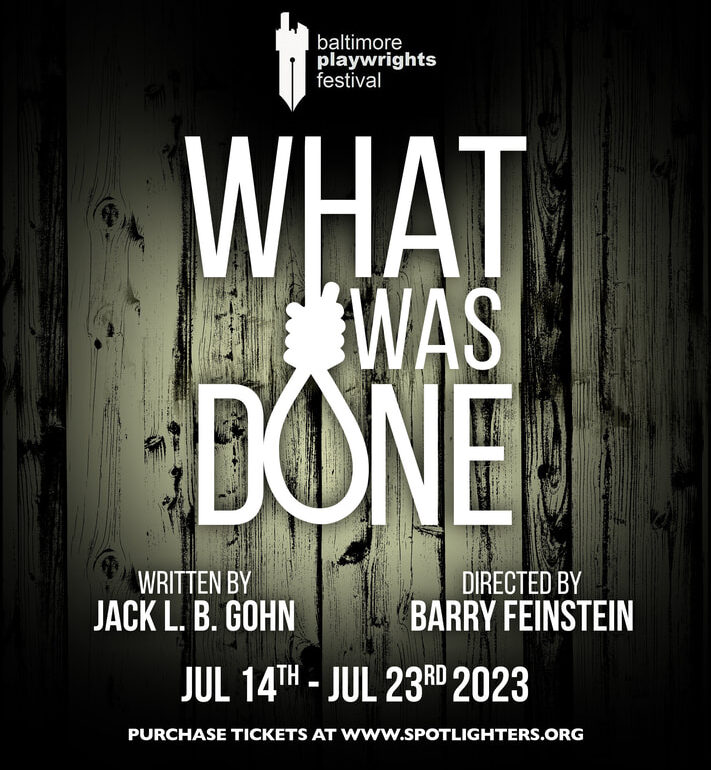

It’s never an easy task to tackle a difficult subject, particularly when attempting to speak about a narrative that isn’t necessarily your own. What Was Done, a world-premiere play by Jack L. B. Bohn currently being produced for the Baltimore Playwrights Festival by Miriam Bazensky and Directed by Barry Feinstein as a co-production with Spotlighters Theatre, is a play that leaves the audience with more questions and awkward comments than anything else. The premise is that a white woman in 1978 makes a family discovery tying her to her current dissertation research, the last lynching in the state of Maryland, which creates an uproar in her immediate family life of being married to a black man and having a bi-racial child. The play itself is riddled with plot holes, ripe with problematic white-washing, and loaded with a whole bunch of anachronisms that make it intolerable, bordering on untenable as a work of theatre. The concept is good, shedding light on a dark topic and dark occurrence in Maryland’s history; the execution is flawed, poor, and generally unpalatable because of the playwright’s overall approach, lack of finesse— in both word choice and overall subject presentation, and general lack of understanding when it comes to how to write for the time-period, how to write dialogue, and with locality for frame of reference when it comes to writing about Maryland.

The play itself could have been drastically better served had it been set in 2003 or 2013 rather than in 1978. There is nothing in Jack L. B. Bohn’s writing to indicate any sort of understanding of the time period of 1978, which is horrifically surprising given that the playwright lived through that time period. After seeing the play, with the modernity inflected into all of the dialogue, one might expect the playwright to be of a younger generation, perhaps born decades after the 70’s, but this is not the case. The concept of having a direct, living descendant to the “last lynching in Maryland” is still feasible and even believable had the play been in set in 2003 or even as far forward as 2013. And the concepts being discussed, with southern family members not believing in mixed-race families, being blatantly racist and disproving of non-white people having equal rights, and the general issue of fighting for civil rights are all just as relevant now (if not more so) than they were in the 1960’s and 1970’s, which is a recurring theme that the play keeps repeating. The antagonized characters of Alex and Kibuka, and somewhat Dierdre, but that character is problematic in her own right, would have much firmer ground to stand on in speaking about what they hope could come of the injustice; reparations and restitution hold far heavier weight for the implications of this show had it been set in a more recent time frame like ’03 or ’13.

