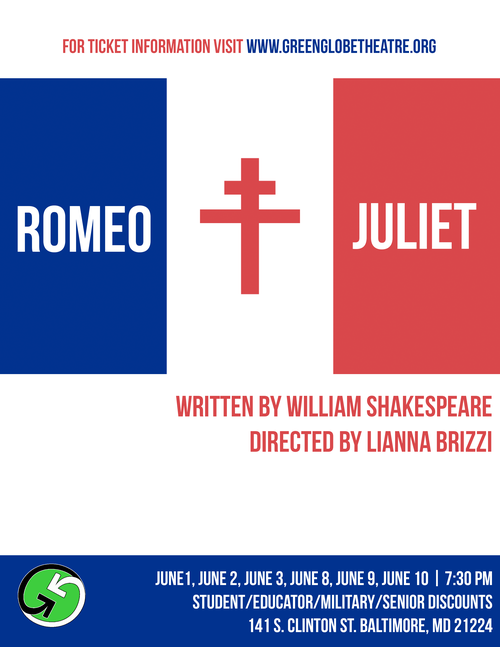

Now, thou art what thou art, a production of Romeo and Juliet. Though this production, at The Green Globe Theatre (Baltimore’s only producing eco-friendly theatre) is beyond the simple notion of star-crossed lovers meeting in fair Verona. Of course, one must be full well in all five wits to endure the length of this production, but tis worth the patience and endurance for the cinematic elements and uniquely conceived approach to placing the star-crossed lover’s tragedy in WWII Nazi occupied France circa 1944. Directed by Lianna Brizzi, this production of the Bard’s romantic tragedy ties up nearly four hour’s traffic upon the stage, but despite the pacing and length of the show is an incredible and unique theatrical experience well worth exploring.

Lianna Brizzi has shifted Romeo and Juliet out of Elizabethan Verona and pulled it forward into Nazi occupied France in 1944. The word that best describes her approach to the play, both aesthetically and conceptually is cinematic. Opening the production with projected footage of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis on the march to tin-typed recordings in old-fashioned news bulletin style, the story is swiftly transported and the war between two households is given a sinister meaning. The Capulets become the Germans, the Montagues becomes the French, with Friar Lawrence leading an underground resistance against the Nazi invasion. All of this is tied flawlessly into the aesthetic by way of Costume Designer Nicki Seibert and Set Designer Hayden Muller. With enormous banners of the Third Reich bearing the swastika across the back of one side of the tennis-court style stage layout and a stone turreted wall serving as Juliet’s balcony across the other, the scene is unmistakably set in the throes of WWII. Muller even sets four posts in the center of the stage, stringing between them faerie lights of Paris that would represent a gayer time in the city’s history.

Seibert echoes the worn-torn visualization in her sartorial selection, making crisp beige uniforms with the iconic swastika armband for the Capulets and Germans on the move, while painting the French as proper citizens in the dapper threads. Seibert’s wardrobe selections for Juliet are simple and common yet perfect for her character, especially the navy and white affair for the wedding scene in Friar Lawrence’s cell. All of Siebert’s designs, as well as Muller’s set are pulled into a living color of sorts by Lighting Designer Glen Haupt. Animating Brizzi’s cinematic vision for the show— by pulling moments of flashback, memory, and recall in and out of focus with his various illumination techniques— Haupt makes a cohesive viewing experience of the performance as these moments blossom and flourish around Shakespeare’s original text.

Herein lies the rub and the show’s major issue. Brizzi has created an entire secondary story that is layered atop of and woven throughout Shakespeare’s original. Her conception is striking; there is powerful imagery, moments of subtext made readily visual, and simply put it is a thing of grace and beauty. However, in doing so, Brizzi has created some unnecessary length to the production, which in itself wouldn’t be an issue if the overall pacing of scenes were tighter, more thorough editing had been done to the text, and various members of the cast were encourage more firmly to speak quickly in meter. Brizzi constructs jarring moments that could easily replace sections of text because they are that evocative. The one that comes immediately to mind is the slow-motion undressing and redressing that Juliet does to the old record playing (a callback to earlier in the play when Romeo romanced her in the bedroom with the same record) just before drinking the mock poison. This scene plays out beautifully, but then is followed by all of her text when it could have been easily replaced by allowing this silent visual to stand in its stead and would have created a more powerful impact that presenting the scene first and the text after.

Brizzi has other such moments, ones that are fabricated specifically to show character development that Shakespeare left implied or unmentioned entirely; they revolve primarily around Tybalt. He’s seen interacting playfully with Juliet, giving her a German switchblade knife; he’s seen helping Lady Capulet with her gown and being quite familiar with her while she’s dressing for the dinner-ball scene (which plays into the abusive-husband dynamic that is explored by Lord Capulet.) These moments are hearty and rich with characterizations that are otherwise underplayed and ignored in traditional stagings of Romeo and Juliet. Further still does Brizzi ground her concept in the reality of World War II; the Nazis pacing through the orchard and shining their light into Juliet’s balcony (to trigger her line “Ay, me!”) or the air raid siren with the entire cast pausing and responding at the beginning of the show; all of these moments culminate into something marvelous to behold, if the timing that their inclusion adds to the production can be forgiven.

