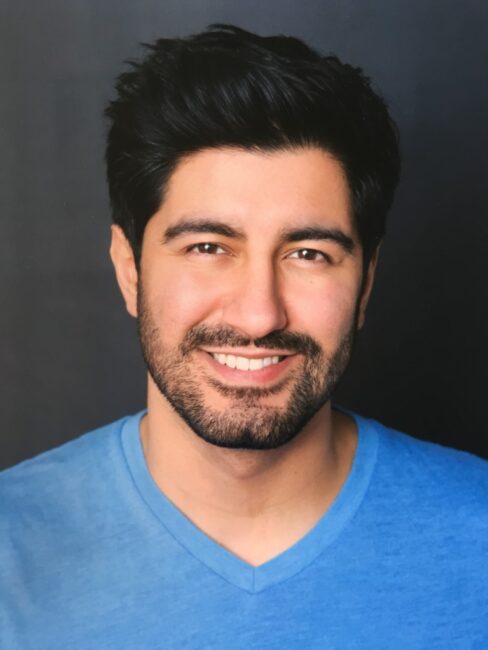

Media sensationalism, news-blips, and the never-ending stream of immediate access to everything, everywhere, and all at once has led to more than just empathy fatigue. In the minds of the masses, particularly those more technologically engaged with social media, it has led to cultural shortsightedness. A thing is happening. Somewhere that isn’t here. And it’s unfortunate. And we feel bad. And we move on. But that doesn’t mean this is the first time, the only time that such a thing has happened. Selling Kabul, a play by Sylvia Khoury, may hit home hard because of the recent 2021 evacuations in Afghanistan. But the play itself takes place in 2013. The issues contained with the story have been happening for decades, not just since President Biden ordered the evacuation two years ago. In a TheatreBloom phone-interview-exclusive, we speak with Yousof Sultani, playing the role of Jawid in Signature Theatre’s production of Selling Kabul about the overall experience, about being a first-generation American born to Afghan parents, and about what this show means to him as an Afghan.

Thank you so much for giving us some of your time to speak about what sounds like a very captivating piece of theatre.

Yousof Sultani: My pleasure! Any opportunity to talk about Afghanistan and the work that we’re able to do about it is an opportunity that I jump at.

That’s fantastic. Can you tell me a little bit about why you wanted to get involved with this production of Selling Kabul? What was the draw for you here?

Yousof: My parents are from Afghanistan. We so rarely get to see Afghan stories being told on stage. And if we do, they seldom involve Afghans themselves. They just recently did The Kite Runner on Broadway and I believe there was only one Afghan in the cast. I’ve actually had the honor of performing in this show— Selling Kabul— before. I just did it last year in Seattle. I played Taroon in that rendition of it and Taroon is the young man who is the translator, working with the U.S. Military; he’s the one in hiding. With the Signature Theatre production, I get to play a different character named Jawid, who is Taroon’s sister’s husband, so the brother-in-law, who is also facilitating and assisting in trying to hide Taroon.

For me, I was actually born and raised in Virginia. Growing up I went to Signature Theatre and Woolly Mammoth and Arena Stage as a student and as an audience member who loved theatre. So any chance to be able to come back home for me has always been something I jump at. I’ve gotten to work in DC the past couple of years. I did A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini at Arena Stage. And I did this play called This Is Who I Am (by Amir Nizar Zuabi), which was about a Palestinian son and father who are dealing with grief, the son who lost his mother and the father who lost his wife. That happened over COVID so it was a Zoom play but it was done live every night. And that was at Woolly Mammoth. This is my third play in DC.

Being Afghan was another reason that I wanted to do it. I had a chance at two other shows that I had offers for both out in California that overlapped with this and it was a very easy choice to be able to come home and be with my family, but also to do so and tell an Afghan story in a region that has one of the largest diasporas of Afghan people in America.

You mentioned this was the second time you’ve been a part of Selling Kabul, playing a different character this time around. How is this time around different, other than the obvious notion that you are playing a different role, for you? What is the experience of getting to do it at Signature, knowing that it’s a theatre in your own backyard where you grew up. What has that been like?