Nothing on the set, except maybe the physical telephone, gives any indication that we’re in 1978, nothing in the costuming (don’t even get me started on the modern shoes…we’ll let that slide as this is a community theatre production on a budget), and certainly nothing in the delivery of the characters’ speeches gives any hint that this play is taking place in 1978. Or 1977 or 1980, depending… because the characters multiple times over make differing references to the “last lynching in Maryland…1933…saying 44, 45, and 50 years ago” interchangeably. And while there is nobody in the show’s program credited with responsibility for the props of this show, the responsibility of checking to make sure what you’re putting on stage fits your play’s historic setting is still there. In this case, the blame falls to the shoulders of Director Barry Feinstein and Stage Manager Herb Otter… for putting Tito’s Vodka FOUNDED IN 1997 and 100 Years of Lynching PUBLISHED IN 1996 in prominent points during this production. If you’re performing on a grand proscenium where your audience is at least 25 feet back from the stage, maybe you can get away with that. When you’re performing in the round at Spotlighters theatre where the nearest audient is a half a foot from the stage, not so much. There isn’t really an acceptable excuse for having props that didn’t exist until the mid-late 90’s, which feature frequently as plot devices in a show set in the 70’s, being clearly visible in an intimate space such as Spotlighters. Particularly at Spotlighters, where the ‘in-the-square’ staging and overall intimacy of the performance space doesn’t allow you to hide anything, you need to be aware of these things.

The play itself, historical anachronisms aside, just doesn’t hold up as believable. Even given the creative licensing the playwright takes (the last lynching in Maryland did take place in 1933 but the names, what happened, and why are very different than the narrative Gohn portrays), the show just doesn’t work as its currently written. I think the kids would even say it has “the ick” as it white-washes what could have been a powerful narrative that really should have brought something beautiful to the attention of the masses.

The ending of the show is a disgusting display of ‘white guilt mentality’ where the white person, who is still supporting racism by staying happily married to the white supremacist woman and being friends with her white-supremacist brother, states that he doesn’t want to agree with them but asks his black family members (the man to whom his niece is not married but shares a child with) to forgive him, and share a toast with him to the memory of the lynched man on the spot where it happened. This puts the burden of “please make me feel better about my support of systemic racism by doing this thing with me” on those being systemically oppressed.

And that’s just the ending…which runs on way too long. It needs to have ended with the “Amen” decry from the Alex character, rather than having this forced moment of reconciliation where the Selby character (the low-key not-really-racist-but-still-staying-married-to-one) shakes hand with Alex and Kibuka, hugs his niece, everyone leaves the stage but him and he’s left standing there with his thoughts as the lights slowly fade away. And we’ll completely overlook the fact that we’re pouring the 14-year-old character shots of whiskey for the toast because the play is problematic enough without bringing that up as a salient point of believability. Yes, under-aged kids drink, but the fact that it’s used as a comic device of levity (the kid starts cough-choking because clearly he’s never had alcohol before) in what should be a deeply profound and somber moment of reverence is just ridiculous.

The relationships in the play feel trite, contrived at best, and completely unbelievable the more you look at them. You wouldn’t have the Deirdre character, who is written with a one-dimensional flatness and seems to do nothing but whine the entire show long (and this isn’t a slight or comment on Jessica Rota’s performance, you ingest the script you’re given and you follow the directions of the director), staunchly defending her semi-estranged mostly-racist uncle when she’s passionately in love with this black man and they have a 14-year-old son together. It might be more believable if Selby was her estranged father that she was desperately trying to reconnect with or change his mentality because she wanted her father in her and her son’s life. But there isn’t enough backstory to explain why this uncle is so important. It’s not made clear that maybe he was a father figure, or raised her when the mother couldn’t, or anything like that— so the relationship dynamic between Selby and Deirdre just doesn’t create the necessary traction for legitimacy of their interactions.

There’s also no believable universe wherein a mixed-races couple— white woman and black man— would be together (albeit living apart) for 14 years from 1964 to 1978, raising a child together, and the big reveal of “the last lynched man in Maryland was my biological father” would not have come up during any point in their relationship until the exact moment of “INSERT PLOT TWIST HERE” the way it does in this script. The script is clunky in general, and Director Barry Feinstein’s pacing doesn’t help matters. There isn’t enough done to delineate when they’re outside versus when they’re inside and when they’re down in Southern Maryland versus when they’re in the apartment/home in DC. In Feinstein’s haste to attempt to tighten the script’s poor dialogue, he has actors rushing onto stage for the next scene before the blip-blackout has even completed, occasionally with other actors still trying to make an exit. And this only adds to the confusion of who is where. (And yes, it sort of states where each scene takes place in the program, but you shouldn’t have to constantly be deferring down to your program, in the darkened theatre to see where the action is on stage.) At the Friday night opening performance there also appeared to be some lighting issues whenever the completely superfluous character of Mike Pumphrey was on stage making a phone call. Sometimes he had light, sometimes he was in darkness, and it wasn’t clear if that was just a malfunction or someone on the creative team trying to be clever. The actor playing Pumphrey, Richard Peck, was actually a solid performer despite only having a moment’s worth of dialogue and the character itself being unnecessary to advance the plot.