Despite the timing and sluggish pacing, the performances— as they are presented through the lens of Brizzi’s World War II vision— are solid. Naturally, there are some more solid than others, but this often comes as a natural occurrence with most Shakespearean productions. The one thing that the cast has a consistent handle on with this performance is expression. Though there are lines that falter, due to pacing, natural accents, or sometimes just softness of speech, what is missed in articulation or audibility is made up for in animated facial features, full body articulation of emotion, and other such expressions to convey the message and importance of the text.

L to R Bottom Row: Julie Press as Nurse, Allie Press as Juliet and Carolyn Koch as Lady Capulet Lucas Shipley

The title of the show may be Romeo and Juliet but there are others, who despite the lack of lines, make their presence known on stage. Lady Montague (Peggy Dorsey) is one such example; her death, which is often edited out of the performance— and sometimes her character entirely— is a profound moment of silence where you witness her collapse from a broken heart. (This is Romeo and Juliet, almost everybody dies, so there’s no spoiler warning here.) Tybalt (James Ruth) too, though he does have lines— that when he delivers them are bursting with furious rage— is another such character who is more developed in these enhanced wordless scenes. Ruth explores the friendly side of Tybalt both in his relation with Juliet and the Lady Capulet in the aforementioned scenes, making him far more dynamic than the boorish and brutish text that Shakespeare gives him.

Painful to behold is the dynamic in the Capulet household. With Daniel Douek and Carolyn Koch as Lord and Lady respectively, there is a clear presentment of abuse and alcoholism occurring between them. Douek is the leader of the French-invasion branch of the Nazis and his bombastic outward eruptions are proof positive that the character is right for the assignment. Playing up the violence that is inherent to such a character, it’s no wonder that Koch’s character takes to the bottle. The mismatch with this dynamic falls during the epic scene wherein Capulet threatens to cast out Juliet upon her refusal to marry the County Paris (played sweetly and with diligent exception by Jake Schwartz.) He hauls off and backhands both Lady Capulet and Juliet, his wife and daughter, but when the Nurse (Julie Press) takes a stand against him to defend the poor weeping maid, he does not strike her. This is a furious man, drunk on power and his own temper, readily striking members of his family but not the household help? It seems a directorial missed opportunity to have not gone further down this path.

Julie Press, as the nurse, though one of the primary offenders in slugabed pacing, is fascinating and exciting to behold. There is something wondrously quirky and humorous about the way she delivers the nurse, rambling on at the mouth every chance she gets, particularly when it comes to interacting with Juliet. Press does, however, have a fiery internal energy that pipes up when required— both during the aforementioned scene with the Capulets and when chasing Mercutio off in the street scene— and she presents a well-rounded portrayal of the comic relief as it were in this case.

Romeo (Tavish Forsyth) is well balanced against Juliet (Allie Press.) Forsyth takes a heartier emotional investment in the character, and more readily addresses the audience, particularly when fawning over Juliet. Directorial sway has the audience on the periphery and occasionally engaging with the performance (bring your dancing shoes!) and Forsyth takes advantage of this as his lines often lend themselves to this practice. The chemistry between them is delightful, sweet and demure is two young lovers ought to be. Press’ most impressive scene is in slowly divesting of her day garments and preparing to drink her poison; her body language and overall physical expressiveness in this moment is stunning.

The voice of calm reason and reckoning, Friar Lawrence (Terrance Flemming) is a beacon of hope and peace in this volatile production. In this conception of the show, Lawrence is leader of the underground resistance against the Nazis, which makes him not only powerful but even more holy in his pursuits of justice to help Romeo and Juliet find their fate together. Flemming is versatile, going from humorous to severe in the blink of an eye when the text calls for it. He also follows closely to the meter of the text when and where applicable. There are even tender moments shared between he and Young Romeo (played by Sam Noll, as a part of the flashback cinematic concept layered over the performance by Brizzi.) Watching the two of them bonding together in a flashback scene strengthens the meaning of his relationship with present day Romeo tenfold.

By their troth they do steal the show and run away with it in all their tomfoolery and shenanigans, this Benvolio (Jeff Miller) and this Mercutio (Dean Whit.) Miller, who is often over the top in the way he carries his character, both carrying on and carousing with Romeo and the others, is a refreshing dose of wit and wonder in this production. His fate, which is ill-abused by the director, is even more striking. He comes to Romeo, who has been imprisoned by the Nazis, only to discover he is too late; Balthazar has helped him escape (with the wrong news of Juliet’s death) and in a striking moment with an air-raid siren, Nazis and their guns, Miller expresses the sheer terror of any mistaken man walking among Nazis in the war.

Whit, as the marvelous Mercutio, possesses a finesse that just flows off of him, every step, every word, every gesture. It’s difficult to put such a quality into words as it is not so ostentatious as to be called flare but not subtle enough to be called a quirk or affectation. Whit plays Mercutio as if he were a Cheshire Cat, sly and unctuous yet of good nature and good humor with a hint of bravado that might just make him mad. Every time he strolls into a scene, the audience snaps their eyes to him; a most wondrous player indeed with everything from his Queen Mab speech to his Pox upon both their houses being absolutely divine.

There is music to entice the ear, and visuals to appease the eyes; there is a story tangled up in the lengthy traffic of the stage. It is one worth enduring, but come with patience as it is a bit longer than your average Romeo and Juliet.

Running Time: Approximately 3 hours and 30 minutes with one intermission

Romeo and Juliet plays through June 10, 2017 at The Green Globe Theatre in residence at Breath of God Lutheran Church— 141 S. Clinton Street in the heart of Highlandtown of Baltimore, MD. For tickets call (443) 963-9704 or purchase them online.