Yousof: It’s wonderful. It allows me to see the play in a different aspect. Playing another character who is also Afghan but who lives a very different life. In this play, Taroon represents a large majority of Afghans who are actively against the Taliban. And most everyone in this play feels this way because of the oppression that the Taliban brings to people, specifically dealing with women and children. Taroon represents a younger generation who’s worked with the U.S. Military to better themselves, to better their environments, to better the people, and to work with Westerners for better ideas. Originally it was to implement a democratic government and work towards a better country and a better future for its people.

In this play, Jawid (the character Yousof Sultani is playing at Signature Theatre) is someone who is a survivor and a provider and a protector. He doesn’t have the capabilities that Taroon does. He doesn’t speak English. He’s just the type of character who represents a large majority of Afghans in the sense of “family first” and “protection and providing first.” So Jawid is, unfortunately, put into a position where he has to work with the Taliban. And in having that position it actually allows him to protect Taroon. It’s this crazy duality; these two people on the opposite ends of the spectrum as far as— not where their hearts and intentions lie— but where their actions lie. They are very similar in how they feel for Afghanistan and their love for it, their passion for it. But for me, it has just been an amazing experience to just play the opposite of what Taroon represents.

There is turmoil between these two characters. It’s mostly one-sided; Taroon feeling like Jawid is working with the Taliban, that he’s working with people who have actually destroyed Afghanistan for the past two decades with their religious oppression and their treatment of people and their hunger for power and greed. A large majority of Taliban aren’t even Afghan; they’re comprised of members of other countries. So playing this role, for me, has allowed me to have a different aspect of the Afghan experience, which I am incredibly grateful for.

That sounds striking. What would you say have been some of the challenges you’ve encountered taking on this role of Jawid for this production?

Yousof: It’s interesting. As a company, on our first day of rehearsal, our brilliant director, Shadi Ghaheri, and our cultural consultant, Humaira Ghilzai— who is Afghan and usually a part of any kind of Afghan production or film in this country— they both decided, Shadi and Humaira, because it’s in DC they wanted to start the play with a clip of Joe Biden talking about the evacuation, which would have effectively changed the timeline of when the play takes place. We had this wonderful, open-hearted discussion about how we felt about that. The relevancy of it was very important. I, along with another Afghan in the room, actually advocated for keeping the setting and the timeline of the play as is— which is 2013.

During this time, Obama is starting to evacuate a large number of troops. American occupation is still very present there but a large majority of U.S. Soldiers are being recalled back to the states. And they’re leaving Afghanistan. So there’s this shift in the paradigm and the power structure happening there. And the Taliban are slowly but surely gaining more ground, and as we saw, inevitably, they overtook the country again. The thing about that is that in 2013 there was a different mindset about helping the Taliban for a sense of survival as opposed to helping the Taliban as Jawid in 2021. I think audiences would be less empathetic and possibly a bit more judgmental about Jawid in 2021 than they would have been in 2013 because of the costs and what has happened to the country since the Taliban has come back into power.

And also for us, as Afghans, I think it was very important to just remind audiences that this has been happening for decades. It’s not just a recent thing where Afghans have been trying to gain SIV (Special Immigrant Visas). It’s been ten years since this play has taken place. And there Afghans— translators, interpreters, people who have helped the U.S. Military with digging wells, finding water, navigating different towns and maps, learning the topography— those Afghans who did all that, assisting the U.S. Military have been put on kill-lists by the Taliban. So if audiences come in asking, “what’s the significance of setting this in 2013, it doesn’t make sense, all this stuff has happened recently”, I think that’s when we realize that it’s lost on people— we have selective memory loss about how long these events have really been taking place. We’re hoping that the audience members are going to come in and see that this was happening in 2013 and that we’re still dealing with it. From my perspective, it hits you in a different perspective rather than thinking that this has all just happened in the last two years.