A great many of the Maryland-locale references felt forced into the play. It almost felt as if Gohn hadn’t ever lived in Maryland but instead, googled “what do the local people do” a la Camelot “What Do The Simple Folk Do?” and plugged in suggestions like crabs and Old Bay. There is nothing intentionally definitive that sets this play in Maryland other than the shoe-horned references, and honestly, despite being full of local pride myself, the play would have been better served if it was just “a town like yours not too far south of the Mason-Dixon line.” Gohn’s attempt to force specificity on the show didn’t help make his point any clearer. And if you’re going to force state references, maybe get them right? Selby gives Kibuka a hockey stick (it’s meant to be a generalized show of how the semi-racist estranged uncle keeps giving ‘white boy’ presents to his black nephew) and says “it’s the state sport.” Jousting has been the Maryland state sport since 1962. And maybe it seems harsh to pick apart all of these little details in Gohn’s work, but if the plot were stronger, the characters believable, the narrative not white-washed, then maybe the details could be more readily overlooked. Little things, like simple word choice— when Kibuka says to Selby “…you do realize…” (in reference to the white presents) where if Kibuka had said “…you need to realize…” the difference in those two words is the difference between a teenager complaining and a powerful statement being made. In Gohn’s play, we have a teenager complaining.

The one character that Gohn did get right was the white supremacist Dracey Weeks (Gareth Kelly) and to a lesser extent Hunter Weeks Kelton (Hilary Mazer.) His bombastic nature in relentlessly defending his and his kinfolk’s actions of the lynching, the stalwart position of ‘the right race’ and the vocal explosions that erupt from Kelly as he delivers these harrowing truths (that still exist in the minds of too many today) are shocking and revolting. They’re difficult to watch and they should be. The wording here is very specific, the delivery is very sharp and intensely executed, and you feel like you need a shower to get clean from all the vitriol the Dracey Weeks character is spouting. Mazer’s Hunter Weeks Kelton is of a similar caliber, though given far less dialogue to work with. Mazer does, however, master the notion of being a southern lady of an age and of money. She makes haughty eyerolls and gruesome facial expressions to express her displeasure at the ‘progressive opinions’ of ‘the white girl from the north.’ The fact that your waffling-change-of-heart white character, your whiny, wet-mop, white freedom-fighter character, and the two black characters in this production fall apart as static and generally one-dimensional in their textual creation… and the two southern white-supremacist characters are so thoroughly well-written… that certainly makes a statement, and I’m not entirely sure it is a statement that speaks the way the playwright thinks it does.

Given the flaws in the script and the pacing of the show as a whole, (rushed scenic transitions but meandering dialogue exchanges) the actors were presented with a difficult challenge. Pierre Walters and Ja’Kai Viera, despite having subpar characters to work with, do astonishing jobs on the stage. You get the ‘young teen attitude’ from Viera’s Kibuka, even if nothing that comes out of that character’s mouth is how a 14-year-old would have spoken in the late 70’s. The brilliance of Pierre Walters’ moments on stage are in his facial expressions and his moments of choosing silence. While Walters’ character of Alex does have quite a few moments where he blasts out his frustrations (which start at ten but have nowhere to escalate to), there are several striking and profoundly beautiful moments where he absorbs what he’s hearing and chooses silence and physical expression that read strongly to the audience. His generalized command of presence on stage is also impressive and guides several of the scenes that otherwise feel as if they’re falling off track.

The potential for what this play could have been is what’s most frustrating; Gohn had an opportunity to address a profound topic that is still, unfortunately, very relevant today but it just doesn’t land with the strength, reverence, and overall profundity that he thinks it does.

Running Time: 2 hours and 35 minutes with one intermission

What Was Done, a co-production between the Baltimore Playwrights Festival and Spotlighters Theatre, plays through July 23rd 2023 at The Audrey Herman Spotlighters Theatre— 817 Saint Paul Street, Baltimore MD. For tickets call the box office at (410) 752-1225 or purchase them online.