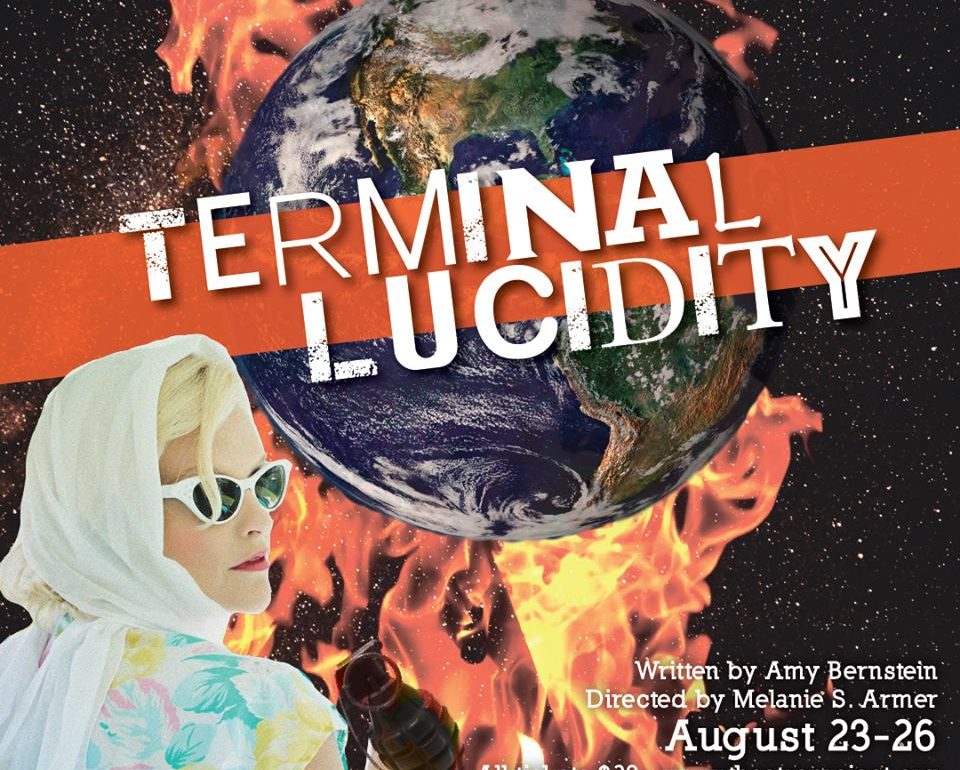

Dada comes to Baltimore in the raw and intimate experience that is the world premiere of Terminal Lucidity, written by Amy Bernstein and directed by Melanie S. Armer. This work, presented by Baltimore’s own Theatre Project, brings to the stage a look at the dark and damaging political path America may currently be treading through the experiences of the women affected by the “monster in her midst.”

Dada in and of itself means… nothing. There is no deeper meaning to the word. No hidden subtext to the choice of the word; and that in essence is the entire point. The beauty of the Dada movement lies in its ability to break away from the conventional to serve as a conduit for an audience to experience a message that is more anti-art than art, yet juxtaposed with an overarching message that addresses some deeper observations of the world around us in a sense of disillusionment. And that is just what Theatre Project’s Terminal Lucidity aims to accomplish. Bernstein executes this wonderfully by interweaving the overarching effect the “monster” has on the women represented in the piece, by connecting their experiences with one another through both a support group setting and a series of one-on-one conversations that flow fluidly from one into another to show the inevitable connection these women have as a whole.

The show begins with the audience. Patrons are not able to enter the theatre until just before the production’s start, and are invited, rather than directed, to take a seat in the circle of chairs surrounding the play-area. Meant as a way to further endear the audience to a sense of intimacy, audience members are greeted at the door and offered coffee and donuts once inside. Once the production begins, for one brief moment, the audience is whisked away to a circus. A woman, dressed in a whimsical black and white ensemble guides the attention of the crowd, while another woman performs on the silks hanging from the ceiling. The woman in black and white, credited as the Spritely Baroness, draws the crowd’s attention as she begins to recite the Standard Phonetic Alphabet. This piece, in its own way, leads the audience into the world of the absurd gently as the Baroness begins reciting the Phonetic Alphabet as we know it, and seamlessly glides into reciting alpha-phonetic-gibberish, thus transitioning the audience now into the world of the absurd.

The next movement further immerses the audience by revealing that the layout of the chairs surrounding the space is meant to represent a support meeting, which the audience feels a part of. From this point onwards we are introduced to the women’s characters, not by their names for they have only identities, and the raw basis of their experience with “the monster.” One of the strongest aspects of this production is the women’s lack of names, but strong identities. By not naming the characters, they are instead better able to broadly encompass the broad spectrum of women and their experiences while simultaneously exploring a singular series of effects these women experience because of the unnamed, though thinly-veiled, monster.