I agree. I think all too often when people look at something only through a modern/actively-happening lens of ‘present day events’, it can become ‘relevant sensationalism’ and the sentiment can then too easily become, “Well this is just a ‘right now’ problem.” And because of the way we ingest information— at the touch of a button, in our pockets, everything, everywhere, and all at once— it’s much more readily disposed of.

Yousof: I agree!

To me, that’s frightening in a sense because it just becomes another thing that’s happening someplace else. And it’s so much easier to forget about. I think if you can put a more dated time stamp on a thing— that it’s not just occurring right here and now, that it has been happening for a decade or more, I think that does broaden the perspective of how people view it, hopefully realizing that we’re still dealing with that issue, and hopefully asking why we haven’t come up with a better way to address that issue.

Yousof: That’s incredibly valid and I completely agree with that. There’s also this thing called “empathy fatigue” that comes into play. There’s just so much happening all over the world at one time and as humans, we’re just constantly thinking about, sending thoughts and prayers, and being active about helping certain causes. But the fact is that even with all of that, these causes are still happening. After the evacuation of Afghanistan? We moved on to the war in Ukraine. And now we’re on earthquakes in Turkey and Syria. These are all things that absolutely require attention but they usually come at the cost of something that we hadn’t completely fixed or been able to finish addressing. So when you look at it and think that what’s happening in Afghanistan is something that’s only been happening for the past two years, that’s just not true. It’s been happening for two decades.

That’s an incredibly powerful statement that I hope people can wrap their minds around. I think one of the beautiful and unique factors that you have with a play is that it has the potential to have a lasting impact, if for no other reason because it forces the audience to engage with it for a set length of time. It’s not a news-blip or a 15-second streaming video on social media. How long is this play?

Yousof: Generally, the production runs about an hour and 30. But I think our director has chosen to tinker with a few more moments and our run-time right now is around an hour and 40 or 45. It’s a one-act play and it’s definitely longer than a news-blip. But that’s the beauty of theatre. There was a study— I don’t know if you’re familiar with it—I think they did it at UCL a few years ago. They did this study where they used a multitude of different theatrical performances and they continually hooked up audience members to heart monitors so they could track their BPMs. Theatre is the only artform where the entire audiences’ heartbeats synchronize while watching a performance. I think that’s so incredibly beautiful. It’s an immersive artform.

What’s the most important part of Selling Kabul for you?

Yousof: The most important part of this play is that it humanizes these characters that to us, as Westerners, are ordinarily just numbers that we hear about on a ticker of things that’s happening. Like you said— they’re over there, we’re over here living our lives, what can I do? And we get a statistic— 10,000 people died. And this play is a way to understand that better. It gives us a way to understand what these people are going through, the immense amount of stress that they’re under, the depression that they deal with, and how they continue to move forward. But there’s also moments in this play that are about light and hope and are funny. That’s the thing— it’s the human experience. For audiences who are coming to see this show who are just expecting to see this really drab and depressing story about what’s happening in Afghanistan, you’re also going to see a very universal story about a husband and a wife facing hardships. About loss, about gain, about future and the hope of a future and that’s the brilliance of theatre. And for this play in general, although it’s set in Afghanistan, it’s a very human story.

I read in your bio that you are dedicating this performance to your late father and I’m very sorry to learn of his passing; you’d also mentioned that you were staying at your mother’s at the moment, is she going to be able to come and see you in this production of Selling Kabul?

Yousof: Thank you. Yes, absolutely she is. She didn’t get a chance to see it in Seattle so she’s going to come along with my brother and my sister, who also live in Virginia. And we’re hoping that a large amount of Afghans will be able to come out and see this show. It’s definitely a play that I hope to direct myself someday just because I’ve had so many great experiences with both directors both times with this show and now I have some of my own ideas. It’s such a wonderful story. I live in Chicago and it hasn’t been done there yet and I think it’s a very relevant piece. When you’re sitting there listening to two brilliant women direct and have all these crazy ideas and then you have something that riffs off of that, it’s great. And also, connecting to the piece on the level that I do being an Afghan— the play isn’t written by an Afghan and it’s not being directed by an Afghan but thankfully its starring an Afghan— Awesta Zarif who is playing Afiya and then myself. Shadi (director Shadi Ghaheri) pushed very hard to try to get as many Afghans in this piece as she could. I’m forever grateful for her for that, for her casting the two of us.

