda’s explanation is palpable and you get the vibe that she’s an older mom just there to fulfill her constitutional obligation of being on the jury. She doesn’t want to fight, argue, or even rock the boat, she just wants to do her duty and get out of there. Juror Twelve (Holly Trout) keeps a firm handle on their character’s bottled up emotions, allowing to trickle out in well-articulated moments without the more spastic outbursts attributed to some of the other jurors.

Juror Two (Renee Namakau Ombaba) shifts and slides, putting on a tempered outburst at the beginning, which she quickly follows up with a relentless foot fidget seen beneath the table. Ombaba makes the deliberate choice of a physical manifestation for her feelings as well as her anxiety. It’s more than just being frustrated with the situation, it’s a tell for the character’s anxiety as well. Juror Four (Ayanna Fowler) presents a polished and poised composure throughout the deliberation. Fowler and Ombaba have a scripted scene where they cross together to have a ‘silent discussion’ as the clock moves, the lights dim and rise (to indicate the passing of time) and it’s almost like a session of personality-dialysis in that unspoken moment, where Ombaba has infused just a hint of her anxiety into Fowler’s juror and Fowler has managed to successfully transfer some of the calm, collected compassion from her juror into Juror Two.

Juror One (Carey Bib) serves as the Foreman, or in the case of twelve differing opinions, the wrangler of cats. Bib, though not wholly impartial, does a fine job of maintaining order amongst the women, particularly when temperatures spike off the mercury and physical altercations almost start flying. Having a guiding stage presence, which sneakily commands attention without demanding it, Bib feels like the utterly perfect choice for Juror One.

Juror Seven (Sarah Pfanz) is one of the more stubborn and prickly Jurors, though perhaps not so bad as Juror Ten (Laurel Miller-Sims) or Juror Three (Melanie Jester.) There is a level of attitude that Pfanz brings to the table though she’s not wholly incapable of capitulation. Her ability to draw all eyes to her when she’s speaking is impressive and the way she drifts through the room when moving is particularly intriguing; there’s just something about her movement as this character that is uniquely engaging to the eye. Miller-Sims’ Juror goes on a racist/xenophobic tear late in the performance that has everyone’s teeth on edge, jurors all around the room turning their backs to her, and puts a palpable revulsion for her attitude into the air. (The play never specifies what race the accused young lad is, but there are references to urban living, an ‘othered’ nature, etc. that presumes the individual to be not-white.) There is a truly striking moment toward the end, which can’t be explained in great detail for fear of spoilers, but when Miller-Sims does the thing with their glasses, and the expression they make— it is beyond priceless.

Melanie Jester brings Juror Three to obnoxiously repugnant life in a way that defies good description. But before we get into how truly talented Jester must be to bring this repulsive character so bombastically to life, she has got to be praised 100% for her spot-on black and white polka-dot ensemble. Pants, top, the damn accessory fan, purse, shoes— the whole nine yards in stellar black and white polka dots. (Because this character literally sees black. And white. In all contexts appropriate for this infuriating antagonist.) It takes a special level of talent to have a character walk into a room, hardly even speak, and already have the audience hating that character within a matter of minutes and Jester possess that talent. Juror Three is nothing short of a monster; you would struggle to say she’s just a product of her raising or her experience, so thoroughly has Jester brought her vileness to the surface. And it makes for a knock-down, drag-out, showdown for the entirety of the show.

Devora Zack starts as the lone possessor of ‘reasonable doubt.’ At first, especially if you don’t know the play, when you see Zack’s Juror Number Eight, staring haplessly and gormlessly out the window, you quickly write that juror off as the “do-nothing” juror. And yet it’s Zack’s Juror who gets the whole commotion exploding. With an exhaustive amount of dialogue, Zack calmly and steadfastly explains her reasoning, her logic, her feeling. And she can hold her own against the tyrants of the room, like Miller-Sims’ Number Ten and Jester’s Number Three. Pushing the other woman to reexamine evidence, to reconsider facts to reenact testimony (we’ll forgive her and the rest of the cast for not knowing how to mark out distances…there performances are that good), Zack is the lighthouse of curiosity in this production, not necessarily guiding or leading, but blinking in the darkness of ignorance, preconceived notions, and stubborn roots of experiences.

Ultimately one of the finest productions ever achieved by The Rudes in recent history, 12 Angry Women is a powerhouse play that will give you 80 minutes of riveting dialogue that readily becomes action on the stage for all to consume and consider.

Running Time: 80 minutes with no intermission

12 Angry Women plays through September 10, 2022 with The Rude Mechanicals, now in residence at Greenbelt Arts Center— 123 Centerway in downtown Greenbelt, MD. For tickets call the box office at 301-441-8770 or purchase them online.