The way the “monster” is referred to throughout the production could be perceived to represent one single individual (and spoil alert: it’s Donald Trump), or a metaphor for many. This then begs the question as to whether the alluded to “monster” only represents one single entity, or if it is broad enough to represent a commonality among many. That is to say, there was never a sense of “all men” being represented by the “monster,” but there was a poignant theme of, “yes, all women” are affected by these “monsters.”

For the majority of the production’s runtime, the players are dressed conventionally to the style which conveys their character’s identity. Costume Designer Deana Fisher Brill, executes this wonderfully as each character’s costume adequately conveys the type of woman each character exudes as they share their experiences. Dressed in contemporary clothing, the players sharing in the support circle at first glance appear to be any everyday woman, but after a few words, it becomes abundantly clear what type of woman each player represents, and their choice in clothing compliments their identity perfectly. The ending costume change for the ensemble into simple black t-shirts with their identities written on name tags only further drives home the notion that these women on stage are far more about representing their identities in society than their singular personal (named) identity.

In case you were ever to forget that this world you have entered is Dada, Sound Designer Glenn Ricci is there to remind you. The sounds and music Ricci uses do well to tie into the sense of melody and chaos abundant in the action within the circle. At one moment early in the support circle portion of the play, the music played is jumbled and chaotic, while the sounds the actors make while moving and shifting their chairs becomes almost melodic in its juxtaposition. While the audio and sound used throughout the course of the production is well-themed and placed, the sound levels in the first half detract from the words spoken on stage. While the levels did seem to be reduced as the evening went on, the sounds played over spoken lines in the first half made it difficult to understand what the actors were saying. Since all but one of the players do not use microphones, there are times when the volumes of the sounds overwhelm the actors, making it occasionally impossible to understand what they are saying. However, this did seem to correct itself as the production carried on, and thus better complimented the actors rather than dwarf them.

The only real critique of the performance pertains to the occasional loss of projection. At one point or another, almost every performer was guilty of becoming too comfortable in the intimate space. When this occurred, the performer would speak on a more conversational level rather than at a volume in which the entire audience did not need to strain to hear.

But, other than this cross from performance into conversation, the entire ensemble does a marvelous job at performing both as a chaotic unit and displaced single entity. Each character has an opportunity to shine. Naturally, the character of the Spritely Baroness, played by Vivian Allvin, has the most opportunity to steal the show with her natural charisma and wit. She effortlessly flounces around the play-area, interjecting quips or sounds as she leads the transitions from one “scene” into another.

Several of the more complex characters were those of the Old Woman, Senator, and Wife/Mistress, played by Autumn Weisz, Elizabeth Stuelke, and Ankur Garg respectively. These women’s identities are complex and multifaceted due to their positions of being both immediately tied to the “monster” through some physical or political tie, and being women. The Old Woman feels disgust for she gave birth to the “monster,” the Senator helped him rise to power, but that’s just politics as usual, and the Wife is torn because she feels she must stand by his side as his wife, but sympathizes with the women through her personal past victimizations. Both Jedia Greene, the Raped Girl, and Julie Jordan, the Offspring, give grounded and identifiable performances, and will surely be names to watch for as they continue their careers on the stage.

Director Melanie S. Armer and Playwright Amy Bernstein keep the pace of the production on pointe for the majority of the piece. As one action flows effortlessly from one into another, in its own chaotic way, the production seems to be over as quickly as it began. The only period which dragged the pacing was the final leg of the production in which the cast builds the wall/ cages/ building. While this serves as a dramatic and effective visual to encompass the symbolism of the wall which serves as a physical barrier to further ostracize the women debased, humiliated, and degraded by the “monster” and society as a side-effect, the physical act of building it slowly piece-by-piece, woman by woman, stops the otherwise captivating performance pacing. Yet, it is worth saying that the piece describing the detriment to which these physical and symbolic symbols serve in crushing and burying women and erasing their experiences from societal sympathetic consciousness, does serve as a powerful statement to end the production.

As with any sort of avant garde theatre, if you enter trying to comprehend every thing as it occurs, you will wear yourself out. With Dada, it is only when you allow yourself to give up understanding and allow yourself to experience the words, images, and sounds that you can begin to grasp the message as it flows through you. As Dada was born in a time where there was growing concern of the rise of fascism, Terminal Lucidity certainly makes for a very timely message.

Running Time: 60 minutes with no intermission

Terminal Lucidity plays a limited run through Sunday August 26, 2018 at Baltimore Theatre Project— 45 W. Preston Street in the Mt. Vernon neighborhood of Baltimore, MD. For tickets call the box office or purchase them online.