I know I asked this before, but what does this piece mean to you personally?

Yousof: Having had the chance to have done it before, when they did this piece off-Broadway, it was right around the time the 2021 evacuation was happening. I actually stopped acting for a few months and I had a few people reach to me as an artist because they needed someone here to be able to write recommendation letters for citizens in Afghanistan, people of Afghanistan who were artists, journalists, directors, photographers, to work with people in America in hopes that they could apply for a visa because there was such a mass hysteria to evacuate.

We were doing everything we possibly could to get people out of the country. I ended up becoming involved in a effort to get a multitude of people— like 250 people that we had on file— out. I was working with 15 people under me and taking calls at four, five, six o’clock in the morning. A few of them were my family members, so I was translating and setting up spots. I was very much involved and hearing stories every day and the amount of stress that my family and these people were under— having traveled between Kabul and Mazar-e Sharif when the airports were shut down, and then being told to go back for pickup— so having lived through that, having an understanding of that and having that daily reminder that I’m actually talking to people whose lives are in danger on a daily basis, and I’m safe here in America doing whatever I possibly can… that wakes you up. We had a couple of military contacts that we were consistently speaking to and checking in with. We had a big email chain, we had google-docs with everyone’s passports and identification information. We had lists of if they had family here and all of their family’s social security numbers and contact information. And we tried so very hard to get them brought into the country and placed safely but so many of them are still there.

As an Afghan it’s so difficult to see— my family is still there. So this story— Selling Kabul— hits me in a multitude of ways, which is why I connect to it so much more than just being an Afghan. I cannot speak to it the way people who have actually lived through it have. But just on a daily basis, getting these phone calls and hearing their voices— knowing these are real people— it was a very emotional time for me.

I cannot imagine what that must have been like for you and I am so sorry that your family is still there. Has having this experience given you new ways to access telling the story as these characters in Selling Kabul?

Yousof: I definitely did in the Seattle production as Taroon. Having heard these stories of loved ones actively trying to flee, discussing their options of how we get them to Germany or across the border to Iran, there were certain aircrafts that were making those flights and how much money did we need to find to be donated, and reaching out to all the different societies looking to have them donate to that funding, it was very much something that I understood. And it helped me to understand what Taroon was feeling— that moment of being trapped and feeling scared and needing to get out. But also, Taroon stays because he has a wife and a child, who is newly born and his wife is in the hospital. That is such an important plot-device in this story because otherwise, Taroon would have probably left or gotten to leave. But he chooses to stay as along as possible until his wife and child are safe.

That is a sentiment that was shared by so many Afghans. The amount of people that were reaching out to me here, that heard I was doing the work I was doing, sending me more people and more files— telling me that this family was in trouble because of this or that family was in trouble because of that— it was incredibly overwhelming. For me, I was no longer seeing numbers, I was seeing faces, I was getting names, seeing photographs and videos. They weren’t just a statistic anymore. Then I’d get on the phone, speak to them, and it became even more real. With Taroon, I really felt all of that and it fueled my performance in a different way because it wasn’t just about an actor being on stage telling a story, it was about an activist hoping to be able to shed some light on this matter while it was still very much— not in its infancy, but early on. This was early in 2022 when I originally did the production in Seattle and the evacuation happened in 2021. It was just so real for me.

This time around, as Jawid, there are Afghans who— I don’t want to say ‘have chosen their fate’— but there are Afghans who simply are not capable of leaving. They don’t have the means to leave, who didn’t work with Taliban or U.S. Military and are just surviving and don’t have anywhere to go. And then there are some who do choose to stay because it is Afghanistan but then there are others who actively don’t have the means to go. It’s a very different aspect with Jawid and I have to approach him from a very different sense and I think that I have.

What would you say has been your biggest personal takeaway, I know you were just talking about how you had to approach the character of Jawid in a very different way from when you played Taroon, but what has this experience with this character taught you about yourself as a person, as an Afghan, as a performer?

Yousof: That’s a very good question. Everything in a theatrical piece is a journey from the first rehearsal to the final curtain at the last performance. I don’t know if I’ve completely allowed myself to feel all of it just yet. We haven’t even performed in front of an audience yet and sometimes I don’t what I’ve fully taken away from the experience until the end. But what I can tell you so far is this. In having had the conversation that we had as a company about changing the play’s setting from 2013 (where the playwright initially set it, and Signature Theatre’s production is currently setting it) to 2021 (a discarded directorial concept), that would have changed my opinion.

As an actor, you try to never judge your character, that’s the goal: don’t judge your character, put yourself in their position, make the choices they make based on their situation. If we had changed that setting, I think for me, I would have naturally had a different opinion of Jawid. I would like to think that I would still have had an enormous sympathy and understanding for his character. When I first read this play, and maybe it’s just the American in me, I have always leaned and felt very close to Taroon as Afghan. With his understanding of the Taliban, what they’ve done to his country, and the amount of oppression they’ve forced onto the people of Afghanistan.

But now it’s this sense of something that I’ve never had to do: surviving in the most basic sense. And allowing nothing to get in the way of the safety of my family and of their future and protecting them at any cost. It is something that as a human being I am thankful for that I’ve never experienced that kind of hardship the way Jawid has. He’s to the point where he’s willing to do things that will bring him shame and immense trauma in the name of securing a future for his family. And by that I just mean being alive. As an actor, I hope no one in my position ever has to experience anything like this and doesn’t have this personal experience to pull from in this regard to bring this on stage with them. But thinking about this character, that’s something I can take away from this experience: this is a human experience that I haven’t had to endure.

Artists are supposed to be empathetic, that’s what we do. We deal in empathy. And every role that I ever get a chance to portray, there’s an understanding there— hopefully— that I haven’t had before. It’s a perspective that I haven’t had before that I get to learn about myself as I’m learning about the character. I think gratitude is a big one that I’m going to be taking away from this. It is absolutely possible that I could have been in Afghanistan at this time, if my parents hadn’t left during the Russian invasion. I still have family there. I’m first-generation American. My parents were immigrants. This very much could be my life experience. Jawid is in his late 30’s. I’m in my late 30’s. My parents were born and raised in Kabul; this story is set in Kabul. This is happening during the Taliban regime. This oppression is real, my sister would have had to wear a hijab and wouldn’t be educated. She’s a brilliant, phenomenal lawyer here and she would not have had that experience and education in Afghanistan so there is just this sense of gratitude that I feel— for my parents, for the country I live in now. Though there’s also a bit of resentment towards American in this process, of course.

There’s a sense of duality there as an Afghan-American. But there is also this sense of pride. They call Afghanistan the Graveyard of Empires because it’s never been conquered all throughout Afghanistan’s rich history. From the invasions of Genghis Kahn, from Alexander the Great, the Anglo-Afghan wars where the English were trying to colonize Afghanistan, to the Russians where they were beaten back by basically rock and stones. That’s always stuck with me; the strength of these people and what they’ve endured for centuries and I think a lot of that lives in Jawid.

This production sounds absolutely incredible. If you had to sum up your experience, this time around, playing Jawid in Selling Kabul at Signature Theatre, in just one word, what one word would you use?

Yousof: I think I’m going to continue with gratitude. Or grateful. I’m grateful that Signature Theatre is doing this piece. I’m grateful it’s being done in Washington D.C. where there is an opportunity for members of congress to be able to come see this play. There’s an opportunity for people in power to be able to come see this play. There’s an opportunity for Afghans, there’s a large population of them in the DMV-area, for them to be able to see themselves on stage and not just their stories being told. They get to see Afghans portraying Afghans on stage. I’m grateful for this story being told in my backyard where my family and friends can come see it.

Selling Kabul plays through April 2, 2023 in the Ark Theatre at Signature Theatre— 4200 Campbell Avenue in Arlington, VA. For tickets call the box office at (703) 820-9771 or purchase them online.